Dealing with Time

Strategies for encoding and explaining time to a computer.

Introduction

When we analyse sound with computers, capturing how things change through time is of critical concern. For humans, listening is an incredibly complex process that bundles many physiological and psychological elements into a relatively passive and automatic process. We can identify different perceptual features of sound simultaneously, understand intentions behind its production, trace musical elements that evolve and come to interpretations that connect different listening experiences together. Computer’s have no such understanding of sound and by comparison are really quite stupid when you compare them to what a human can do. However, computers are especially good at quantitative listening, and generating numbers that may or may not faithfully express the perceptual characteristics of sound. You might be thinking, “Hey! You just described an audio descriptor”, and you would be right. This set of learn articles is going to reflect on the tension between human and machine listening and how that affects the way we encode musical representation, specifically time in data using audio descriptors and other forms of data.

Time, Evolution and Data

Sound evolving and being experienced through time is an inescapable facet of how we listen to and interpret it. Think about all the different ways that a sound may or may not vary and how this contributes so strongly to its nature, ability to elicit different responses as a listener. One neat entry point is to start to describe sound with curves and shapes. If you wanted to dive into a more theoretical approach to this way of thinking, then you might want to read about Temporal Semiotic Units.

Click the play button and listen to the sound. The green line moving up and down over time maps onto the changes in amplitude or loudness.

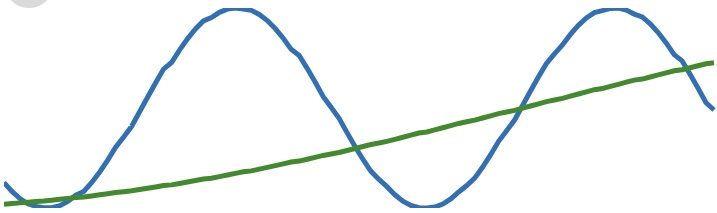

We could also describe other aspects like pitch, here described by the blue line.

The combination of many different curves that trace perceptual elements of a sound over time might culminate in a more holistic understanding of a sound. This is still quite simple, but imagine the amplitude and pitch moving together as a kind of multivariate audio descriptor. Let’s imagine amplitude and pitch moving together now with the green and blue lines depicting amplitude and pitch respectively.

These “shapes,” though simplistic, could form the basis for analysis or serve as intrinsically useful structures for mapping or other musical applications. However, human listening is rarely so straightforward or uniform. We combine, layer, and meld multiple shapes simultaneously across different time scales, observing small changes in the moment while considering the broader context.

If we listened to the same oscillating pattern for 20 minutes, would we still perceive variations in pitch or amplitude as meaningful changes? Considering these aspects reveals the challenges of encoding sound’s evolving nature into data. How much time is “enough” to be meaningful? Is all time equal in every musical and machine listening scenario? How do different time segments relate to one another?

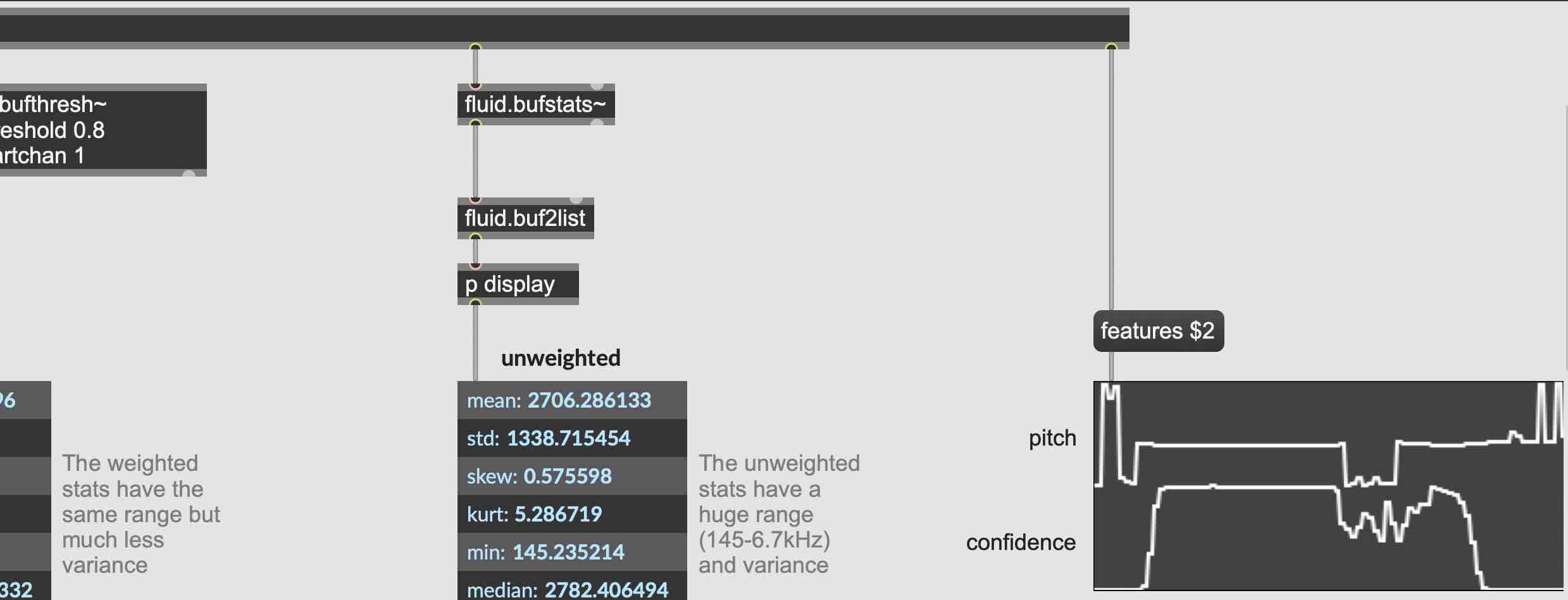

This question emerges in several different places, especially in our own tutorials and ultimately we think it is important to recognise that machine listening is context specific. For example, the classification with a neural network tutorial deals with time in a straightforward and effective way. A representation of different timbres is constructed by capturing and storing several examples of very brief moments in time using the MFCC descriptor. This analysis procedure is designed with somewhat static sounds in mind, where the variation of those MFCC values will be relatively stable and won’t evolve too rapidly. The neural network that learns from this data is also quite clever. In theory, with enough examples and sufficient training the network can be good at differentiating timbres with just these instantaneous snapshots of sound data provided to it. For example though, if you wanted to explicitly have the same neural network classify sounds based on the evolution of timbre, you would probably want to explore a different method of capturing the temporal features of those sounds, rather than just looking at singular spectral frames of analysis.

As another example, the 2D Corpus Explorer tutorial operates on a set of basic assumptions about how time might be encoded into data. Like the classification tutorial, it uses MFCC data alongside statistical derivatives to try and encode the evolving spectral structures of short sound samples. This approach is actually quite prone to producing noisy and nonsensical data so we slap another algorithm on after that called UMAP, and hope that it can unfurl some structure from that mess of data it’s given. The idea is that after UMAP has analysed and compressed the data it was given, a new set of fewer numbers will emerge that have some kind of statistical relevance and were able to introspect on the time varying aspects of the sounds encoded in those statistical derivatives. This approach, and the classification tutorial’s approach are of course entirely validated by their success in musical practice. They are by no means perfect approaches to encoding time and we are not looking for exact answers here, rather, they are functional patches based on a context-specific musical application.

This is really just the start of thinking about time and we hope that you delve into it more through a series of Learn Articles that we think might provoke you to consider how you represent time through data, and how the evolution of sound can be captured and encoded into workflows with the FluCoMa toolkit.