Ecosystemic Interferences

In this article we look at the improvised performance practice of Raw Green Rust, and how they use the FluCoMa tools to hijack each other’s outputs in Ableton Live and visualise their performance in real time using Unity.

Introduction

Download the demonstration patches for this article here.

Note that some of the example patches use a custom build of the FluCoMa objects. You will need to drop the externals provided into your Max/Packages/FluidCorpusManipulation/externals folder.

In this article, we shall be taking a look at a trio of musicians: Raw Green Rust – comprised of Jules Rawlinson, Owen Green and Dave Murray-Rust. Raw Green Rust gave a performance at Dialogues Festival 2021 using Green’s software Regulatory Capture. As the reader may know, Green was one of the developers on the FluCoMa project, and naturally his Regulatory Capture software makes heavy and interesting use of some of the tools. We shall be taking a look at Raw Green Rust as a trio, and at some of the software they use during performance. As with all the “Explore” articles, there is a series of demonstration patches that can be downloaded and interacted with if you wish to explore the inner workings of the software. As explained above, some of the examples use a custom build of the FluCoMa tool, so it will be necessary to drop the two externals found in Owen Green FluCoMa Build into your Max/Packages/FluidCorpusManipulation/externals folder (replacing the fluid.libmanipulation.mxo external). If this has been done, you should see the following message in your console when you boot up Max.

Checking that the custom build of FluCoMa is installed correctly.

We are faced with a curious setup: three musicians that each seem to be entangled in their own complex webs of physicalities, one is even far off, and being beamed-in via technology. Despite this, as soon as they start playing, we understand that what we’re hearing is deeply interconnected, the three seem to be sticking fingers into the same suspended network of sound that floats between them. They prod and pull at this entity, stretching strands out and sticking them to parts of their setups, only to have these strands snapped or pulled away by another who will wind them around ever-changing spokes or pull them towards themselves.

Many of the sounds we hear are characteristically snappy, almost disparate in parts – yet the never-ending continuum that is being projected behind the musicians creates a sensation of incessant forward movement and drive. We hear dregs of Dub, its form has been wholly deconstructed, its guts strewn across the floor. Fragments of its sound are picked up and delicately splattered. Soft pad-like textures will emerge momentarily before dissipating and being sucked into the passing gale. From time to time, this continually evaporating present is punctuated with striking, complete sounds – yet they stand far enough apart from each other to never let us forget that we are flying through the remains of edifices in a wasteland occupied by dust and sparks.

To explore Raw Green Rust’s practice, we shall start by taking a look at how the trio started and what some of their recurrent goals and objectives have been over the years. Then we shall take a close look at two important pieces of software used at the performance in Edinburgh that bridge between the three musicians: Green’s Regulatory Capture software, which is running in each of the three’s Ableton Live sessions; and Rawlinson’s visualisation software UniSSON which is being projected during the performance from Unity.

A History of Interferences

The trio have been performing together since 2008. Outside of their respective PhD research the project was an opportunity to make music in a more relaxed context (Green: “without having to address issues of Western concert music tradition”) and allow themselves to use samples and reference things like Dub. Green also cited the ability to use off-the-shelf controllers in this context as being quite liberating. Their practice developed progressively, initially each tending towards a certain role, before as Rawlinson explained, “over time there’s been a convergence […] in terms of what each of us contributes and what each of us draws out of the group.”

Indeed, the Raw Green Rust project is one of three-way interference at several time scales. As we shall see, ideas of interference, and the concerns around agency that come with them, are fundamental to the way in which the trio perform. However, their playing together and this tendency of interference has also inflected each of their improvisatory practices over time. Each of them has developed a unique setup that remain characteristically open and able to capture samples on the fly. When developing their setups, the three are all acutely aware that the other two are always changing, be it in the software or hardware, which makes it impossible to expect anything in any certain way (apart from perhaps, the unexpected). This is a situation that the trio has purposely cultivated and one that makes for an intriguing dynamic both for spectator and performer.

Let us examine how these approaches to interference have developed over the years. An initial example of interference arose from the three having a shared clock. This allowed them to, of course, synchronise loops and other types of activities, but it also led to what Rawlinson called “opportunities for mischief”. Indeed, any one of them could change the internal clock on everybody’s Ableton Live session, which meant that you could find yourself suddenly going from a manageable 110 to an insane 800 BPM which could make some clock-based processes completely break down. Rawlinson explained that this quite organically “became a feature of some of the things that we were doing”. It’s remarkable to see how in the field of creative coding, when given a tool to help them do one thing, artists cannot help themselves but to hijack it and make it work for them to do something completely different!

The trio also share audio data as well as control data. One significant example of the use of both of these streams is Green’s Exchange. Value Max for Live tool which Rawlinson described as “quite an important moment in having to respond because the machine listening process was directly interrupting my agency”. Green developed the tool in a response to what he calls “toothpaste form”. The trio had been playing together for 4 or 5 years, and he had noticed the phenomenon which he describes as “this thing in electronic music where density becomes decoupled from effort”. Essentially, you can set processes rolling which can go on for hours, and layer similar things on top. He noticed that their laptop improvisation tended towards this, and that “there wouldn’t be very much modulation of density compared to what could be done”.

The idea behind Exchange. Value was to intervene, and essentially stop each of the member’s playing if the algorithm judged what they were doing to be too boring. It took in your control data and your audio, and made a judgment in the following way:

- If you’re doing lots of physical gestures yet making little sound, then this is deemed interesting.

- If you’re barely moving at all and you’re making loads of sounds, this is also deemed quite interesting.

- Anything in the middle is boring!

The consequences of being boring are to have your played stopped, and not being able to make sound again for an amount of time proportional to how long it took you to get stopped. This is an interesting mechanism, that can take a fair bit of courage to use in performance. Indeed, Rawlinson recounted one instance of a concert where the worst/most amusing thing that could happen occurred: “there was a brilliant moment in one of our performances where as a result of the mechanism, each of us got cut out at exactly the same moment, and we weren’t able to make any sound at all. We’re left just looking at each other. But it allowed time to take stock…”.

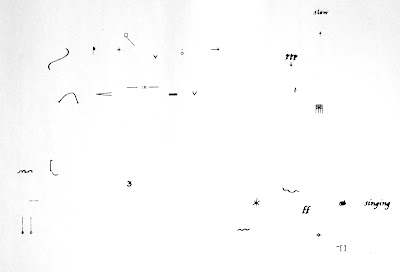

Christian Wolff’s score Edges.

The implications of this kind of tool, however, go far beyond one performance. Green explained his experiences playing things like Stockhausen’s text scores, or Christian Wolff’s experimental notation pieces form the 60s, and how “they really condition the way that you play, even after you’ve finished with the score”. He feels that this was indeed the case, citing an occasion when they were no longer using the tool, and people in the audience who knew about the software assumed that they were. This is a powerful aspect of technology that goes beyond its immediate use, and something that Green wished to capitalise on with his latest software, Regulatory Capture.

Regulatory Capture

As with Exchange. Value, Regulatory Capture started with a remark about the group’s playing. Green explained that “coming off the back of doing a lot of mixing and editing with stuff we’d done, I noticed that our retrospective temporal window for stuff that we were grabbing […] was quite brief.” He wanted to see what could happen if they had a system that could reach back amounts of time like ten minutes and see what consequences that would have on form. This is another venture in the quest to combat toothpaste form, the first was to impose reflexes in the group’s playing, this second to give them a tool for looking back, and indeed, have moments of the past be reimposed upon you.

Green had to make something that would be fairly agnostic about what other people were doing – again, we have this fundamental idea that the parts of this trio are in constant motion, and to try and plan for any specific thing would be fruitless. This counts not only for the types of things that each of them will play, but also very practical things like the ways in which they will do their routing within Live. The only real stream that Green can rely on is audio. The first step is therefore to take their audio and have a way of agnostically finding things in this audio. This departs from usual FluCoMa workflows that we may have looked at across this series of Explore articles in as much as, having no real assumption about what it is we shall be slicing, it is not a simple matter of just choosing transient slice, onset slice or even novelty slice with one of its various features.

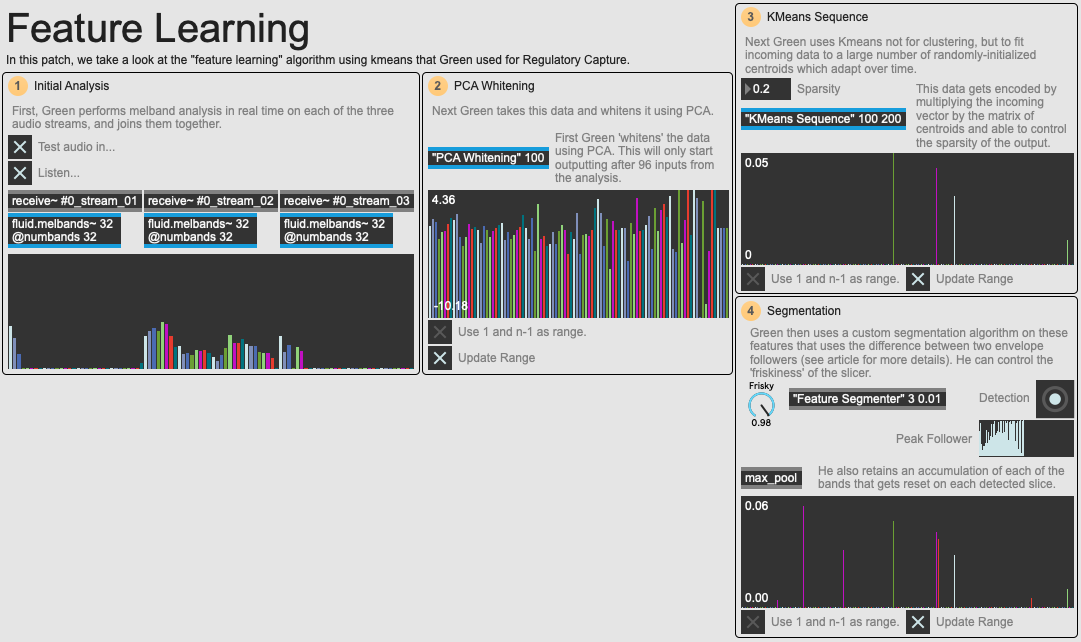

An overview of the 01 Feature Learning example patch.

Green pushed FluCoMa to its limit to try and accommodate this desire and looked to a technique called feature learning that can be read about in this article by Adam Coates and Andrew Y. Ng at Stanford (2012) which describes the underlying process, or this article by Justin Salamon and Juan Pablo Bello at New York University which describes an application of the technique for urban sound classification. The ideas can get quite complex, so things have been demonstrated, we hope quite clearly, in the example patch 01 Feature Learning (see an overview above). In the example, we have set up a situation with 3 incoming audio streams, like the case of Raw Green Rust – these can easily be replaced with your own content if you wish to experiment.

As you can see in the overview image, the process starts with a somewhat typical FluCoMa analysis of the audio that looks to get a general idea of the timbre: a melbands analysis into 32 different bands. These are then grouped together and treated as one object for analysis. This is already somewhat interesting in itself – Green chooses to perform this analysis on all of the audio together, reinforcing this idea of each musician participating in one interconnected, somewhat homogenous (at this conceived point in time) body.

PCA Whitening abstraction.

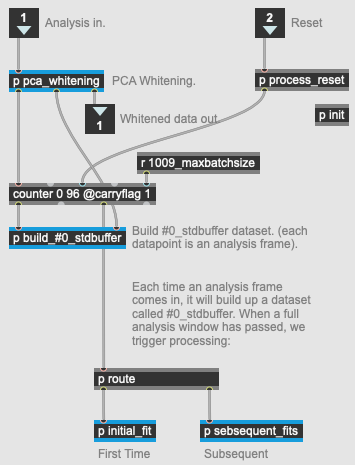

Next, Green whitens the analysis data using PCA. This is something that was not a part of the toolkit at the time, and Green (despite his position as developer in the project) made his own build of the tools to implement this. This feature has since been implemented, but at the time, this was somewhat experimental. Whitening makes the data it is given spherical, which means that each dimension will have roughly the same standard deviation. Indeed, there is no dimensionality reduction happening here as such, this is a process that is coupled with standardization to sanitise the input data and make further analysis more effective.

In the example, we also see that Green uses a custom-build of the tools to implement incremental fitting with his standardization and PCA objects (this is why it is necessary to, as explained above and in the examples, replace the fluid.libmanipulation.mxo file in the Max externals folder with the one given with the examples). He can send the message partialfit to these objects, which will progressively build up and adapt the model with each passing analysis window. This makes for feature learning which will gradually adapt as time moves on.

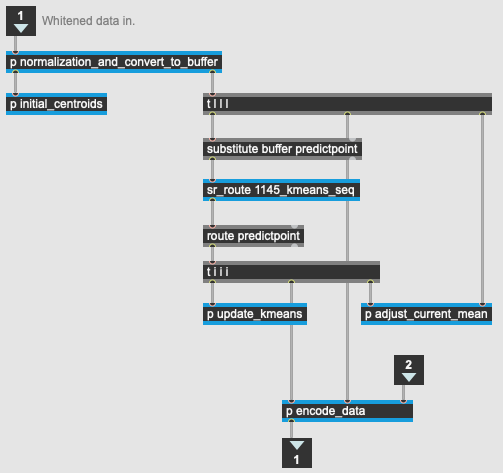

Spherical K-means abstraction.

As explained in the articles that Green referenced, we then use a spherical k-means algorithm, where k will typically be much larger than the dimensionality of the input data (here k is 200, and the input data 96). In this patch, we start by randomly initializing centroids from a gaussian distribution, and L2 normalize them. Then for each analysis window, “we assign samples to centroids, we update the centroids, and finally we normalize the centroids to have unit L2 norm.” (p. 2). Spherical k-means uses cosne distance instead of standard Euclidean difference to measure difference, however this is not implemented in FluCoMa’s k-means object. This is why Green fakes it by ”taking advantage of the fact that the cosine distance happens to be proportional to the Euclidean distance of the L2-normed vectores, which basically snaps each vector onto the unit sphere“.

Finally the resulting data is encoded using one of Green’s custom FluCoMa objects, fluid.bufmatmul~ which will do a matrix multiplication between two buffers: “assigning each sample to its closes centroids […] resulting in a binary feature window whose only non-zero elements are the n selected neighbours” (p. 2). He is also able to control the sparsity of this encoding.

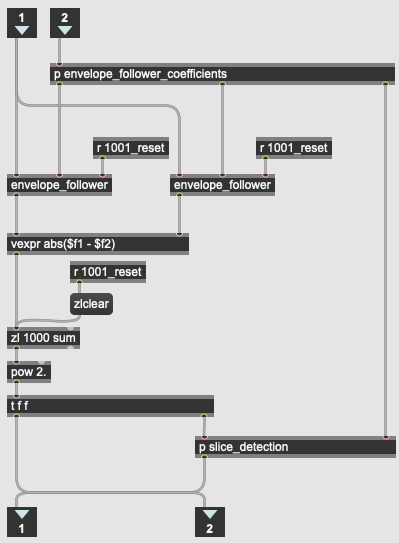

Feature Segmentation abstraction.

This can seem quite complex, and we would be remiss to not admit that this is getting into some fairly high-level machine learning concepts; and as Green stated, “it’s pushing right against the grain of what you can actually do with FluCoMa.” In any case, in the example patch you can visualise the results. We see that we output a vector of 200 values which will have some sparse spikes, and this is data that Green can use to perform segmentation. This is done fairly simply by looking at the differences between two envelope followers on the data and an implementation of the algorithm in this paper by Nicolas Keriven, Damien Garreau, and Iacopo Poli. As suggested in his reference article, he also pools that maximum value of each of these bands between segmentations, gaining a better picture of what happened during this time.

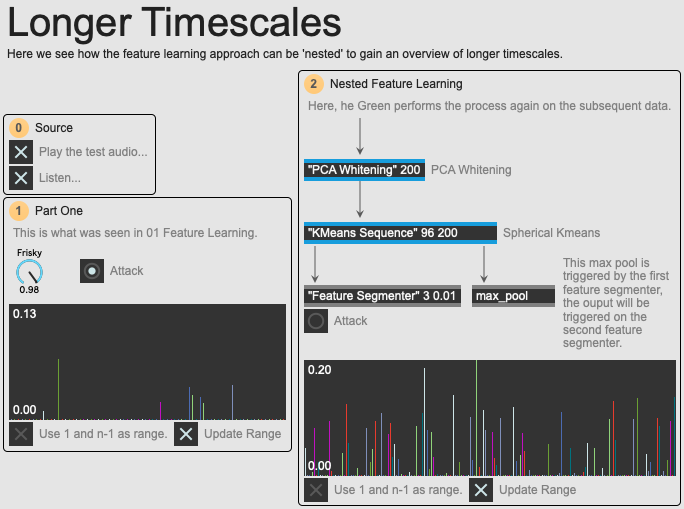

Overview of the 02 Longer Timescales example patch.

One aspect of this technique is that it is nestable. Green performs the same process again on the output data to get longer slices operating on larger timescales. All in all, this is a fairly computationally lightweight technique that allows Green to make agnostic segmentations about the audio that is incoming and keep events in memory to have them intervene later on. As indicated above, at 10 minutes, the memory for the Regulatory Capture patch is quite long, and Green keeps an account of these events and has them come back much further down the line. The algorithm will choose what segments to play back by “looking through a history of all the things its ever heard, and say, ‘what’s similar to this?’” However, as we have seen, the feature learning that Green has implemented is adaptive, and what may have been similar to one analysis at one point, may be completely different at another. Green explains that that’s all “part of the fun”.

Spectacle

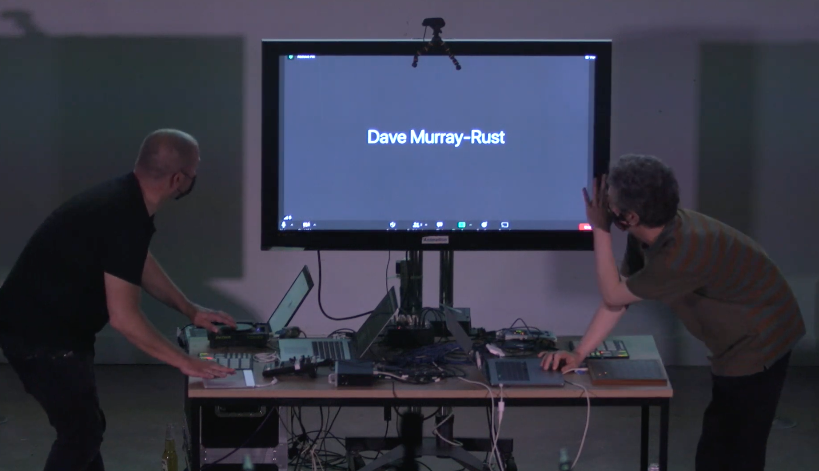

Another import aspect of the trio’s playing is spectacle. This is inflected in several ways: one obvious way for the audience is that of the audio visualisation that was projected onto the huge screen above the trio during the performance; however, another is the need for us and them to see each other. Rawlinson explained that “while we’re a laptop trio, the laptops are the least important thing of what we’re doing. […] seeing each other play, the visual cues we get from each other, and the gestural aspect of performing, from an audience perspective, is one of the most exciting things that people can get out of a Raw Green Rust performance”. He went on to explain that it’s important for them to be able to unpick what other people are doing, and that it was a very instrumental performance practice.

Saying farewell to Murray-Rust during the performance.

During the concert, there was a dramatic moment where Murray-Rust, who was performing with the others via Zoom, was disconnected from the performance. His camera cut off, and we watch as his bandmates notice after a few moments. After a quick wave from Green, the performance goes on. In reality, it was just the camera that had been lost, and Murray-Rust was still able to continue playing. However, considering what Rawlinson has said to me about how important it was for the three to be able to see each other, I asked how this may have affected the performance.

Both Green and Rawlinson said that, in hindsight, “it would have been so easy for us to send a message to Dave, saying, ‘your camera has packed up, please come back’”. However, through what Green calls “on-stage stupidity” and what others may call being preoccupied with other things, this didn’t really occur to them. One thing that did help them a lot was the visual representation on the big screen. Indeed, it turns out that what is being projected goes far beyond just being for the audience’s benefit – it is something that the trio use themselves as a form of immediate, experimental notation.

The software is called UniSSON (Unity, SuperCollider Sound Object Notation) and was developed in Unity and SuperCollider by Rawlinson and Marcin Pietruszewski (for Regulatory Performance, the SuperCollider part of the software was replaced with a Max-based FluCoMa implementation). Rawlinson was already interested in visualisation and experimental notation as part of his PhD, and it has been something that he has closely developed over his career. Let’s take a look at how things work in the software used for the performance.

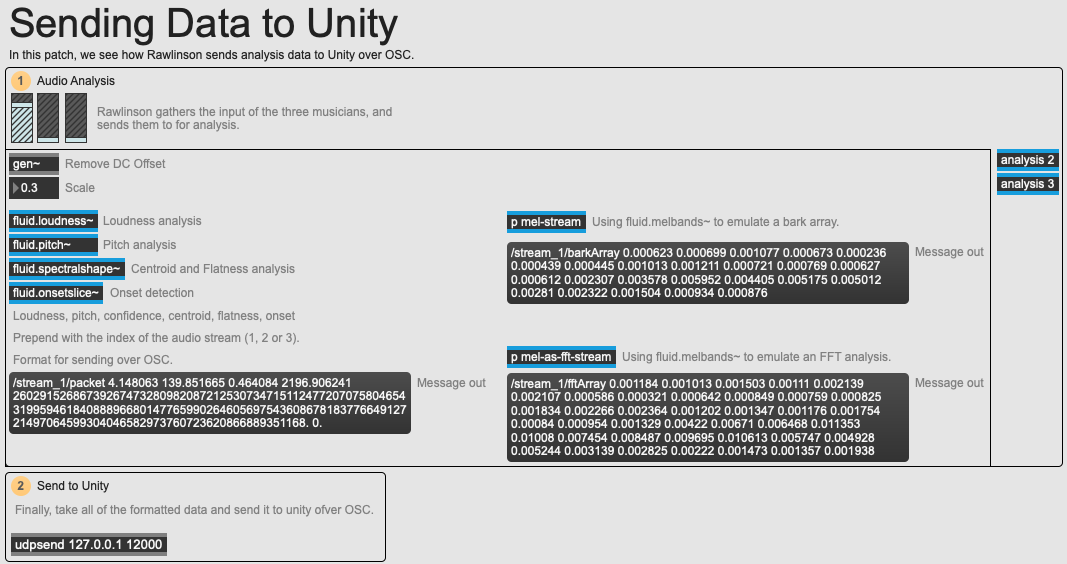

Overview of the 03 Sending Data to Unity example patch.

In the example patch 03 Sending Data to Unity we see how Rawlinson uses an array of FluCoMa real-time analysis objects: loudness, pitch, spectral shape, onset slice and melbands to gain a wide and rich image about the audio that is being played. He formats all this data into three messages that are sent over OSC using the udpsend object. We note an interesting use of the melbands object to “cheat into being a bark array [and another instance with] 40 bands as a fake FFT”. He explains that working with actual FFT gives us far too much data, and as a general principle, it is important to retain the idea that the human brain and human eyes can only take in so much data at once. Indeed, he explained that “eyes can only update 24 times per second, so things don’t need to work at audio rate for it to be meaningful to what we see”. He packs most of his analyses together, and keeps the number of messages that he is sending over OSC low.

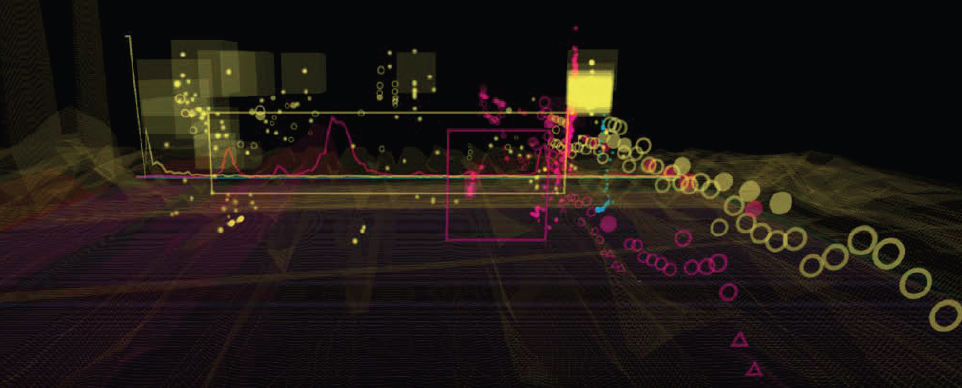

UniSSON Unity UI Waterfall display and particles showing pitch/centroid, amplitude and spectral flatness.

We have provided a number of C# scripts that are used on the Unity side of things, which is Unity’s native coding language. The primary script is Rawlinson’s OSCReceiver.cs script which receives all of the information sent from Max, cooks it and makes it available in Unity in a very modular way: “this is the script that grabs everything, holds it in a single place, then other things grab them”. We have provided two examples of scripts that will take this information and create elements within the environment: ParticleCreator.cs and ArrayFreqAmp.cs. UniSSON will soon be publicly available to download here where you will be able to play with the full array of different elements. The OSC receiver also keeps a rolling record of the previous 128 analyses it has received, allowing Rawlinson to make things like heat maps which display tendencies over time. An inexhaustive list of the various elements is:

- A line-based display of things like the most recent incoming FFT values.

- A scrolling 3D waterfall spectrogram.

- Scrolling particles showing a view of onset, monophonic pitch, amplitude and spectral flatness, or scrolling particles for Mel or Bark frequencies (‘barkticles’).

- Particle display of mid-term activity providing an indication of gesture.

- Bar display of Mel or Bark based values.

- Particle clouds of longer-term activity.

Again, the system is very modular, and any combination of different visualisation elements can be turned on or off at any moment. Rawlinson also demonstrated the importance of the camera view in the 3d space, for example the large difference that is achieved between a diagonal view such as that seen in the image above, and a more linear view such as the one seen below which resembles much more something like a piano roll.

UniSSON Unity UI ‘Piano-roll’ view of particles showing pitch/centroid, amplitude and spectral flatness.

Rawlinson explained that when Murray-Rust visually dropped out of the performance, he was still able to follow what he was doing thanks to this visualisation. Indeed, during the performance it is very much possible to intuitively read many of the microscopic and macroscopic gestures that are happening at different timescales in this ever-developing visualisation. In an article written about the software, Rawlinson and Pietruszewski explain that the software was developed in the goal of aiding a number of different musical metrics:

- Do players feel as if they have an improved sense of who is doing what?

- Do players feel as if the visualisation helps prompt decision about what to do next?

- Do players feel that the interface reflects their contribution and structure musical flow?

- Do audience members feel the visualisation aids their attention to sound?

- Do audience members get a sense of who is contributing particular types of sound?

- Do audience members find that there is still room for surprise and delight with these visualisations?

In any case, this performance was a real test for these first three metrics, and for Rawlinson it was a success: “I was still able to see [Murray-Rust] active in the visual, and that really helped me understand, and I did find myself synchronising to what I was seeing and hearing […] Dave’s visual stream helped me to understand the kinds of things that he was doing, and when he might do them”.

Conclusion

Raw Green Rust proposes a complex and fascinating musical and visual ecosystem. The three musicians are inherently interconnected, however, in contrast to a project such as Alice Eldridge and Chris Kiefer’s Feedback Cello system, they remain three disparate musicians who are pushing and pulling against each other – working towards a common goal yet taking any opportunity for mischief. Here, agency is purposefully undermined, they experiment with techniques to inherently reconfigure the way in which they approach improvisation and performance with a common setup designed to rewire their very brains. There is also a real sense of spectacle and communication between themselves and with the audience – we are invited to inspect their bodily movements and run along with them in the interconnected sonorous web that is in constant evolution. All of this makes for a unique and intriguing laptop improvisation performance.