NMF Piano Tracker for Symbolic Audio Effects

In this article, we’ll take a look at some of the work that Hans Tutschku did using the FluCoMa tools, notably the conception of a piano tracker that uses NMF and how this allows him to perform symbolic operations on audio.

Hans Tutschku

Introduction

Download the demonstration patches for this article here.

Today we’ll be taking a look at the work that Hans Tutschku did for the project. His piece Sparks for piano and live electronics was performed by pianist Mark Knoop at the second FluCoMa concert, at Dialogues Festival 2021. Tutschku notably made use of the fluid.bufnmf~ and fluid.nmfmatch~ objects to build a piano-tracking patch. He then used this tracker to drive audio effect modules using symbolic notation. As with all the ”Explore” articles, there is a series of demonstration patches that can be downloaded and interacted with if you wish to explore the inner workings of the software.

Tutschku describes the piece as the “next step in [his] 30-year investigation of the relationship between piano and live electronics”. He explains that in “an elastic relationship, the pianist is invited to make decisions based on what the electronics are producing at that moment [and that he is] hoping for a two-way interaction between both”. Indeed, from the very beginning of the piece, Tutschku’s experience and mastery of this format is very clear: the balance between the acoustic instrument and the electronics seems perfect. The whole piece has a very smooth flow – we navigate through different moments of suspension, dense percussive explosions and rich harmonic fabrics in a way that seems wholly natural.

Neither the acoustic piano nor the electronics dominate over the other. They truly appear to merge, and the sonic range and possibilities of the acoustic instrument are widely expanded. The electronics allow it to do impossible things: we hear timbres that, while obviously closely derived from the piano sound, are just beyond what we are used to hearing. The electronics seem to delve into the sound, decomposing it, and allowing partials to glide into each other through glissandi, and fragments of the sound are distributed around the space.

In this article we shall examine how some of this was achieved using the FluCoMa tools. We shall begin by briefly explaining what Tutschku wished to achieve with the piece and how it works mechanically, then take a close look at Tutschku’s NMF piano tracker, and finally look at how he uses this data to drive audio effect modules which make use of symbolic notation.

Interactive/Reactive

The piece is called Sparks, and Tutschku explained that this was to reflect the image of two bodies of energy colliding together. The two bodies in this case are two entities that have always been very important in his work: the piano and the electronics. Indeed, this is a format that Tutschku has written for a lot over the years, and it is something that he has developed many ideas about.

When discussing the particular dynamic that emerges in the context of piano and live electronics, Tutschku explained that he puts himself in the place of the listener. For them, the piano is a known entity, and most of the time, the electronics are an unknown entity. He explained that the “duality of something known and something unknown creates something which suggests a direction. It suggests that the known entity is the source, and the unknown entity is the aftermath”. He explained that an important aspect of his work was to move away from that dynamic, not only from the listener’s perspective, but also from that of composition and performance. He wished to move away from a piano and live electronics that would see the electronics as reacting to the piano – he seeks a truly interactive relationship between the two.

The way that Tutschku approaches this goal is to find ways of allowing the electronics to propose new materials. He explained that his “electronic pieces are always a mix of something that happens in real time depending on the signal of the instrument, and pre-recorded phrases and materials. Those pre-recorded materials allow [him] to introduce musical structure and themes in the electronics before they happen in the instruments”. We shall see that, beyond the use of pre-recorded materials, Tutschku also configures the various parts of his electronic setup in a way that will give it space to propose broader musical structure, notably through the use of what we may call symbolic audio effects. Before taking a closer look, let us begin by examining how the piece works.

How the Piece Works

As we see in the video recording, all we see on stage during Sparks is the pianist at the piano. There are two microphones within the piano body which are feeding audio into a Max patch, and this is distributing sound across 8 channels around the audience. As Tutschku indicates in the score notes, it is also possible to perform the piece with only 6 output channels. Due to health restrictions, Tutschku was unable to get to Edinburgh for the gig, so it was Pierre Alexandre Tremblay who was running the patch.

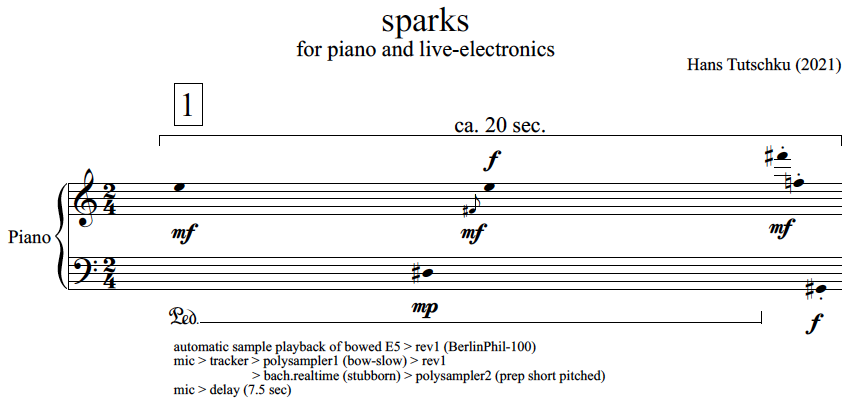

The beginning of the score for Sparks.

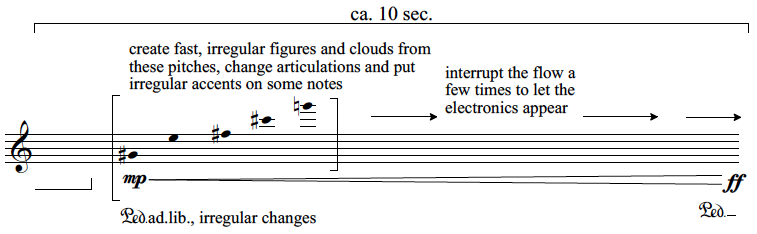

Knoop is reading from a score which, as you can see in the example image, is written in proportional notation. Tutschku uses proportional notation to give the player “pockets of freedom where they can actively create”. There are other moments in the score that contribute to this: for example, in the extract below we see that the pianist is asked to “create fast, irregular figures and clouds” from a set of given pitches.

A moment of freedom for the performer in Sparks.

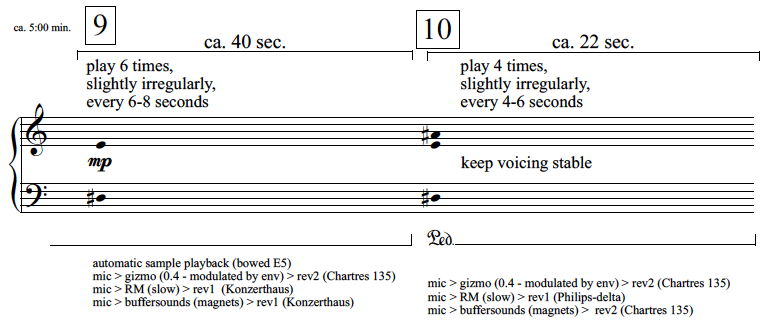

Another example can be seen in the extract below: here, in two sections, the pianist is asked to play a chord a certain number of times with slight irregularities. This reflects certain musical tastes that Tutschku has: he explained that he’s “not a huge fan of real, regular repetition”. He described two opposite extremes of perception: constant repetition of a same element, and constant generation of new material. He finds that neither of these are very musically interesting – he tries to navigate the space between the two.

Repetition in the score for Sparks.

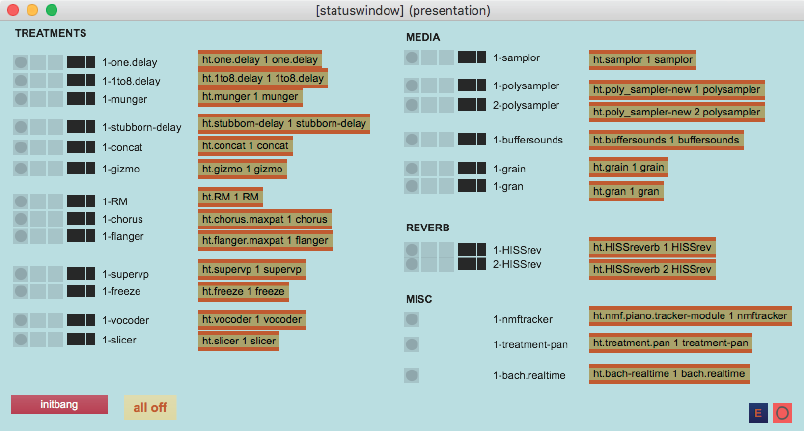

As you will have seen in these extracts, the score is divided into different events that are indicated with the Arabic numerals in squares above the stave. You will also notice that below the stave, for each event there are a number of indications given which correspond to the combination of different audio processing modules that are configured. In the image below we see a patch in Tutschku’s software which displays all of the various modules that are used – these can be soloed and muted as needed. There are essentially three main types of effect modules:

- Those that deal with time (delays, reverbs, samplers etc.).

- Those that deal with the audio spectrum (spectral freeze, vocoder, chorus etc.).

- Those that deal with symbolic structure (see below).

The module status patch in Tutschku's software.

This type of system is something that Tutschku has been developing for many years. He has built an environment that allows him to fluidly experiment with different modules, adding, muting, soloing things as needed. This allows him to improvise with different sonic fabrics, and fine tune the configuration of processing modules so that they sound exactly how he wants them. These configurations can then be saved and reproduced during performance. The pianist triggers event changes with a foot pedal. The modules have been configured in a way that allows Tutschku to avoid sharp, drastic changes between different events.

During an event, the broad configuration won’t change, but the local parameters of the active modules may. Tutschku has developed the idea of “guided random spaces” for controlling these local parameters; the notion that he “knows where [he is] more or less, but there is space for choice for the machine”. He adopts two strategies for this:

- The first is simply by defining a certain range for a parameter.

- The second is by making choices for parameters dependent on what comes into the microphone.

Indeed, the analysis of the piano signal will have a great effect on what is happening across various modules. There are two types of processes involved here:

- Attack detection: triggering things on the detection of a played note.

- Pitch tracking: following the pitch of the incoming signal and using this data to control effect modules.

Let us look at the way Tutschku approached the question of polyphonic piano pitch tracking using the FluCoMa tools.

NMF Piano Tracker

Tutschku explained that this was something that he had tried approaching in a number of ways across his career. It is a tricky subject. Of course, one can circumnavigate the issue completely by using a MIDI keyboard or outfitting a grand piano with a bar and a mechanism that would mechanically track MIDI data of the notes being played. There are, however, few instruments which are outfitted with such devices, and “it becomes more of a hinderance for performing the piece rather than a compositional tool”. He also experimented with the IRCAM’s transcribe~ object in Max (part of the Antescofo score-following package) but found the time lag to be too great.

In his “Traces of Fluid Manipulations” presentation video (that can be viewed above), Tutschku goes through the development of his NMF Piano Tracker. We shall go over the various steps here which are also illustrated in the example patches. We have presented a simpler version to demonstrate the primary steps of the workflow that may be used as a basis for more complicated projects. It will be useful for the reader to discover both a simple and generic overview of the patch that they may explore themselves, and to hear it be explained in Tutschku’s own words and see it working with a real piano in this video.

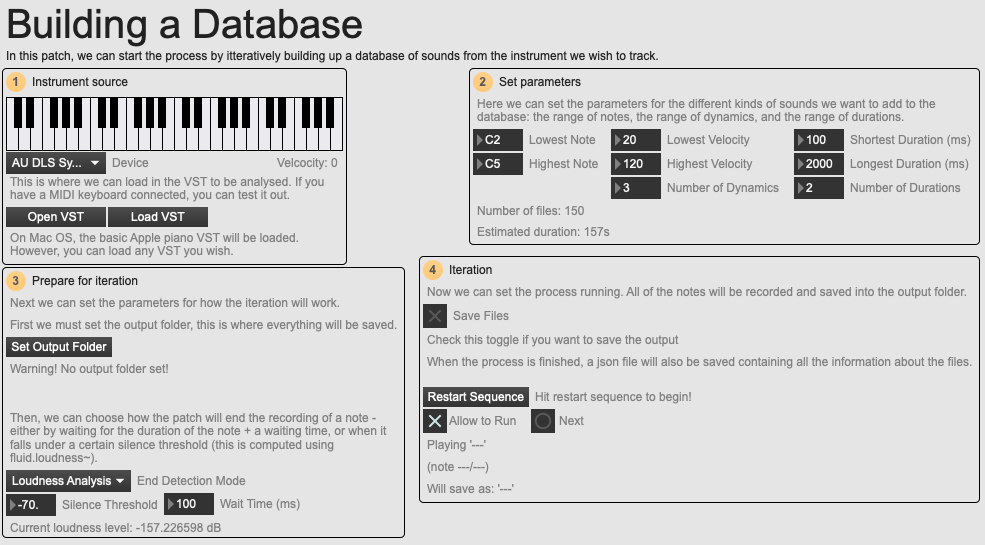

An overview of the 'Building a Database' example patch.

As can be seen in the example patch Building a Database, Tutschku starts by building up a database of different piano sounds. The idea is to build a large database of sounds which represent a wide range of types of pianos. One approach would of course be to record real pianos – however this is somewhat impractical, especially in the context of a global pandemic. Instead, Tutschku used the plugin Pianoteq to iteratively create a database. He could define a range of notes, different piano tunings, dynamics and pedals, and his patch would go through each of these settings, recording the audio as it went. He ended up with a database of over 6000 different sounds.

This process can be recreated in the example patch. Not everyone will have Pianoteq, so it has been designed in a way that allows you to load any VST (on Mac it defaults to the basic Apple piano VST). Like in Tutschku’s patch, you can set a number of parameters and the database will iteratively create itself.

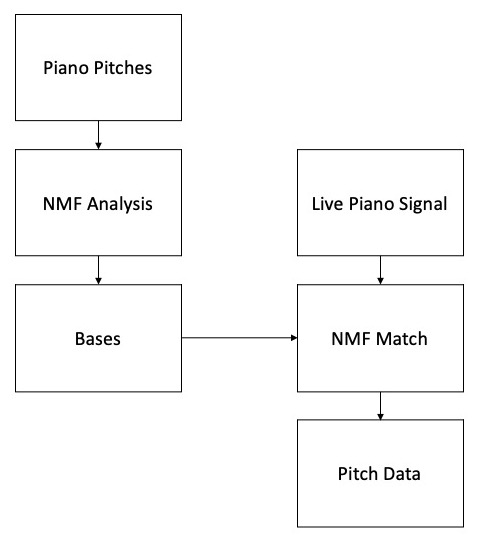

An overview of how the process will work.

Tutschku now has a large database of piano sounds that is divided into pitches. As can be seen visualized in the diagram, the idea will be to match a live piano signal against this database to determine which pitches are currently being played. To achieve this, he uses the fluid.nmfmatch~ object – an object that allows a real-time NMF analysis that matches the incoming signal to a set of fixed bases. Let’s look at this process in more detail.

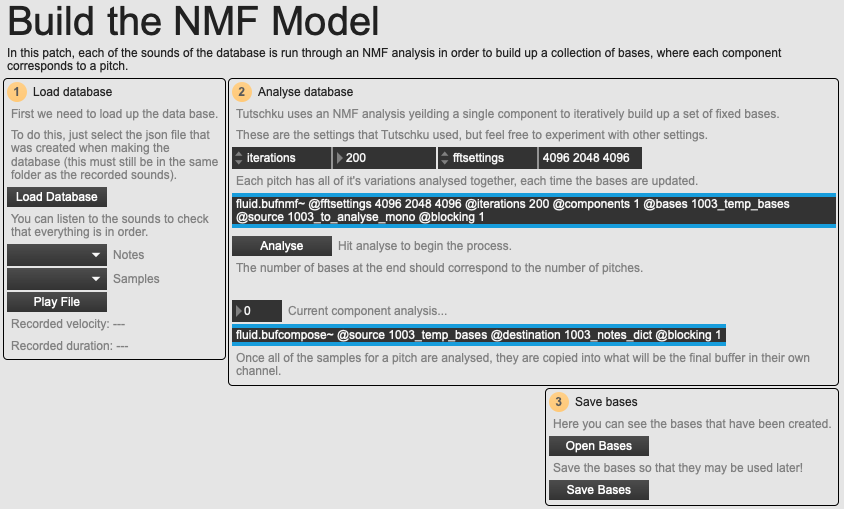

An overview of the 'Build the NMF Model' example patch.

As can be seen in the Build the NMF Model example patch, Tutschku begins with an NMF analysis of each group of pitches. You will remark that for each analysis, he is only looking for one component. Indeed, this is because he already knows what he is looking for – he is not using NMF in this instance to search for objects within the sound, he is using it to build a set of bases that he will be able to use later to find this component in another signal. As we see in the example patch, each group of pitches will correspond to a channel in the bases buffer that will be exported – essentially, each base represents a pitch. These bases can be saved, and used in the next step for tracking.

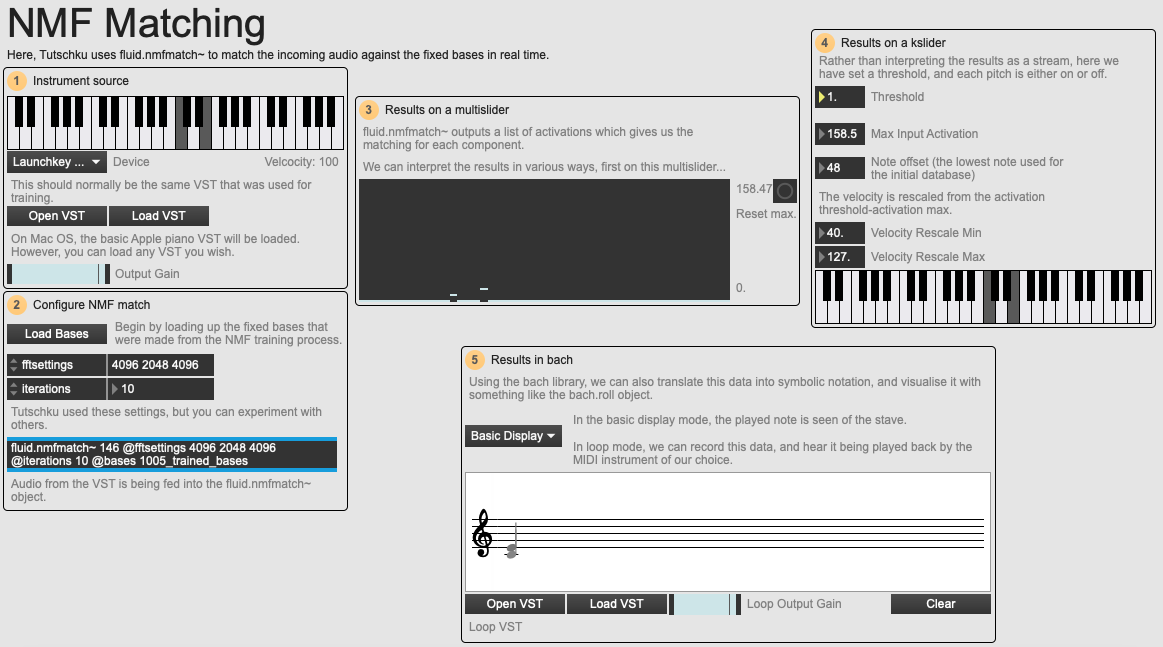

An overview of the 'NMF Matching' example patch.

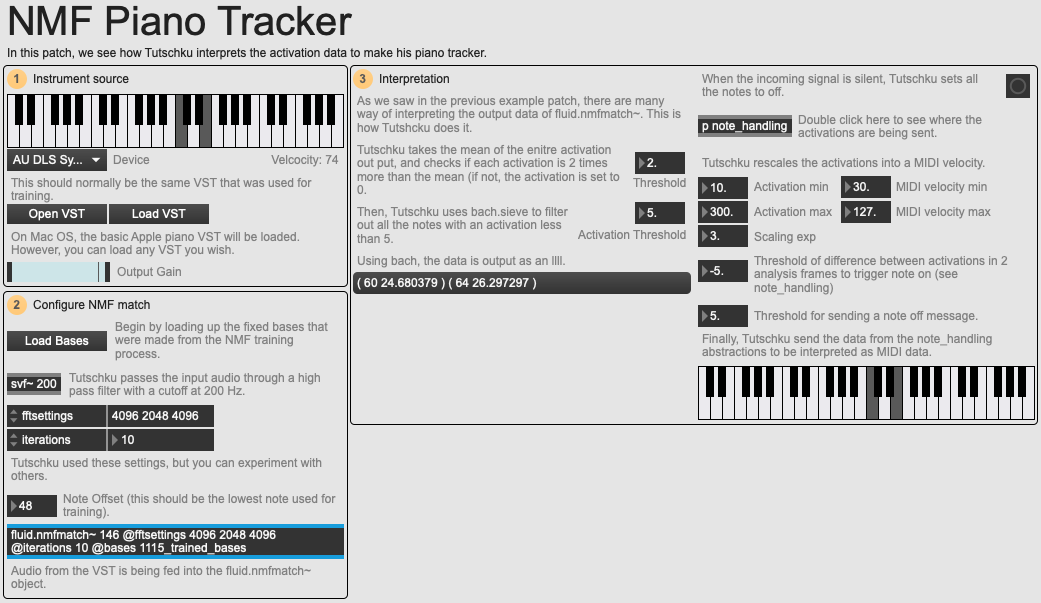

As can be seen in the NMF Matching example patch, these bases are loaded up to be used by the fluid.nmfmatch~ object. Now, when a piano signal is put through this object, the resulting activations will correspond to each note. This data can be interpreted in a number of ways, for example, above we see the results directly displayed on a multislider, on a kslider object, and also in symbolic notation using the bach.roll object. Below we see a screenshot of the NMF Piano Tracker patch which implements some of the particularities that Tutschku deployed for interpreting the data:

- Taking the mean value of the entire activation list and checking if each activation is 5 times greater than that mean.

- Using bach.sieve to filter out activations below a certain threshold.

- Rescaling the activation data into a MIDI velocity.

- Triggering a note on when a certain difference threshold is detected for an activation between 2 analysis frames.

- Passing the incoming audio signal through a high-pass filter to remove redundant information.

An overview of the 'NMF Piano Tracker' example patch.

Tutschku judged the tracker to be about 80% correct when playing up to 4 notes – this also depends on the register (the lower the register, the less reliable it becomes). This margin of error is not something that Tutschku shies away from, he accepts it. He explained that “it’s not a tool to transcribe someone playing Goldberg variations, it’s a tool for me to pretty accurately detect the pitch and do something around it”. Indeed, there are moments in the piece where he takes this known 20% rate of error and uses it as another means for generating the guided random spaces mentioned above. Furthermore, Tutschku explained that the nature of this randomness is useful: for example, if one is playing a low G, the error will not be to detect an F# or a G#, but to also detect the G’s overtones. This will still be related in some way to the G, and therefore becomes musically useable.

Tutschku also explained that he doesn’t make himself a “slave to technology”. He will use this idea as he feels it is needed for his composition, but if, for example, there is a moment in the piece where a reliable detection is needed, he will simply force the machine into doing this. Indeed, Tutschku stated that “we don’t need to fulfil a statement saying ‘I’ve found something technologically and now I’m composing with it otherwise I’m not faithful to my initial project’” – an insightful perspective that again demonstrates his experience with this format.

Symbolic Audio Effects

As we’ve seen in these examples, the pitch data can be transcribed into a bach.roll object, opening up a whole world of possibilities for manipulations in the symbolic realm. Tutschku explained that he can now “do all kinds of compositional transformations that we have been doing for the past 60 years in written music”, transformations such as inversions, mirrorings, stretching etc.

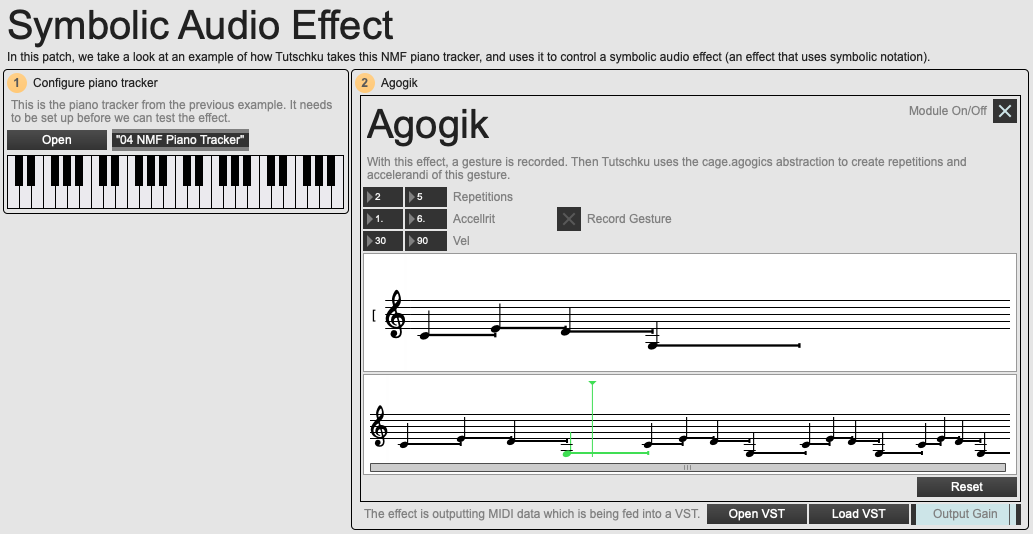

An overview of the 'Symbolic Audio Effect' example patch.

In the Symbolic Audio Effect example patch, we see an example of one of these processes. Using the cage.agogics object, Tutschku has created a module that allows the user to record a piece of symbolic notation which is then repeated and transformed with accelerandi. It is interesting to note that this process is encapsulated within a self-contained module which can be activated, soloed and muted like any other audio effect.

In the video below, Tutschku gives some more examples of these kinds of effect modules: the agogik module, a timewarp, chord and cloud generators, and a stubborn delay. The stubborn delay is something that brings us back to Tutschku’s approach to the question of repetition in music. Here the delay will not be in a steady rhythm and it won’t be a perfect repetition of a particular duration. He is able to create delay lines for each note, “creating these polyphonic textures where every new note coming in creates its own stream of delayed notes, each of them having their own rhythmic pattern”.

Most of these modules are playing back recorded samples, but there is also an example that Tutschku explains in this video of a slicer object where attacks are detected in the incoming signal, and this audio is played back again according to symbolic transformations: changing the speed of playback, playing back notes in a different order etc.

As explained above, Tutschku can fluidly experiment with different configurations of these effects modules, improvise with them, and build up different sonic fabrics for the piece. Coming back to the question of a truly interactive system (and not reactive), he describes the elements that these symbolic audio effects give back as being extremely interesting: “when I improvise with this patch and I play a phrase and then the computer does something with it, it’s super interesting to me, because I hear the transformation in what the computer did – and I can react to it. This is really where I feel as an improvising performer that there’s real interaction, it’s not a reaction anymore, because now I’m reacting to what the transformation of the computer was”.

Conclusion

We’ve seen how the FluCoMa tools helped Tutschku develop a system that is not merely reactive, but interactive in nature for the performer. Indeed, this is achieved for the performer, but an important question for Tutschku is how the audience experiences this phenomenon. Judging himself to be too close to the piece and its development, he is unable to really know if this idea translates into the listening experience. There will probably be as many ways of experiencing the piece as there are audience members; however, it is interesting to learn how Tutschku envisions their relationship with his piece.

He places the idea of plausibility at the core of this relationship. To illustrate this, he offers the example of a clarinet and the audience member’s relationship with it: even if they do not know how to play the clarinet, it comes with a certain cultural baggage. We know what ought to come across, we have a kind of global image of what it ought to do. For electronics, this plausible image doesn’t necessarily exist, and therefore it first needs to be established. He “needs to give the audience anchor points, building a dictionary of known islands, then swim between them. [He] needs these moments of recognizable relationships”. He explained that “a lot happens in establishing local, plausible entities, rules, ways of behavior; when we get used to them, then you can diverge from them”. The kinds of modules that Tutschku can develop in the symbolic, structural realm, thanks to technologies like his NMF piano tracker, seem particularly potent for creating these kinds of meaningful relationships between piano and electronics; in turn bridging a gap and building a meaningful relationship between audience and electronics.