Using FluCoMa to Make a Shared Instrument

In this article we explore the work of Alice Eldridge and Chris Kiefer and how they used the FluCoMa tools to augment their Feedback Cello to create a shared, adaptive instrument.

Introduction

Download the demonstration patches for this article here.

Today we’ll be looking at some of the work that Alice Eldridge and Chris Kiefer did using the FluCoMa tools. These two collaborators came to the project seeking to augment their already well-established feedback instrument, the Feedback Cello. We shall see how they used machine learning and descriptors to create a shared, adaptive instrument which takes improvisation to the next level , and how they approached this system in performance. As with all the ”Explore” articles, there is a series of demonstration patches that can be downloaded and interacted with if you wish to explore the inner workings of the software.

The piece was premiered at the second FluCoMa gig, at Dialogues Festival, 2021. The beginning of the piece serves somewhat as an introduction into the concept of the instrument - (“think of it as a young person’s guide to the feedback cello” quips Eldridge). There are long, sustained, unstable notes which hover between harmonics – we understand that these tones are being fed back into the instrument, and causing the physical body of the cello to resonate. This continues, and as the piece progresses different sonic material emanates as different gestures and approaches to playing are explored: strikes and plucks, different objects are used to strike the cello at various places, and Eldridge explores different styles of playing from traditional melodic gestures to experimental tapping and percussive attacks. True to the concept of a shared instrument, it is difficult (and, as we shall see, somewhat pointless) to try and dissociate what is happening in the electronics and the cello: in an infinite feedback loop it becomes impossible to discern what can be considered source or modulation.

The two performers sit face-to-face. Both are entangled in their own complicated webs of objects: Eldridge the Feedback Cello, foot pedals and a mixer; Kiefer an extensive modular setup and computer running a SuperCollider patch. We glimpse fragments of facial communication between the two musicians, and we understand that they are enthralled in a complex, shared system that they are exploring together. In this article we shall try and gain a better idea about what is happening on stage. We shall start by looking at the Feedback Cello’s development before the project, and then how they approached development for the project and their use of MFCC descriptors and MLP. Then we shall learn how they approach this system in a performance context.

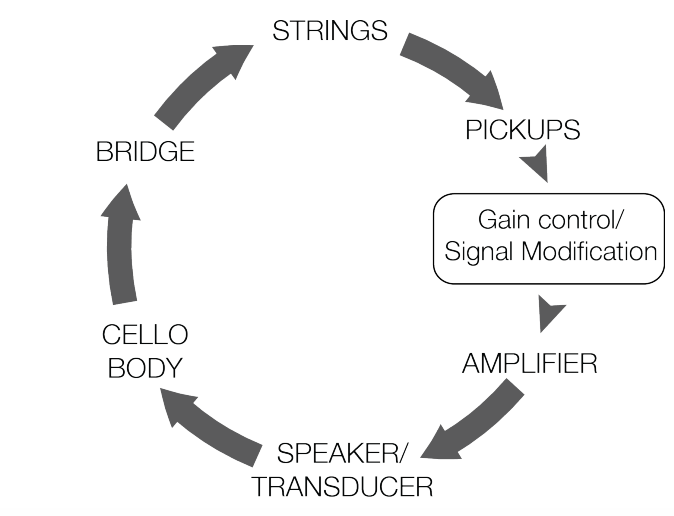

Feedback Cell

Feedback Cell is the name that Eldridge and Kiefer give to their luthiary and performance project which features the feedback cello seen on stage (Kiefer has his own Feedback cello which does not make an appearance here). They describe the cello as a “hacked acoustic cello, custom fitted with built-in speakers and on-body transducers […] the classical cello is transformed into a self-resonating feedback system”. Essentially, as you can see in the diagram below, the idea is that the signal from the strings is captured by pickups and sent for gain control. They are then sent out to an amplifier and speaker on the cello body which in turn causes the strings to vibrate.

An overview of the Feedback Cello, taken from Eldridge and Kiefer's 2017 NIME article.

Eldridge and Kiefer built the first prototypes of the Feedback Cello back in 2016 with Halldór Úlfarsson, who continues to be a close collaborator. Úlfarsson was looking to apply the feedback techniques of his instrument the halldorophone to acoustic cellos. A good resource to learn more about the development and workings of the Feedback Cello is the 2017 NIME paper that Eldridge and Kiefer wrote. In this article they describe in detail the mechanical workings of the instrument, and various approaches to its use in performance (as an adaptive installation, applying extended cello techniques, live coding). With this article, and through hearing the cello in action, we understand that this seemingly simple system “is capable of a wide range of complex self-resonating behaviors”.

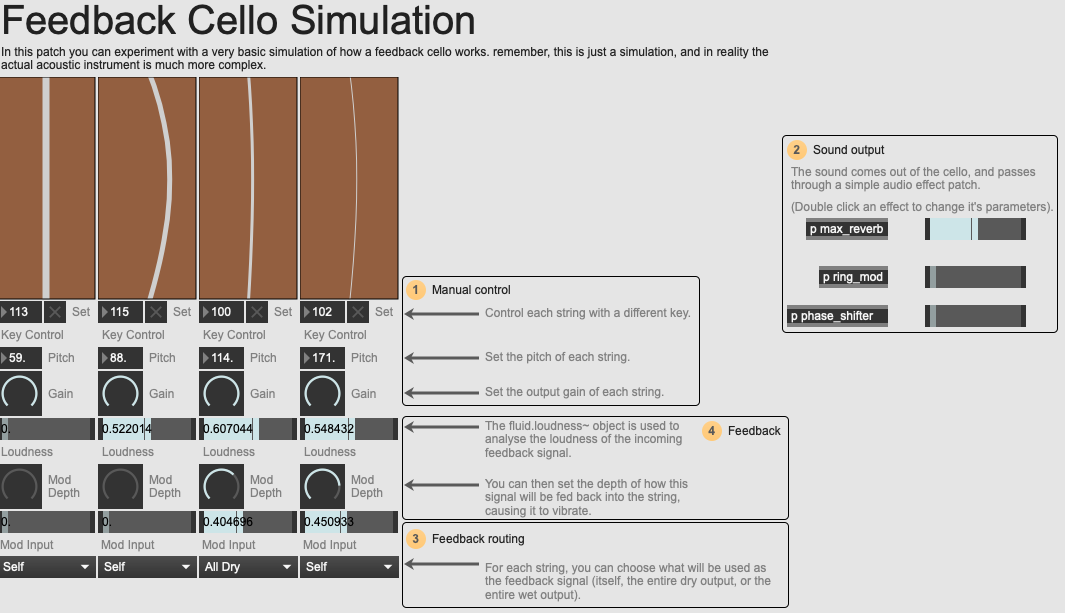

An overview of the 'Feedback Cello Simulation' example patch.

In the example patches that accompany this article, we’ve included a simple simulation of a Feedback Cello. Of course, the actual acoustic, analogue interface that this is emulating is much more complicated. Here, an analysis of the perceptual loudness (using the FluCoMa tools) is being used to drive the ‘vibration’ of strings in the feedback loop. You can experiment with different routings, for example having each string feed back into itself or have the entire output feeding into the string. As simple and as far from the real object this simulation is, it is still a fun patch to experiment with, and begin to get an idea about what it may be like to operate one of these instruments.

Shared Instrument

As you’ll have noticed, the Feedback Cello is not the only part of Eldridge and Kiefer’s setup. We see that in the diagram above, there is a key element called gain control/signal modification which is where a lot of the action is happening. It is this element of the Feedback Cello which has been augmented in FeedbackFeedforward. So whilst there are two people on stage and ostensibly two distinct physical instruments,this is not to be seen as a duo in the classical sense, but as a shared instrument. Kiefer explains that “to think of our performance as a duo, you’d have to think of our instrument as two separate systems – but it’s not!” Eldridge adds that “a better way to think of it is that each physical instrument is an interface into points in the feedback loop of which they are both part”. Indeed, when we see two musicians on stage, each entwined within their own webs of materialities, we can jump to assuming that they are two musicians playing two different instruments. However, as we shall see presently, the setup truly creates a shared, and importantly, adaptive system.

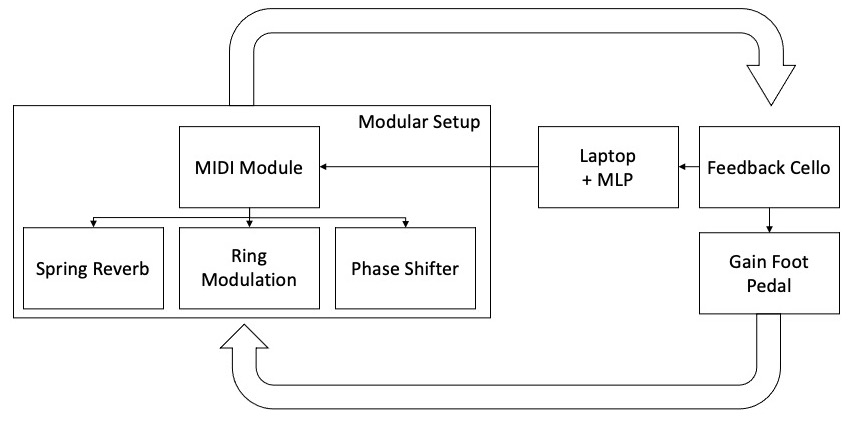

An overview of the what is happening on stage.

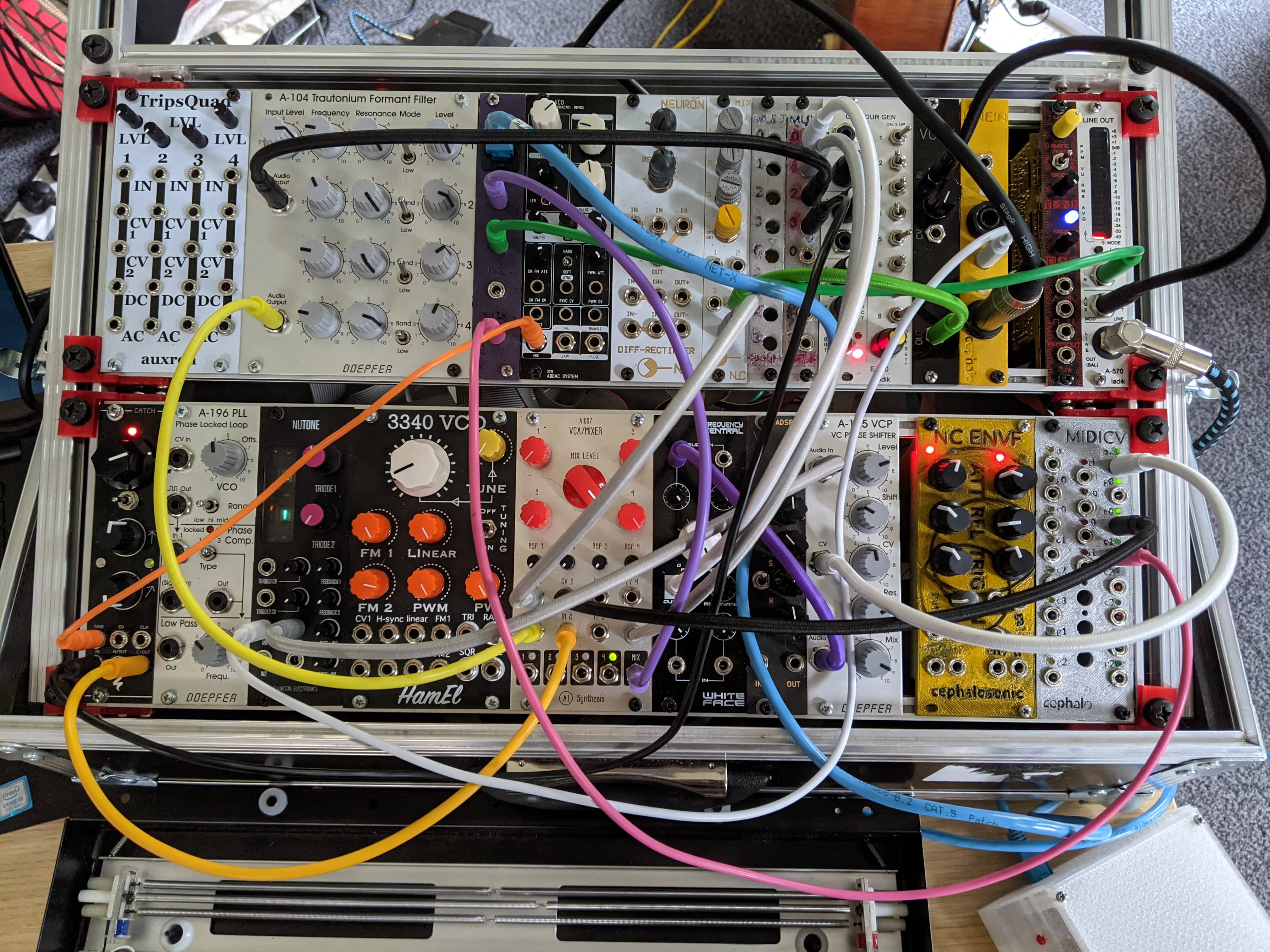

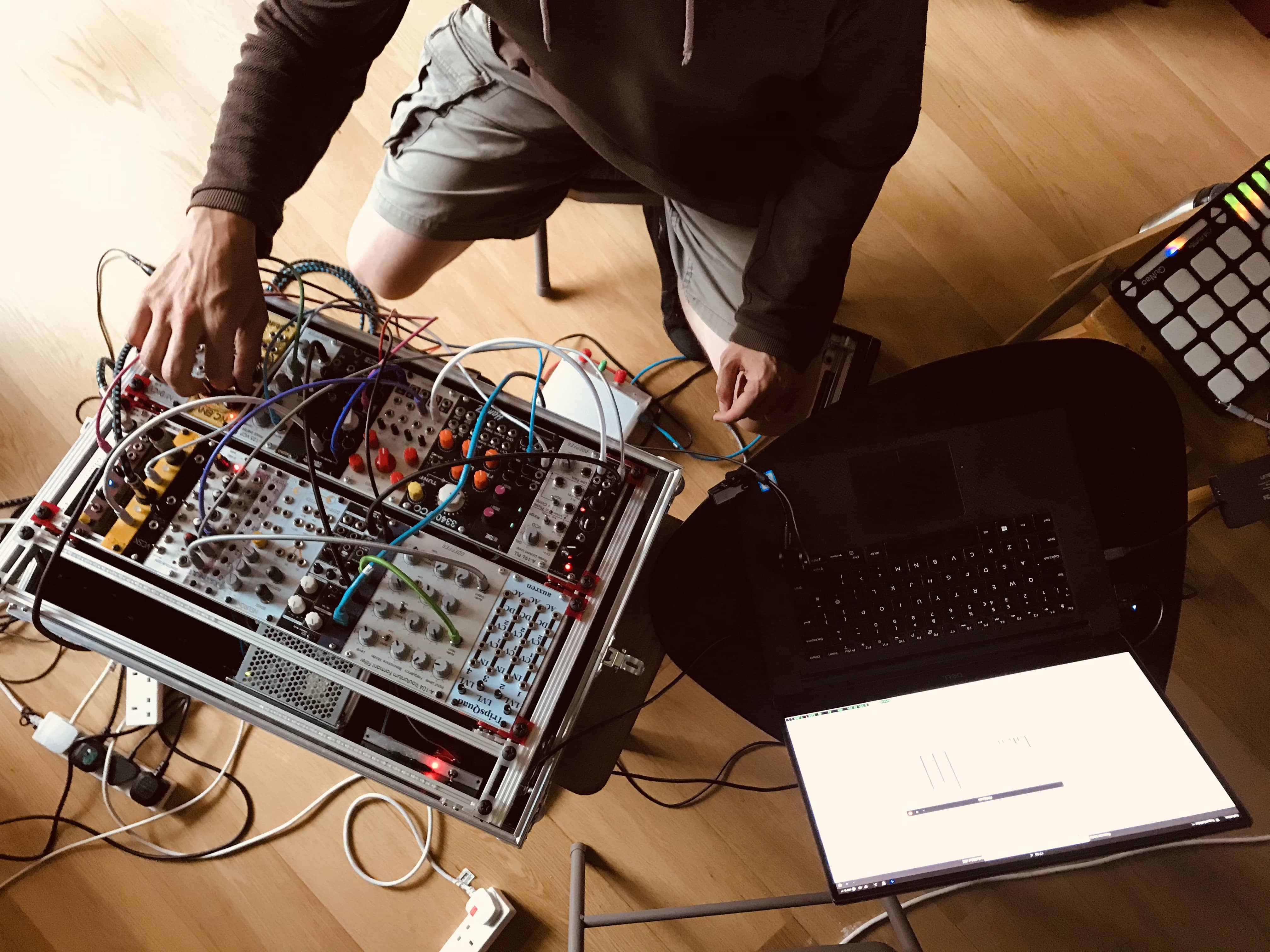

As you can see in this diagram, there are indeed two main sides to this feedback loop associated with each musician. Eldridge is controlling the output of the cello with a gain foot pedal, and the sound is being sent to Kiefer’s modular system. There are more modules in the system which act on the cello’s signal – you can see an image of the patch below. The sound is then sent back towards the Feedback Cello. In this diagram we also see the modifications that were made to this system using the FluCoMa tools. The output of the cello is also sent to a laptop that is running a Supercollider patch. We shall discuss this further below, but essentially, the cello is running through a 20 band MFCC analysis, which is in turn being fed into an MLP regressor, which is outputting three values to a MIDI control module. This is being used principally to control the levels of a spring reverb, ring modulation and phase shifter modules.

A photo of Kiefer's modular setup.

We see then that the feedback cello has two primary functions:

- Providing audio to be fed into the modular system.

- Providing control data for the modular system via a neural network.

Again, due to the shared nature of this feedback setup, it is difficult to disentangle the modular and cello signals: it is the same signal, circulating. The modular is shaping the signals emanating from the cello, and is in turn shaped by those signals as they return from the cello, under control of the MLP. Let’s take a look at the development process and learn why Eldridge and Kiefer looked to FluCoMa’s MLP implementation to augment their system.

Looking to MLP

Using a neural network such as MLP and regression as a means for controlling things like modules, audio effects, synthesizers is a somewhat common use of this technology in a creative setting. There are different ways of approaching this. One very well-known implementation is Rebecca Fiebrink’s Wekinator software. In the context of the project, Sam Pluta, another SuperCollider user, also used a neural network to control effects modules, going from a small amount of input data (2 axes of a joystick) to many control parameters. You can take a look at this FluCoMa tutorial that demonstrates how a neural network can be used to control a synthesizer in order to understand the general workflow.

Here we see the opposite happening: the neural network is taking a large set of input data points (20) and outputting a small number (3). There is also the notable fact that the input data is being derived from the description of an audio signal. The three outputs are controlling 3 MIDI modules which are controlling parameters in the modular synth setup. When explaining why they looked to implement this into their system, Eldridge explained that they saw this project as the “next iteration” of the Feedback Cell project. “When we play two feedback cellos together, we sense a strong acoustic coupling. Any string instruments resonate with each other, but the feedback amplifies this effect. We had been thinking about ways to augment this process, to explore other instrumental couplings using feedback. At the same time I have been interested in keeping my signal pathway analogue, and Chris has just built a modular, so we had been thinking about the modular as a great addition to the feedback cello loop”. This project gave a “chance to explore a new way of doing this”, a way of “coupling the modular synth and the cello in a way that is more adaptive and responsive than just plugging the cello straight into the modular synth”.

Kiefer added that “the role of the MLP was to add interesting complexity and wider, adaptive dynamics into the feedback loop”. The MLP was, with the two musicians, “another agent in the way things work that does interesting and serendipitous things”. There is a balance to be found that also occurs in feedback systems in general – Kiefer explained that “the goals and dreams with these feedback systems is to get something predictable, but also really varied”; Eldridge called it “deterministic but unpredictable”. This interest can be traced back to her PhD work exploring adaptive, dynamical systems in performance and installation: an interest in “harnessing generative creativity of synthetic systems which are responsive to human input, allowing novel forms of hu-machine improvisation and co-creation”. Indeed, many of the artists on the FluCoMa project expressed this goal: this grappling with chaos, wanting to achieve a system that can propose interesting things and surprise you, without being completely out of control. A neural network is a powerful tool for achieving this performance mode, but how does an artist approach incorporating this kind of process into their practice?

Training a Neural Network

Eldridge and Kiefer talked about the development process, and how they approached training a neural network in this context. Indeed, as Kiefer explained, in this artistic context it’s “not like normal AI training where you train it to recognize cats and dogs”; here it was necessary to improvise strategies for training a neural network to give them a system that is not easy to define. Kiefer explained that live coding was an important part of the development process. Indeed, he “doesn’t just see live coding as a performative thing, but as a general approach to making music.”. In each development session, they would try things out, and Kiefer’s ability as a live coder would allow them to do this quickly.

However, before they could even begin to approach training the neural network, it was first necessary to get the analogue part of their system into a stable state. The most important aspect of this is to fine tune the gain structure of the feedback system: they explained that this is “absolutely critical – even a small variance in the gain structure of a feedback system will put it into a completely different state space”. They explained how they would carefully “tune” every component of the system, balancing the gains, making sure that each element was “on the edge of being alive, not being too dominant”. They would even go so far as to completely take apart and recompose the modular setup to ensure that each component was tuned perfectly.

Eldridge uses a mixer and pedals to control the gain structure.

Once this analogue setup was stable, they could begin introducing the digital, MLP-driven part of the system to wreak havoc on it! The question of training the neural network was something that Kiefer and Eldridge stated as being a crucial part of the development process, and one that has no easy answer. Kiefer explained that they explored different methods systematically. One important question to answer was size and variation in training data. They experimented with “lots of little ten second bursts of sounds that were averaged out and connected with different spaces, to just two different pools of long sounds from the cello”. At first, they would try to “peg out the space”, for example “quiet bridge sounds coupled with 2 parameters high and one low, then really loud, harmonically rich sounds, then pizz sounds with sharp onsets etc. with one parameter max and the other min, or all at max, all at min.”

// Extracts from Kiefer's SuperCollider patch.

// Setting up the MLP regressor:

(

~net = FluidMLPRegressor(s,[40,20], activation: 1, outputActivation: 1, maxIter: 10, learnRate: 0.1, momentum: 0, batchSize: 1, validation: 0);

~mode = 0;

~entry = 0;

~inputBuffer = Buffer.alloc(s,~nIn);

~outputBuffer = Buffer.alloc(s,~nOut);

~inData = FluidDataSet(s);

~outData = FluidDataSet(s);

)

// Training the neural network:

(

~net.fit(~inData,~outData,{|x| x.postln;});

)This process of experimentation continued for weeks, and through this Kiefer built-up a certain embodied knowledge about how the network worked. He explained that “in the end, I got an intuitive feel for it. I just told Alice to play, and I’ll collect some stuff. I just got a feel for when and where to go and how to pair things up.” The experimentation process contributed to his learning of how to train the network, but he tried not to think about it too much: “it’s such an imprecise science, if you get a human feel for how it works, then it just somehow works”.

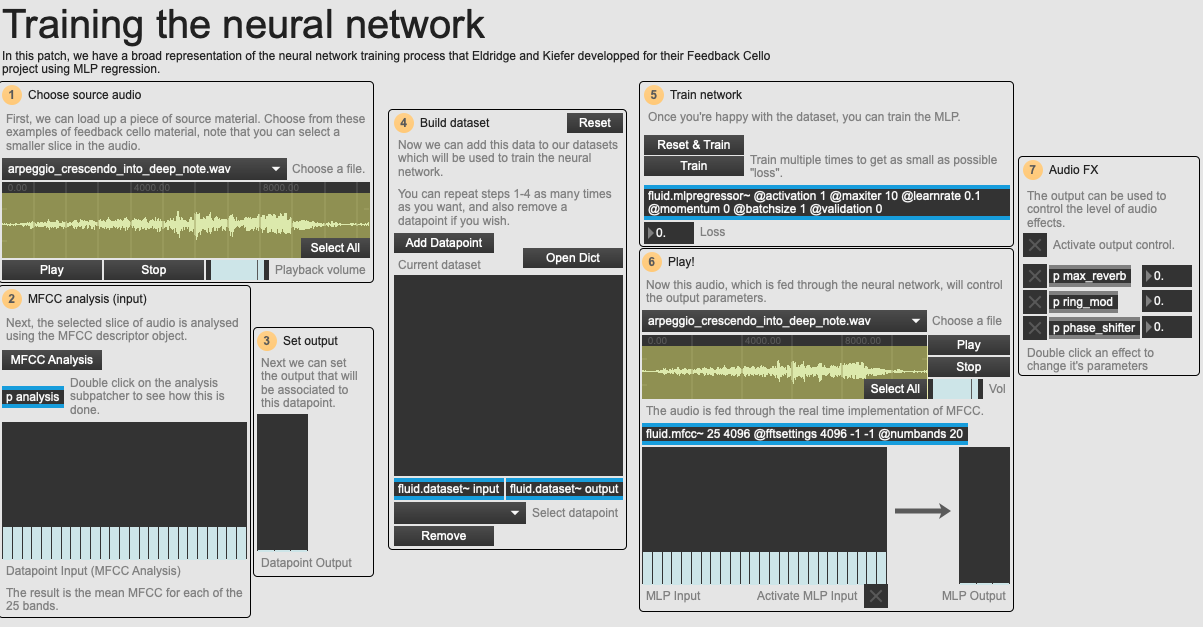

An overview of the 'Training the Neural Network' example patch.

You can test out this kind of process for yourself with the example patch 01 Training the neural network. We have set up a system that is similar to that which Eldridge and Kiefer were working with – an MLP regressor which is being fed an MFCC analysis of the input signal to control three audio effect parameters. We have also provided different examples of Eldridge’s playing on the feedback cello, which can be used to train and run the neural network. Obviously, this patch comes nowhere near to the complexity of the full feedback system. There are lots of other elements that are not emulated, for example the low pass filters that Kiefer introduced to the MLP output to control some of the output jumpiness. However it is a good resource to conduct some experiments and begin to understand the process that Kiefer went through when developing this embodied knowledge around the training of a neural network.

Despite the embodied nature of this knowledge, there is one conclusion that seems to have emerged from Eldridge and Kiefer’s project. Kiefer explained that “if you’ve got a deep network, you need loads and loads of data to get it to do something useful”. They, on the other hand, found that the light-weight approach worked best for them, and provided the most interesting results. Under-training, it seems, can be a good generator of surprise and serendipity.

Shared Instrument in Performance

As you can imagine, this system delivers quite a unique and bespoke interface to perform with. It is a shared instrument; it is also a very delicate instrument: the fine tuning of the gain structure means that it can be difficult to get things to work correctly in a new performance space. It is a challenging instrument for the musicians: indeed, Eldridge is using the cello not only as a means for generating sound, but also as a controller for the modular setup. These two functions are fulfilled simultaneously: she explained that there was “a pretty steep learning curve”. All these elements combine to make performing with this shared instrument a real challenge, and a notion that is still being developed and explored through Eldridge and Kiefer’s ongoing practice.

The system being deployed in a performance setting.

I talked with the duo about how they felt the performance went, and despite being generally positive about it, there was an element of disappointment about the actual gig. This was partly due to the fact that the sound check went exceptionally well. Eldridge explained that they discovered that “the room had the same resonant frequency as the bottom string of the cello. [Pierre Alexandre Tremblay tuned the PA so that they] could get feedback not only in the cello/modular system, but in the whole room”. This was a striking moment which Eldridge decried “made her heart melt” – unfortunately this didn’t occur during the gig (pesky audience!).

Kiefer at work adjusting the system.

I wanted to learn exactly how each of the two musicians approached performing with this system. Kiefer explained that they “have to anticipate each other a bit, because it’s a shared instrument, we have to figure out if what we’re doing is working. If I make a change, I’ll watch Alice to see if the change is useful.” Indeed, during the performance, despite having to each deal with their own complicated webs of materialities, we see a lot of facial communication happening. Kiefer explained that “there are pragmatic things. I could accidentally make the system really dead or make it unplayable for Alice”. Kiefer considered this a systemic problem with the instrument, as it creates an imbalance of agency where “the modular has a bit too much influence over the system”. This is a concept that will undoubtedly be addressed in the future.

Eldridge compared the system with a more typical improvisation of two people on separate instruments. Like in a normal improvisation setting, “when it’s going well, you kind of merge together into one entity. The boundaries between you and your instrument, and you and the other person and their instrument all merge. When it’s not going well, you don’t feel completely integrated. There’s a sense of separation it all becomes a bit deliberate and loses life. When it is going well, playing this shared, adaptive instrument puts you right on that edge where you have to follow the sound and the feel of the instrument moment to moment, and you are doing that together, so planning and deliberate actions are less relevant. It is really quite blissful when it works.” This is interesting to hear, as we feel that the very premise of this system, the shared instrument, is attempting to accommodate this very concept: the merging of player and instrument, of two musicians.

With the MLP integrated into the system, and due to it’s general nature, there is a “narrower tunnel that you need to get to. There’s quite a small area where all the good stuff happens”. With a normal cello, if a string breaks for example, you can deal with it in an improvisation setting. However, if one of the elements fails here, it’s a lot more difficult to overcome – a feedback system by nature is quite fragile. But “when it does happen its quite a profound experience”.

Conclusion

Finally, Eldridge offered her perspective on the essence of this shared, adaptive instrument. It has a lot to do with trust and reliance. She explained:

You can’t care too much about what it sounds like in advance of the moment […]. Chris will have changed something in the instrument, but he doesn’t know the effect of that change until I do something different, and then the MLP might shift things again. So you can’t plan to do something with an anticipation of how it will sound as the soundworld and even mechanical response of the instrument may have changed. You have to switch on to that, up to a different level of improvisation as established sensory-motor contingencies may have shifted. There is something quite blissful in that, it really puts you ‘in the moment’ and makes you drop plans and preconceptions. It demands and rewards pure exploration. This situation of both individual and shared agency is quite unusual, it feels like a fresh way to relate with, to interact with and co-create with another musician.

This is a fascinating situation for two musicians to find themselves in. This feedback system, augmented with the presence of this supplementary agent, the MLP, pushes them into a state where they must always be on their toes, always be taking risks, always keeping things moving. They have created a system which not only invites collaborative exploration, it demands it. All of this comes together to create an intriguing and compelling spectacle not only to observe, but surely also to play.