FluCoMa in the DAW and Modular Synthesizer

In the article we’ll be taking a look at the work Richard Devine did for the project, and how the FluCoMa tools can be incorporated into a workflow across the DAW and modular synthesis.

Richard Devine

Introduction

Download the demonstration patches for this article here.

In this article we’ll be taking a look at the work that Richard Devine did for the project around his piece Recursion Constructors. This will be an opportunity to discover how the FluCoMa tools and principles of fluid corpus manipulation can stretch beyond the confines of a creative coding environment, and be utilised in the DAW, and in a modular synthesizer system. We shall be examining how Devine used some of the FluCoMa tools to build up a corpus and how the idea of slices can be approached in a modular context. As with all the ”Explore” articles, there is a series of demonstration patches that can be downloaded and interacted with if you wish to explore the inner workings of the software.

Recursion Constructors was premiered at the second FluCoMa concert at Dialogues Festival 2021. Due to travel restrictions in place at the time, Devine was unable to attend the event in person. He filmed himself performing his piece ahead of time and the video was projected onto a large screen on the night. We are immediately enthralled within the complicated hive that is his modular synthesis patch which is accompanied by a set of intriguing bespoke pieces of percussion. There is a great space within the piece: sounds reverberate around a tastefully constructed chasm. Material staggers from percussive, chaotic, noisy synths and impacts to low, dirty drones and harmonic pads. The whole system oscillates gesturally from complex, buzzing activity to full suspension – all in a manner that is exceptionally controlled and fluid that seems to be unrestricted by the inherent temporal restrictions modular systems can be bound to.

Over the course of his career, Devine has made use of a wide range of different analogue and digital tools for making music. He was notably a user of Max, however when he came to the project he had begun to move away from the computer towards the world of modular synthesis. He explained that he was “tired of using a mouse all day – it lacked the physical interaction that I loved having with an instrument; [with the modular] you get this instant feedback […] you can get to things so much quicker […] to me, being able to fine tweak everything with your hands, just using your ears without looking at a screen – I’ve been able to find much more interesting sweet spots using this interfacing approach”.

There are similarities to be drawn however between his previous Max-led practice and modular synthesis. He compared the two, explaining that “you start out with a blank slate, and you say, ‘what object do I want to use today?’” He said that he still considers the computer to be the most advanced musical instrument that exists today, but that the physical affordances of the modular interface are very inviting to him. In this article, we shall be seeing how principles of corpus manipulation are by no means exclusive to practices in creative coding environments – we shall see how Devine first used the FluCoMa tools in Max but also in the DAW Reaper to build a corpus; then how ideas of corpus, segmentation and slices are approached in his modular setup. Let’s begin by dissecting the physical setup with which Devine performed.

The Patch

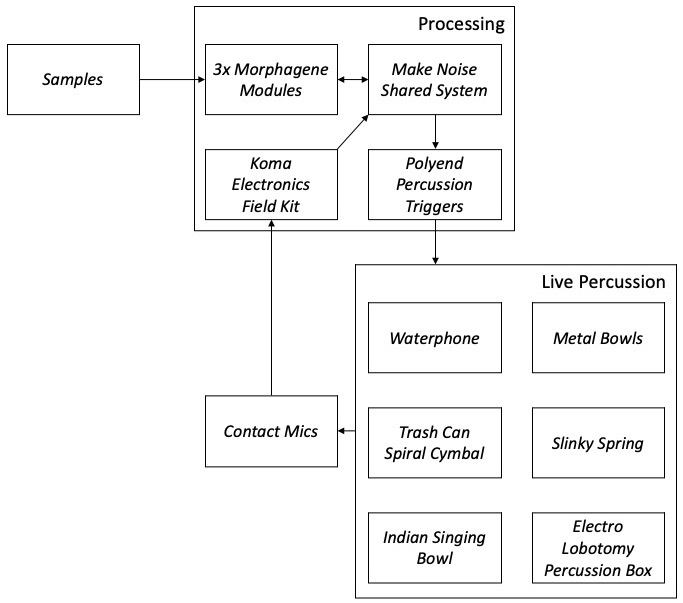

It can be somewhat daunting to observe such a modular system without any knowledge about how it is working, but if we break things down there is a clear structure that can be outlined. First it is useful to conceptualise two primary sound sources:

- Sample playback.

- Live percussion.

An overview of Devine's modular setup.

There is some synthesis happening in the patch, however this is not considered as a primary source of sound material. Devine explained that the synthesis was essentially “there to fill the space”. We shall see also that the idea of sample playback and the navigation of slices is something that articulated that way the system was inherently build up, and drives the way in which it is performed.

Sample playback is handled by three Make Noise Morphagene modules. The Morphagene is an interesting module that Devine described as being the heart of his patch. The module allows the user to load a reel of sound up to a maximum of 3 minutes in length. The user can then set up to 99 splice points. These slices are then played-back in a number of ways, the parameters of which can naturally be controlled by control voltage. We shall return to this module below.

The second main sound source is the live percussion. There were six pieces in total: a waterphone, metal bowl, trash can spiral cymbal, slinky spring, Indian singing bowl, and an Electro Lobotomy percussion box. These are being triggered with control voltage via Polyend Percussion Triggers and picked-up and fed back into the modular system through contact mics and the Koma Electronics Field Kit.

Events within the system are triggered by a René 3D Cartesian-based sequencer which is paired with a linear clock and 2 Wogglebug random voltage generator modules. Devine explained that it was through interaction with the 2 Wogglebug’s that most of the gestural content of the piece was achieved – the rate knob allowing him for example to vary the speed of the system, going from a completely frozen clock all the way up to audio rate. He explained that it was very important for him to “break out of the steady pulse” that is so common in modular synthesis systems. For a more detailed look at how the clock works and general overview of the patch, have a look at Devine’s “Traces of Fluid Manipulations” video above.

Building a Corpus

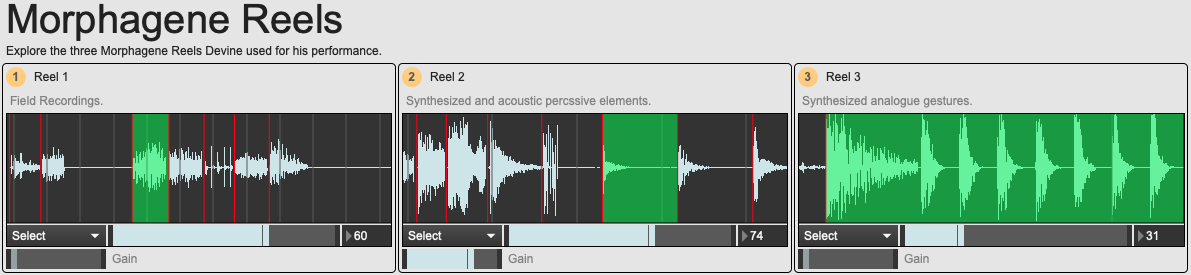

The three Morphagene modules are each loaded with a different reel of sounds that Devine carefully created and curated. They emerge from three different categories of sounds:

- Field recordings (breaking glass, springs, metal, organic materials).

- Synthesized analogue gestures.

- Synthesized and acoustic percussive elements (including recordings of some of the percussive instruments used for the live percussion).

An overview of the 01 Morphagene Reels example patch.

In the example patch 01 Morphagene Reels you can listen to these reels and observe what we imagine to be the splice points that will have been given to the modules. Each of the reels has a distinct identity stemming not only from the nature of the source material, but also the morphological profile of the slices: for example reel 2 tends more towards sharp attacks with long resonances; whereas reel 3 tends towards longer splices, some that can be taken as full loops.

Before looking at the ideas behind the organisation of these reels, we can examine the way in which Devine approached making the sounds. Sound design is a large and important part of his practice: Devine has given masterclasses in synthesis and sound design, and he has designed presets for several well-known plugins (an example of which can be viewed with Unfiltered Audio’s SILO plugin in the video above). Devine used the FluCoMa tools for this in two different forms: Max and ReaCoMa.

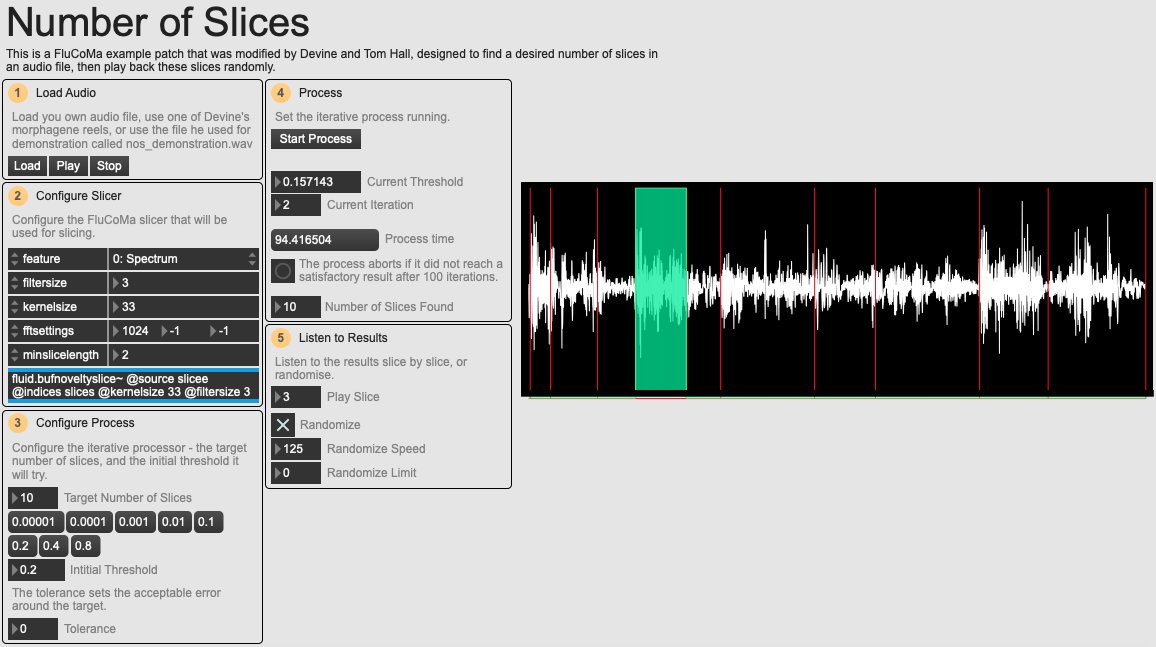

An overview of the 02 Number of Slices example patch.

In his Traces of Fluid Manipulations video above, we see some glimpses of how Devine used the tools in Max for the transformation and construction of new sounds. We see him using some modified versions of the help files for the fluid.hpss~ and fluid.sines~ objects. It is interesting to note that he chooses to opt for the real-time versions of these tools and tends to modify parameters in real time as source material is being treated – an approach that we can see stemming from modular synthesis. Devine also used a modified version of an example patch – developed with help from his friend Cycling 74’s Tom Hall – that allows the user to set a target number of slices to find in an audio file, then randomly play back these slices. This can be explored in the example patch 02 Number of Slices. This process brings the Max environment into a state that is similar to working with the Morphagene. Indeed, we can imagine an important part of Devine’s development process as being able to dynamically and quickly yield a sliced structure from an audio file, and experiment with playback of these slices in various ways.

The second form that Devine cited as being extremely important was with James Bradbury’s implementation of some of the tools in the Reaper DAW, ReaCoMa. ReaCoMa allowed him to navigate sliced audio using novelty slice, and also create new audio from pre-existing content with tools such as HPSS. For analysis, Devine provided us with a collection of sounds he used as source material for creating his new sounds: these vary from loops, to drones, to gestures.

Naturally, the process of transformation from these original source samples to the content that is found on the Morphagene reels is difficult to document, however we can begin to understand some of it using the 03 Source Manipulation patch. Some of Devine’s samples are commercially-sourced, so we can’t distribute them, but in the video above you can see and hear some examples of analysis.

First, there is a two-dimensional corpus explorer which allows us to examine the scope of the sample collection and the final Morphagene splices. As explained in the video, this is good for getting to know the general scope of a corpus. Then, there are a series of patches which produce a ranking of nearest neighbour results across these various collections. For example, if you sort the nearest neighbour results by ‘min’ distance, you can observe that many of the splices of reel 3 were exact copies of slices taken from the modular gestures ‘burst’ source samples. When sorting elements by ‘mean’, we access collections of sounds where the final content on the reel seems to be a combination of several elements from the source samples.

Devine used the FluCoMa tools to stimulate his sound design and rapidly build up a collection of sounds, but how does this articulate itself in performance and fit into the overarching modular system?

Slices for Performance

The situation that the Morphagene module puts the user in, similar to what some of the FluCoMa tools can allow, is an interesting one. The user is asked to curate a collection of slices, a corpus. There is an inherent understanding that these slices will have some kind of structure, there will be some logic that brings them together, that gives them a reason for coexisting within a space. Each slice has a beginning and an end, each slice can have its own internal structure which can be explored, but within the macroscopic scale of a piece, of a performance, of a system, this collection of slices also has something to be explored.

Devine talked about ultimately “trying to put people in a space and tell a story. It’s like a sonic language”. He described begin struck by Morton Subotnick’s idea of having “gestures which are almost like characters, you have a vocabulary that you can use”. We begin to understand the way in which Devine conceptualises of a splice, and of a collection of slices which are intended to tell a story. He described the development process of the reels, and the way in which he carefully placed the slices along the reels: “I went through the sounds in a left to right order […] I could create the evolution of how the piece was going to happen, so all the sounds were moving across this timeline, and I could play and manipulate each one and interject and perform each piece as it moved from left to right”.

This allowed for two major aspects: first, a highly curated and planned grouping of sounds. The different slices of vocabulary are not only intended to be understood across a single reel, but also as a moving timeline across the three: “on each reel, there were groups of sounds which were all meant to be played with each other. I had matching sounds that would work at specific parts”. The second aspect is the posture that this offered Devine during performance: “as I knew exactly what sound was going to be coming out next in the reel, it gave me a great way to plan each gesture, each movement, each transition point. […] you don’t have to worry about what’s happening next in the performance, you can concentrate of the performance aspect”.

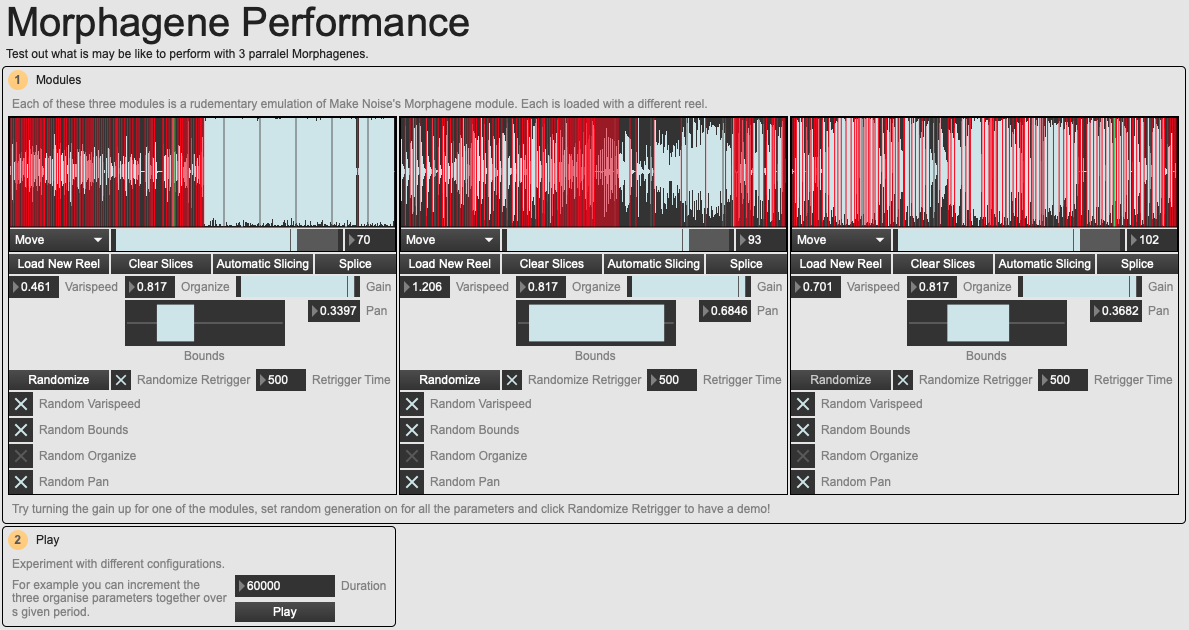

An overview of the 04 Morphagene Performance example patch.

In the example patch 04 Morphagene Performance, we have set up a situation where over a given time duration, the ‘Organise’ function (the control that that tells the module which splice to play) of the three rudimentarily-emulated Morphagene modules will progress in parallel. Feel free to modify this patch, and experiment with performing with these modules in this way to gain an idea of how it may be to perform with such a system. We have also emulated functionality for loading your own collection of sounds to each module and setting slice points yourself or using some of the FluCoMa tools to do this automatically.

Conclusion

Working with slices as a concept in music is a vast and deep field. There are many ways that this idea can be explored, and tools like the Morphagene module, and the FluCoMa toolkit in its varying forms can help you explore these. With Devine’s piece we observe how musical practice can span across a multitude of environments, but can be driven by an overarching approach where the slices, the gestures that combine to put the listener into a space, to tell a story, can be created and manipulated in many ways.