Audio Decomposition using BufNMF

Decompose an audio buffer into component parts using non-negative matrix factorisation.

Decomposition

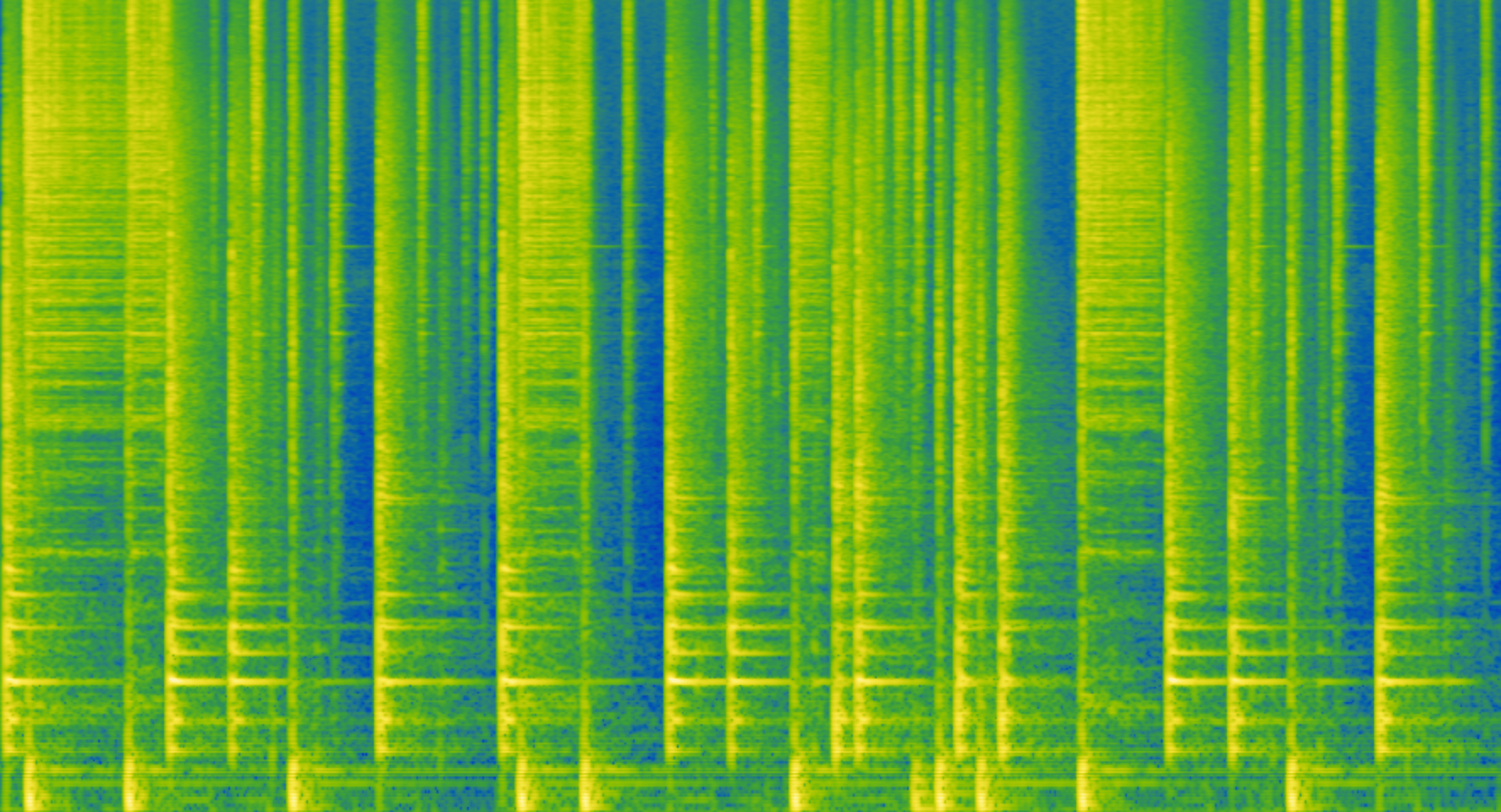

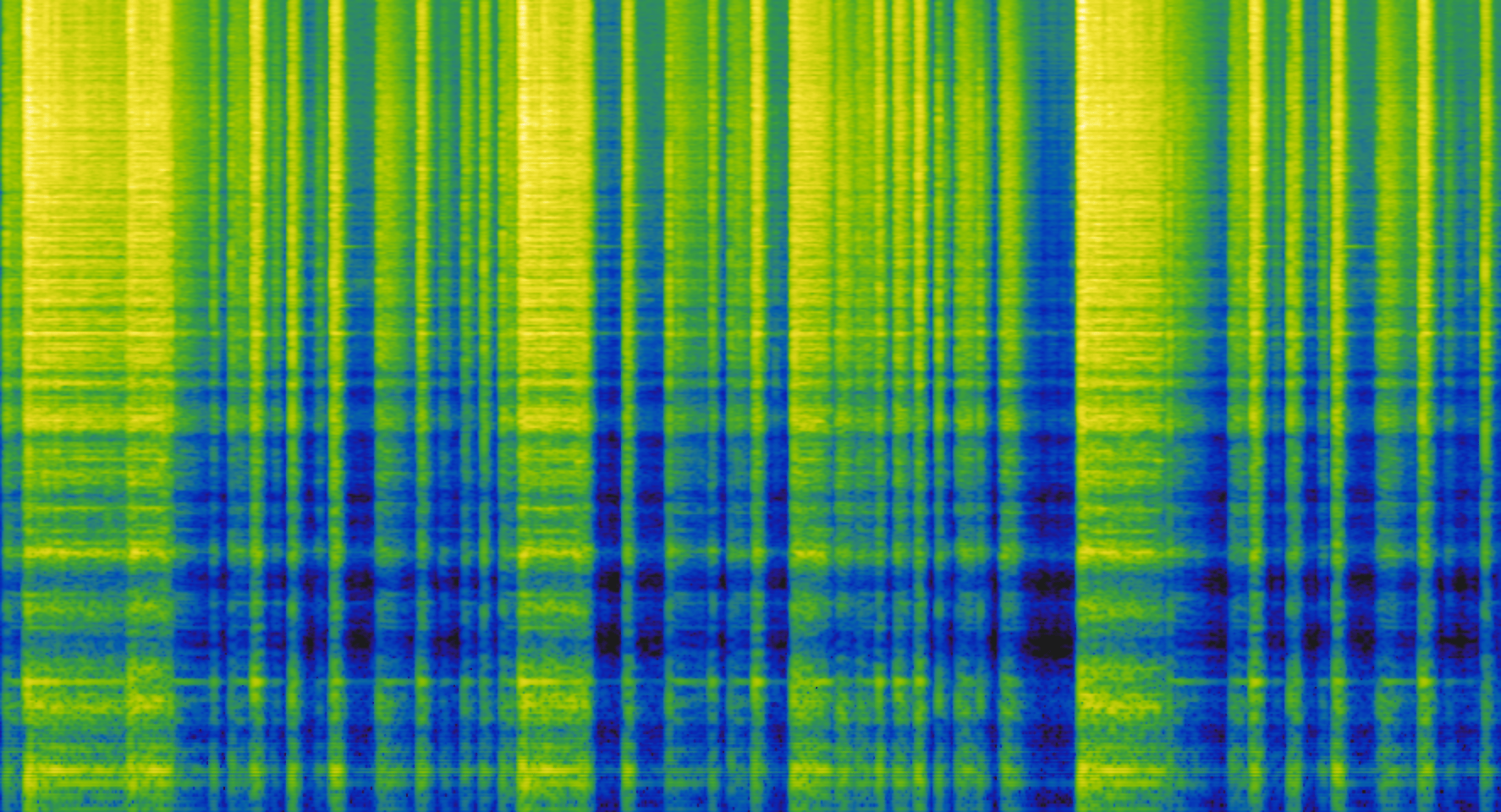

“NMF” stands for Non-negative Matrix Factorisation, which is a machine learning algorithm that can be used for decomposing an audio buffer into component parts. In this example, we’ll look at decomposing a mono drum loop into three different mono audio buffers, each hopefully containing the hits from just one of the instruments: kick, snare, and cymbal. Here is the recording and spectrogram of our drum loop.

Mel-frequecy spectrogram of drum loop

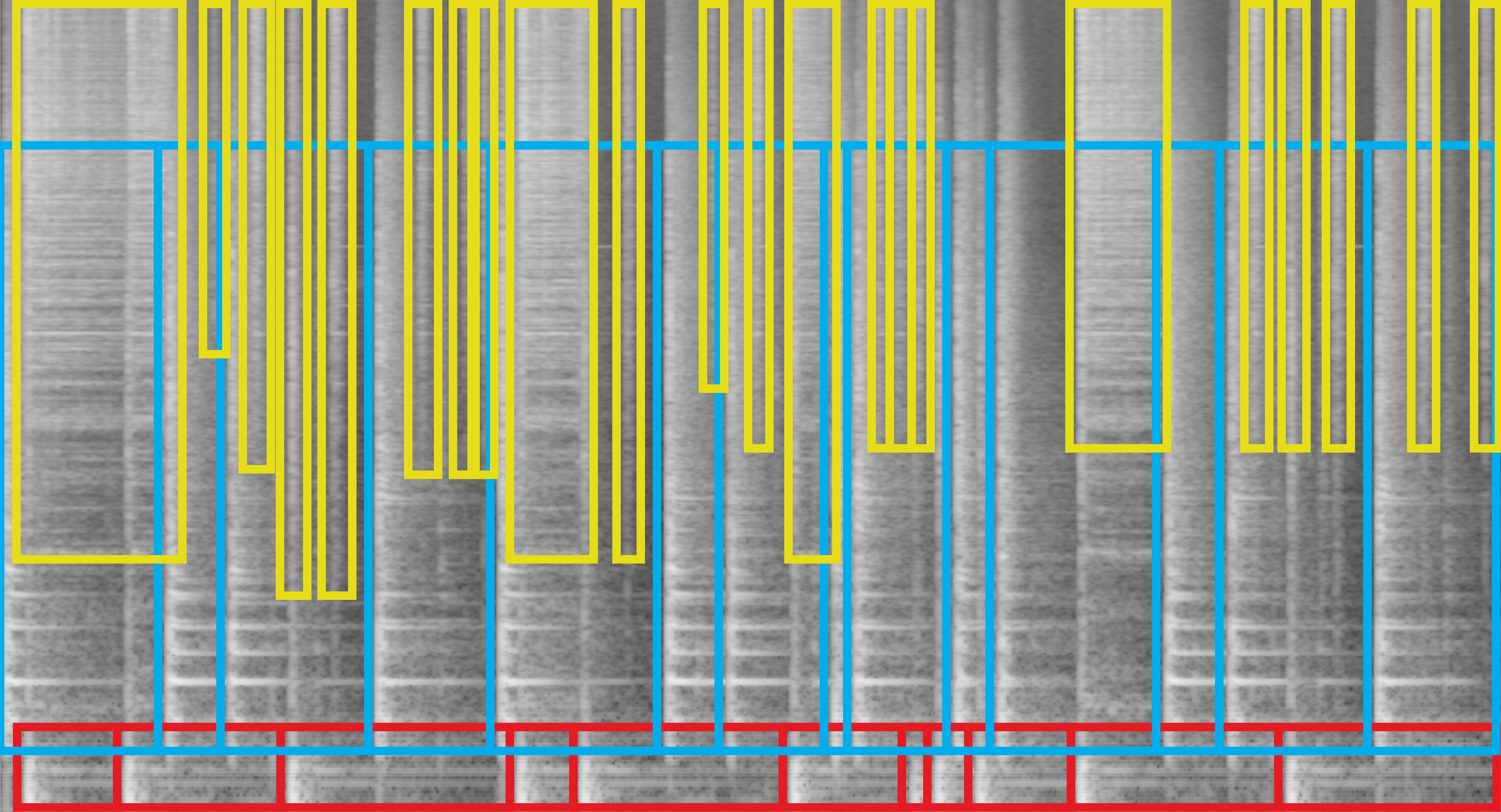

The spectrogram below roughly identifies where in time and frequency each of these instruments are present.

(red = kick, blue = snare, yellow = cymbal)

As you can see (and hear in the playback), these different drum hits overlap quite a lot in both time and spectrum meaning that a purely time-based (such as a slicer) or purely spectral (such as a filter) strategy for separating these hits wouldn’t work very well.

This is where non-negative matrix factorisation can be quite useful.

We can use BufNMF to analyze the drum loop’s spectrogram and determine which parts of the spectrum always (or often) occur together in time. For example, in the snare hits (the blue boxes) you can see the different partials of the drum head’s resonant tone (the horizontal bands from ~300 Hz to ~2000 Hz) always occurring together. Sometimes there is also some cymbal sound happening (above that in a yellow box), but because the cymbal sound is often not there, NMF will try to decompose the spectrogram in such a way that these can be considered separate components. In general, the more that different sound objects are separated out in time and the more repetitions of each sound object, the better BufNMF will be at identifying and separating them.

Processing this mono drum loop with BufNMF (specifying that we want it to try to decompose the sound into three components) returns these three buffers, one with each component it was able to separate:

SuperCollider Example Max ExampleComponent 1 (contains mostly just the kick drum hits)

Mel-frequency spectrogram of Component 1

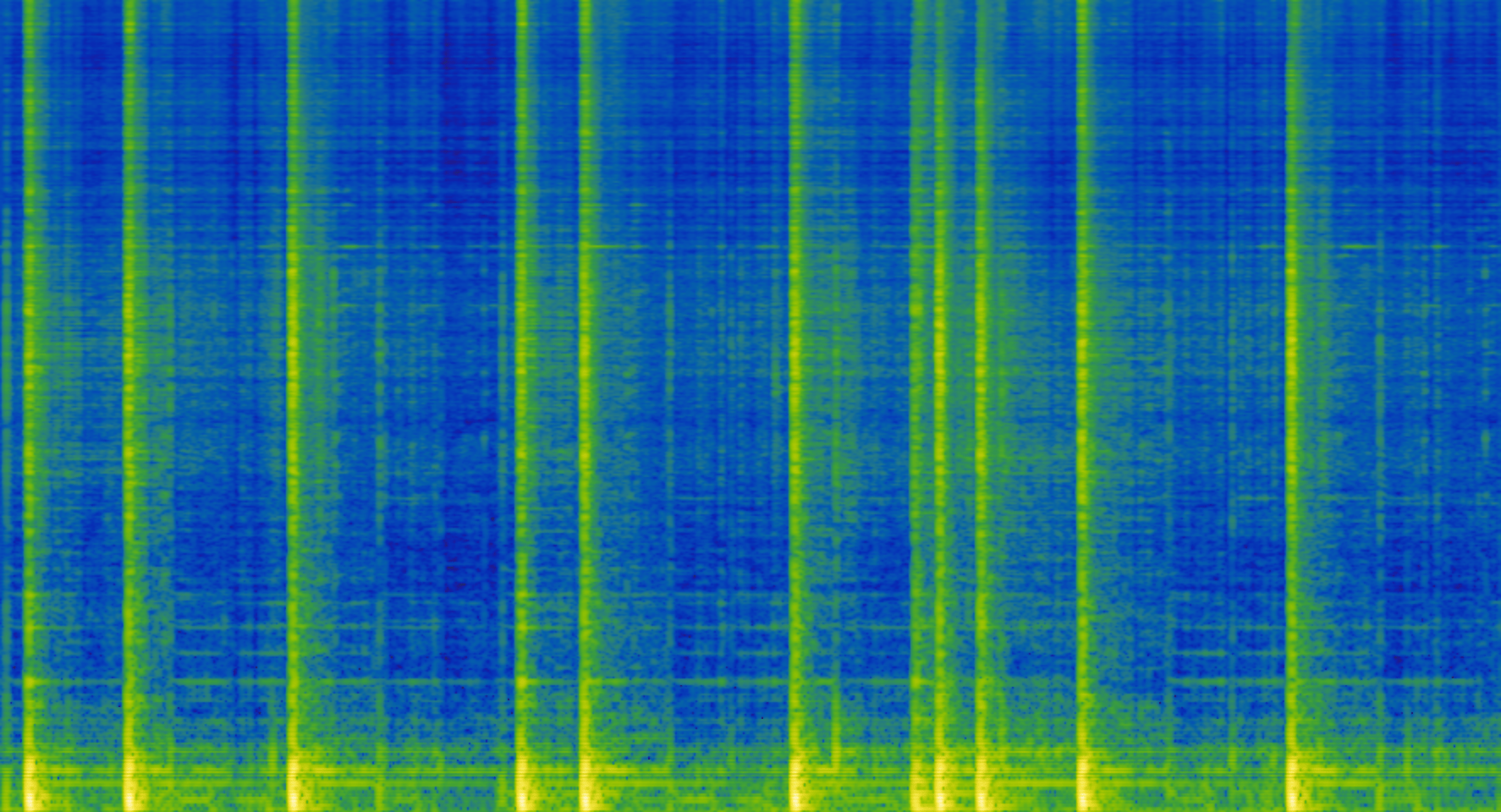

Component 2 (contains mostly just the snare drum hits)

Mel-frequency spectrogram of Component 2

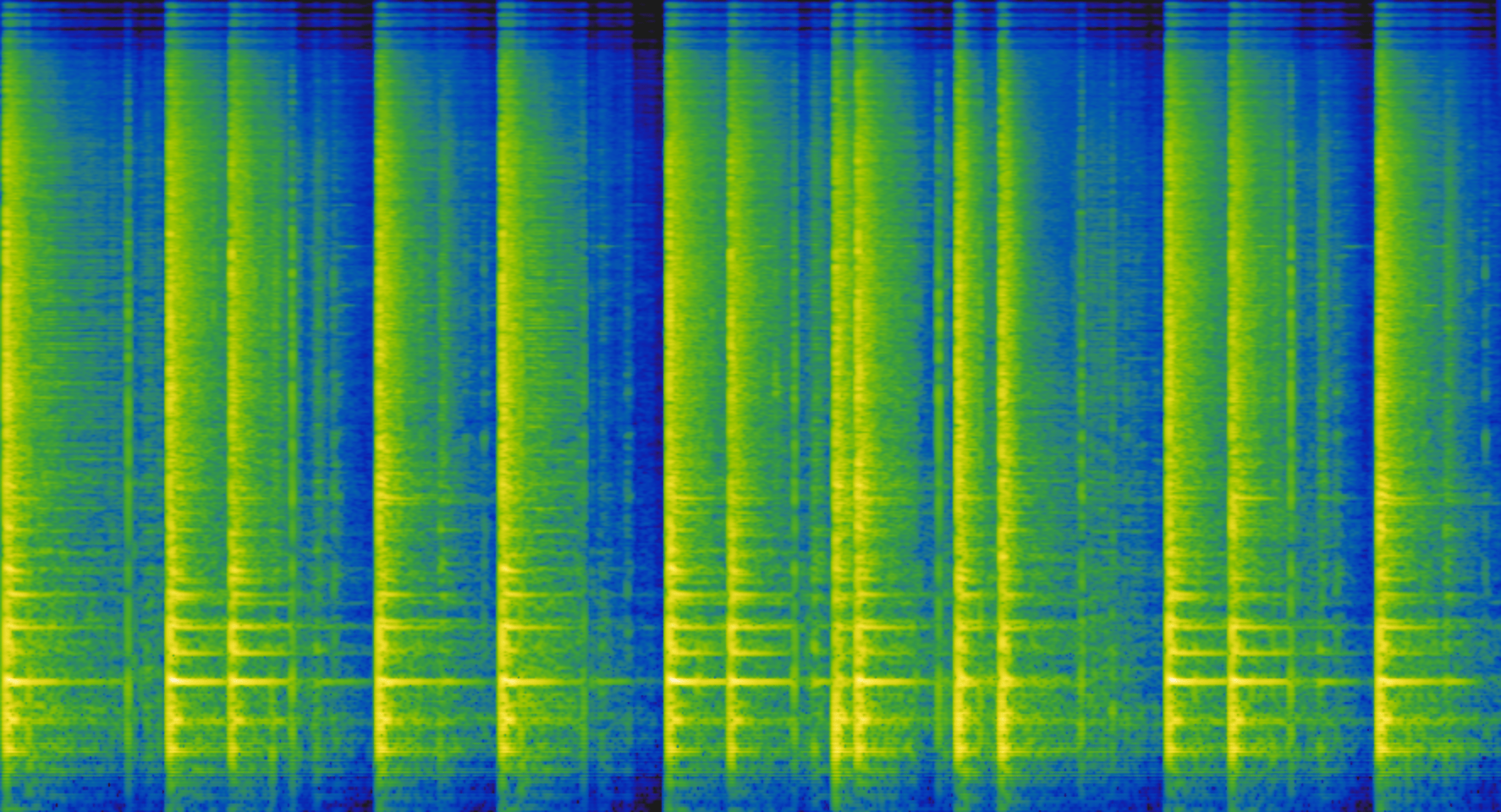

Component 3 (contains mostly just the hi-hat hits)

Mel-frequency spectrogram of Component 3

In this case, BufNMF has worked quite well! It separated the sound into three components that strongly resemble how we as humans may have separated them in our minds while listening. This won’t always be the case. BufNMF knows nothing about how we perceive separate sound sources, such as these different percussion instruments. The rest of this explanation will continue to refer to the “hi-hat component”, “snare component”, and “kick component”, for convenience because this analysis turned out this way, however, different audio buffers won’t be able to separate as clearly as this one.

A quick experiment to test this would be to decompose the same drum loop while specifying only two components and see what happens. Specify four components and try to guess what the output will be. How does your prediction match with what BufNMF provided?

Also note that the order of the components may be different every time (if you’re coding along, yours are probably different right now). This is because BufNMF begins its process from a randomized state so the resulting components will be in a randomized order each time it is run.

The initial randomization in the algorithm also means that the components themselves won’t always be exactly the same: the “snare component” (whichever order it is in) might be slightly different from result to result and likewise with the other components. Often they’re quite similar, even indistinguishable, but if you don’t like the output of one BufNMF processing, try it again and see what you get, it may be different!

Bases and Activations

BufNMF gives you access to the “bases” and “activations” that it derives from the analysis of the spectrogram.

Bases

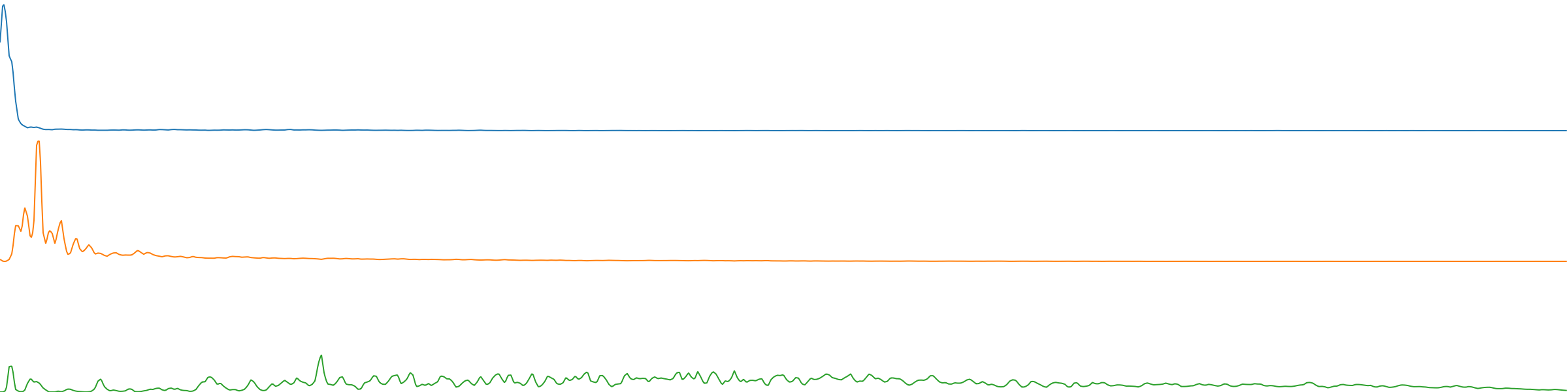

The “bases” can be thought of as spectral templates (or filter curves) that BufNMF discovers in the course of analyzing the spectrogram. As described above, BufNMF analyzes a spectrogram to determine which parts of the spectrum always (or often) occur together in time. These parts of the spectrum that occur together are then combined into one spectral template (or “basis”). You can see below the bases for the drum analysis conducted above. Each plot is a spectrum (the x axis is spectral bins, representing frequency, and the y axis is magnitude, representing loudness).

(blue = kick, orange = snare, green = hi-hat)

Basis 1 only has one peak of energy very low in the spectrum representing the kick drum. Basis 2 has the various partials of the snare drum head’s resonant frequency. Basis 3 has lots of energy higher in the spectrum, representing the hi-hat sound. (See NMFFilter for how these bases can be used to filter a sound signal through these spectra.)

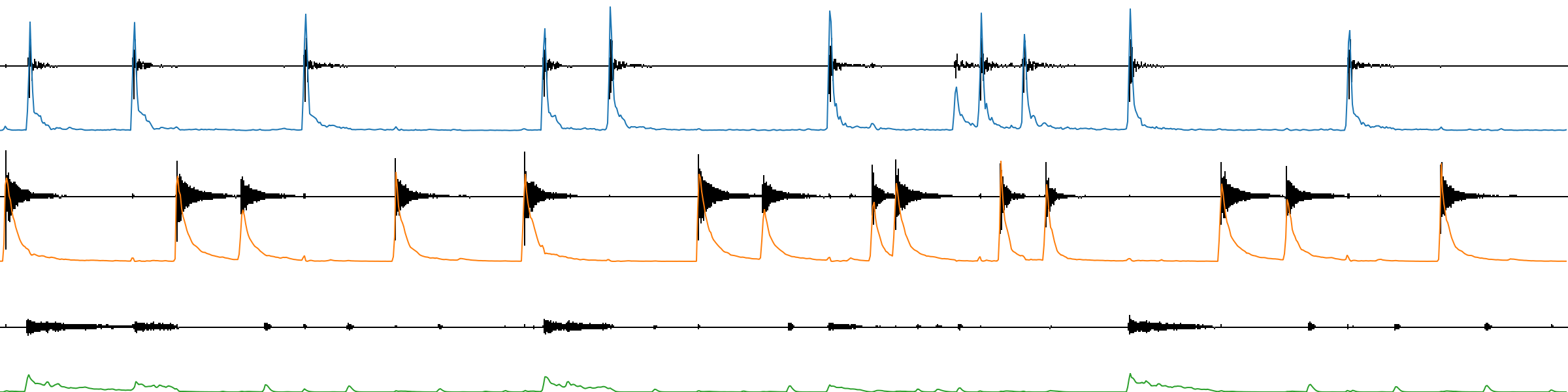

Activations

Each base is also paired with an “activation” which represents how present each of these bases is throughout the audio buffer (through time). Below you can see the activations from the drum analysis conducted above overlaid on the waveforms of their corresponding components. For each plot the x axis is time and the y axis is loudness.

(blue = kick, orange = snare, green = hi-hat)

As you can see, each of these looks like an envelope follower for the drum instrument component they represent. These activations could be used to control the loudness of a signal through time. Here is an example of each of these activations modulating the loudness of pink noise.

When BufNMF decomposes the mono drum buffer into the three component buffers (as seen and heard above) it does this by combining each component’s basis with just that component’s activation to resynthesize the component’s resulting audio buffer. For example BufNMF combines just the “hi-hat basis” (i.e., spectral template) with just the “hi-hat activation” (loudness envelope through time) to resynthesize the resulting “hi-hat component” audio buffer. This usage is not dissimilar to a vocoder, where, instead of bandpass filters, finely-tuned spectral contours are optimised through machine learning.

There are a suite of objects in the FluCoMa toolkit that can be used along with BufNMF’s bases and activations. Check out NMFFilter, NMFMatch, NMFMorph, and BufNMFCross.