Batch Processing with FluCoMa

Batch processing corpora with the Fluid Corpus Manipulation toolkit.

If you want to go straight to the code examples, they can be found under Batch Processing Code Examples.

Introduction

When working with machine learning and machine listening, we often need to process and work on collections of sounds, slices or analyses together or as batches. “Batch processing” is actually quite familiar to musicians although it is often not referred to by the same name. An example would be if you have ever normalised a bundle of audio files, or if you have ever rendered a multi-track session in the DAW. In any of these cases, the computer works on a collection of things together. When we learn how to manage and program batch processes, it can be a powerful tool for manipulating large corpora and for working with collections of musical resources.

Batch Processing Code Examples

This section will demonstrate with code examples a number of ways in which batch processing can be implemented in Max, SuperCollider and Pure Data with the FluCoMa toolkit and show how our interfaces can interlock with the existing ones in your creative coding environment (CCE) of choice. The explanation of particular objects and processes will be in the patches and scripts themselves.

Analysis of Segments

In this example a single audio file is sliced into a collection of segments. Each segment will be analysed with an audio descriptor and the result for that segment will be stored in a DataSet. The example illustrates how one can iterate through several portions of the source buffer and use the segmentation result to control a process that only analyses specific portions of time in the source file.

The step-by-step workflow is as follows:

- Segment a sound into small chunks.

- Analyse each chunk using an audio descriptor.

- Calculate the average of that audio descriptor for each chunk.

- Store the average for each chunk in a DataSet.

Decomposing Multiple Files

In this example a collection of audio files are processed as a batch using the HPSS algorithm. Each decomposition is output so that the results can be accessed later for audition or storage on disk. The example illustrates how a corpus might be processed as a whole in an automated way.

The step-by-step workflow is as follows:

- Create a corpus of multiple audio files

- Decompose each audio file into harmonic and percussive complnents using HPSS.

- Store the results in some sort of container. This will depend on the CCE.

Non-Blocking Processing

In the two examples above you may have noticed that whenever these intensive batch processes are started it has the potential to freeze or hang Max and Pure Data. SuperCollider doesn’t suffer the exact same issue because the language will continue to function even while the server is processing. However, it is easier to get into trouble in SuperCollider by launching lots of threads and potentially jamming up the server. To work around these limitations, FluCoMa objects can operate in their own threads that can run in parallel to other processes. This is sometimes referred to as asynchronous or non-blocking programming.

The benefit of making one’s code asynchronous is that processes can be triggered and won’t block or be blocked by something else. This is a massive boon in a number of scenarios, albeit at the introduction of complexity in how we might expect processes to start, finish and interact with each other. In any CCE, creating threads isn’t a simple gateway to faster batch processing: once you add too many, then the scheduling overhead starts to kill performance. This is particularly prevalent when the situation is characterised by many small jobs. In situations like these it can be more expensive to spawn a new thread to do the processing, rather than just getting on with the processing synchronously.

The examples above illustrate how using process() and wait in SuperCollider and @blocking 0 and -blocking 0 in Pure Data can allow us to trigger processes and await the results of those processes.

Discussion

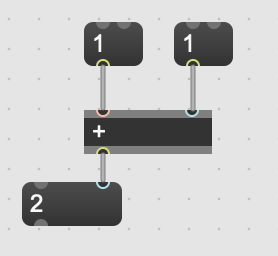

Without even addressing FluCoMa objects directly, it is relevant to remind ourselves of what forms batch processing already exists in Max, Pure Data and SuperCollider. Let’s first take a look at the humble Max list and how it is useful. We’ll start by making a small patch that adds two numbers together.

This is fine. However, it is limited to adding two singular values together. If we want to use it to add two collections of numbers together, we would have to stream the values of two lists into the inlets, get the result and construct it back into a list. Another approach would be to copy this bit of patch multiple times and serve each copy with two single values (scalars).

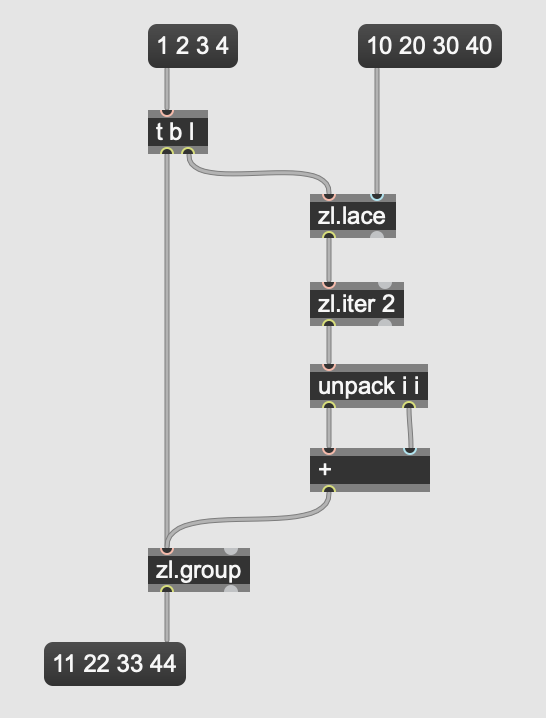

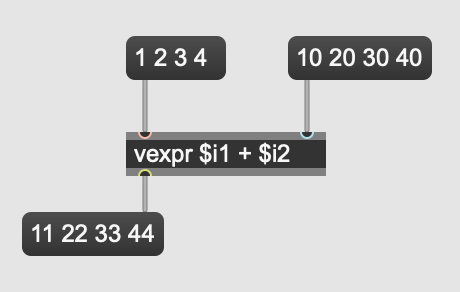

We can avoid these kinds of workflows by instead using objects that deal with collections of items in a list natively.

The complexity of the patching hasn’t increased greatly, and by replacing + with vexpr (vector expression), we can process entire lists of values. The patch will also still work with single value inputs (scalars) making it much more flexible than what we had originally. While the patching itself is not too complicated, knowing about the existence of these objects and how they work is not greatly emphasised in the way visual programming is taught, which is often concerned entirely with streams of scalar values. Furthermore, while this is just a toy example, it demonstrates that the notion of processing groups of things together is not the first and most obvious way to patch. Conversely, SuperCollider has the language (sclang) which offers built-in methods for dealing with arrays of data. Most operators are also overloaded, meaning the interface for adding two integers is roughly the same as adding two arrays of integers. For example:

(

// Add together two integers

z = 1;

x = 10;

(z + x).postln;

)

(

// Add together two lists

z = [1, 2, 3, 4];

x = [10, 20, 30, 40];

(z + x).postln;

)In other words, each CCE has a set of idioms and paths of least resistance that may or may not lend themselves to batch processing. We hope this article helps you to overcome these when using the FluCoMa toolkit, as well as open up your wider knowledge in your CCE of choice.