Sound Into Sound

In this article, we take a look at the work Rodrigo Constanzo did for the project and explore how he used the FluCoMa tools for his corpus-based music making.

Rodrigo Constanzo

Introduction

Download the demonstration patches for this article here.

Today we’ll be looking at some of the work that Rodrigo Constanzo did for the FluCoMa project. We’ll notably be exploring the ways in which Constanzo performs real-time sound matching using audio descriptors. This is an element that he has explored before – we’ll examine how he approached this idea in the past, and how he used the FluCoMa tools to achieve this in his piece Kaizo Snare. As with all the ”Explore” articles, there is a series of demonstration patches that can be downloaded and interacted with if you wish to explore the inner workings of the software.

Constanzo is a great self-documenter of his work. On his website he writes about his various projects, and the work around Kaizo Snare was recounted in an extensive post which can be read here. This post goes into much detail on many aspects:

- The importance of turntablism gestures and techniques in the piece.

- 3D printing, Arduino development and the physical development of various objects used for the piece (crossfader, solenoid robots, snare mount, microphone holder, pedal).

- The trade-offs between accuracy and latency and the ten-year search for good onset-detection.

- Explorations with various sample libraries, crotale timbres and found objects (notably combs).

- Some of the “failed experiments” and approaches that didn’t make it into the final piece.

Despite some inevitable overlap, the goal in this article is not to restate what has already been said. Here, we shall explore two aspects which are perhaps covered to a lesser extent in his article:

- A close focus on some of the inner workings of the patch (illustrated through the example patches).

- A broader perspective on “corpus-based musicking” in general in Constanzo’s work.

We shall take look at some of Constanzo’s previous projects that incorporate some similar techniques to those used in Kaizo Snare; have a look at how things work in Kaizo Snare and how it differs from previous projects; and finally open a broader discussion on what appear to be some of the fundamental aspects that are present in his practice, and how they may inscribe themselves into his wider aesthetic project.

Kaizo Snare was premiered at the first FluCoMa concert at Bates Mill Blending Shed, 21st November 2019. The stage setup appears quite simple: Constanzo is behind a kick and snare drums, with a computer and assortment of objects placed discreetly on a table next to him. As soon as he begins playing, we immediately understand that this is no simple drum solo. We recognize that Constanzo is interacting with the snare drum with his left hand as if it were a turntable, and with a crossfader with his right hand. Very soon we begin to hear sounds that go far beyond the instruments we see on stage: clangings and impacts of a variety of metallic objects.

All of Constanzo’s gestures seem perfectly controlled: there is a striking sense of precision in his rapid hand movements and the sharp cuts heard in the sound. He progresses through the piece, experimenting with different objects upon the snare surface and his condenser microphone: a felt pad, crotales, combs… Twice we are struck as suddenly small robots hidden around the audience begin striking crotales, adding to the landscape of enticing pops, cracks and strikes that Constanzo is masterfully directing. From 8:50 onwards, the piece culminates in a series of gut-wrenching gestures that seem to emerge from a stretched-out, strained melody that is pulled from resonating bassy gongs.

It’s a truly remarkable piece. We are deceived by the seemingly simple setup: the sounds and gestures made on the snare surface are being extended, prolonged, and exploded-out into a whole other universe of noises. Let us take a closer look at this piece, and Constanzo’s work in general.

Previous Projects

Constanzo has had formal training as a pianist, guitarist, and percussionist. He is somebody who thinks a great deal about the physicalities of the objects he uses to make music, illustrated by some of his remarks concerning the differences between guitar and piano: “I spent a long time playing guitar which is very physically sensitive to regurgitation. On a piano, if you play in different keys, things are different – you learn patterns and behaviors but they don’t become so engrained, whereas on the guitar, different keys are the same – so it lends itself more to regurgitation”. He explained that on guitar, “licks just start coming out”, and that he felt that he needed to find strategies to avoid that kind of phenomenon in his practice. This already gives us a great insight into his practice: most of his work is indeed improvised, and most of his recent work sees him occupying the position of a “percussionist” in a very broad, contemporary sense.

We shall return to this, but an important idea in his practice is that what he wants is not what he wants. This seemingly paradoxical project is a fundamental desire that drives many aspects of his work. This is something that he queries in his relationship with traditional acoustic instruments: repetition of licks and engrained gestures is something to be avoided. He will strive to create situations which subvert his own expectations, his own habits and practices. Symptoms of this could be the turns towards percussive practice and the corpus-based extension of it that we shall be looking at today.

Much of Constanzo’s work can be traced through the various softwares that he has made available. In this first example, we see his Cut Glove software being used to transform the signal of a double bass (there are also other examples with a snare drum and a saxophone). One of the first things we notice, both in the presentation of the example video and the screenshot of the patch below, is the care and effort Constanzo puts into the presentation of his work. This could go beyond simply making things easy to use for other people. In his “Traces of Fluid Manipulation” talk, Constanzo talked about the naming of certain parameters of his Confetti Max for Live objects, explaining that it is often “useful to have things wrapped-up in a metaphor”. We often remark the playful naming of his modules and parameters: Cut Glove, C-C-Combine, The Party Bus, Karma~… A refreshing change from some of the stark naming conventions one can be accustomed to with audio plugins.

An overview of the Cut Glove instrument by Rodrigo Constanzo.

As we hear in the example videos, and as we see in this image, Cut Glove is a live-sampling instrument that is built around a looper external that Constanzo made karma~ and designed to be interfaced with via an Xbox 360 controller. If you wish to read more about it and its development you can read Constanzo’s in-depth blog post about it. We see and hear that there are a multitude of effects and playback methods which transform the recorded sounds a great deal. One interesting point to notice here and to think about ahead of Kaizo Snare: these live-sampling operations operate on short, rolling buffers of things that have happened very recently. This is a notion that shall be recurrent in some form across Constanzo’s coding – indeed, despite the apparent ‘real-time’ nature of his practice, much of the processing techniques are happening on recorded audio, albeit in very small timeframes.

The extraits heard with Cut Glove set the scene for the kind of practice we see in Kaizo Snare: an acoustic instrument that is processed by the electronics: the resulting sound being some mix of the two. This will be recurrent in other works. With Cut Glove however, there is no use of external corpora – the only actual sound source is the acoustic instrument, and therefore it retains somewhat of a strong identity. There is no doubt that here, the acoustic instrument is a source that is being modulated. This is a dynamic that we shall return to later.

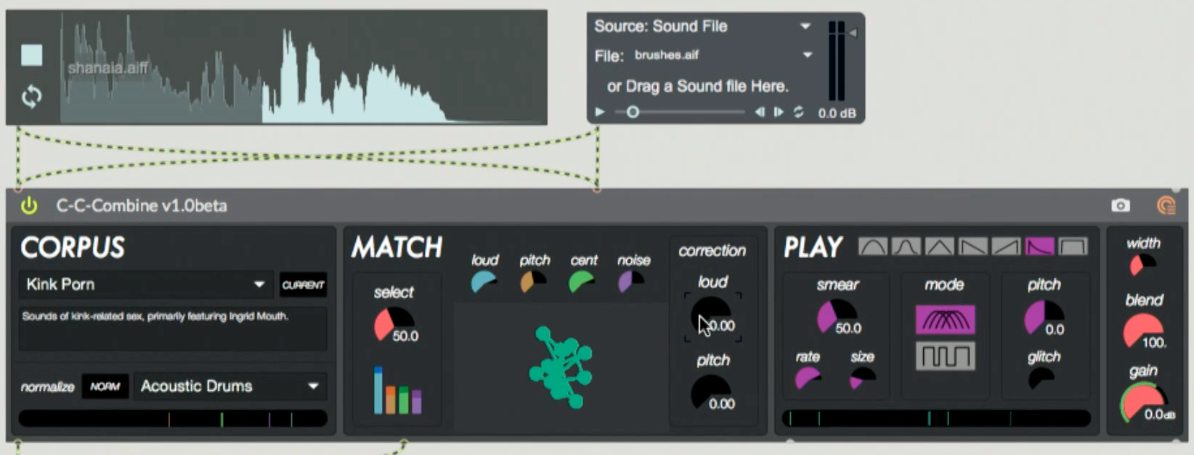

Now let us look at an example of software which directly addresses the question of corpus-based musicking. Constanzo describes C-C-Combine as a “corpus-based audio mosaicking application”. The premise of the software is to be able to “play anything with anything”: in the example video above we see an example of drums playing an electric guitar, a piano playing glitch drums, a contact mic on a canvas playing a corpus of data-derived sounds and a saxophone playing circuit bending sounds.

Constanzo presented this software at the first FluCoMa plenary as part of his artist presentation. This is a ‘real-time’ implementation of concatenative synthesis, which essentially works in the following way: every so often (by default 10ms) the a chunk of incoming audio is analyzed (by default 40ms). Constanzo looks to find the mean, min and max values of the following audio descriptors: loudness, pitch, spectral centroid and spectral flatness (what he calls noise). He then searches a database of pre-analysed audio and looks for the slice of audio that closest matches these values, which will be played in its place.

A shot of the C-C-Combine patch in action.

There are various ways of varying this process:

- Playback can be aperiodic, so that slices of varying sizes are heard. One can also change the length of grains.

- Corrections to pitch and loudness can be applied, meaning that the pre-analysed audio material will be modified to closer resemble the incoming data.

Depending on different parametric settings, the resulting audio can vary from a flow of periodic grains built form an external corpus that closely resembles the incoming audio, to a chunky, ‘Oswaldesque’ mosaique of sources.

To return to the question of source and modulation, again we see here that there is a clear directionality in this dynamic – albeit to a lesser extent than the previous example. There is a clear source, however what is being heard is indeed the external, pre-recorded corpus. In terms of the question of surprise and subverting expected relationships, the sounds that one provides for the system are indeed transformed in unexpected ways: especially in a ‘chunkier’ configuration, the plugin will spit out slices of audio that stray far from the original source – however the stream of audio which is the essence of concatenative synthesis still somewhat stifles the agency that the pre-recorded material could have. It is still ultimately a shadow of what is being put into it – there is an unavoidable dynamic of imitation.

In Kaizo Snare, Constanzo uses many of the same techniques, but in a configuration that is very different. Let us now take a look at what is happening in the patch in terms of audio matching and pre-recorded material.

Audio Matching in Kaizo Snare

The reader must note that Constanzo was a part of the first cohort of musicians that were commissioned to create a piece for the FluCoMa project, and some of the tools which are in the toolbox now were not available during the development of Kaizo Snare. Essentially, Constanzo used some of Alex Harker’s externals, notably entrymatcher~. In the example patches, this has been replaced with objects from the FluCoMa toolbox, notably fluid.kdtree~, as they essentially perform the same task.

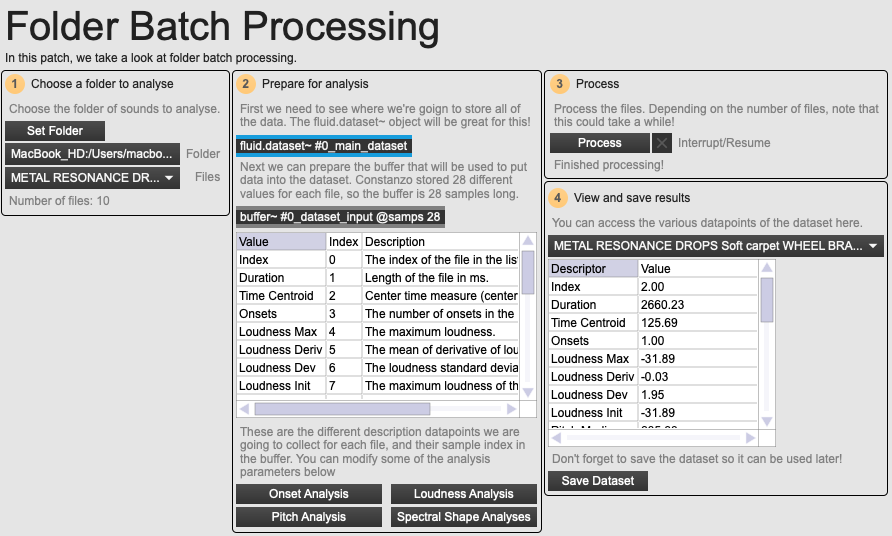

An overview of the folder batch processing example patch.

As illustrated in the example patch O1 Folder Batch Processing, Constanzo pre-analyses corpora ahead of time. Unlike in C-C-Combine where the pre-recorded corpora are long continuous files of audio, here Constanzo uses more traditional sample libraries where each sample is a separate sound file. There were a number of different sample libraries:

- A commercial sound library of metal resonance sounds (various metal objects being dropped and impacted with various objects and against various surfaces).

- A small library of gong samples.

- A collection of crotale recordings.

As we shall discuss below, each of these different corpora will serve different purposes in the patch. Note that we are obviously not able to distribute these libraries with the example patches, so it will be necessary to find your own sample libraries if you wish to try things out.

Demo of the metal resonance sample library

Constanzo collects a total of 28 different audio descriptor statistics for each file. Note that these all correspond with the descriptors that he used for C-C-Combine: pitch, loudness, spectral centroid, and spectral flatness: he used the FluCoMa fluid.butpitch~, fluid.bufloudness~, and fluid.bufspectralshape~ to collect these values, and fluid.bufstats~ to derive statistics from them. He also collected a few other values, such as the number of onsets in a file using fluid.bufonsetslice~ (with a particularity for the metal library – he passed the name, and if the name contained the term “drop” the file was processed as having at least 2 onsets) and the time centroid using the irstats~ object from the HISS Impulse Response toolbox (a way of deriving the time of the centre of energy). Note that, as we shall see, Constanzo will not end up using all of these values, but when batch processing, we may as well collect more values than we’ll need so that we can have a choice later on.

The 28 values for each file are stored in a fluid.dataset~ (at the time this object was not available, so Constanzo stored his data in text format in a coll). Once batch processing is finished, the contents of the dataset can be saved as a json file and used again later. Up to this point, we are dealing with essentially the same process as C-C-Combine.

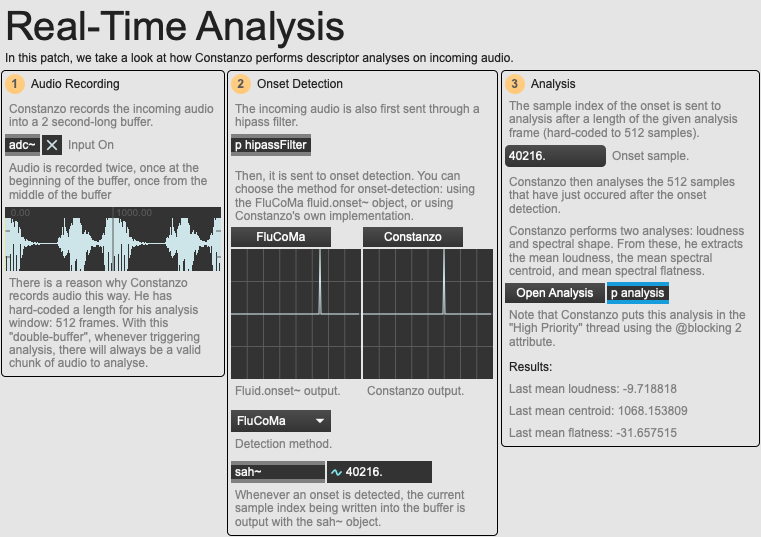

An overview of the real time analysis example patch.

Next, we can take a look at the 02 Real-Time Analysis example patch. This is where a first big difference will be happening compared to C-C-Combine, and one that will have significant aesthetic importance regarding the piece. Analysis of the incoming audio is no longer happening systematically every grain: here, analysis only happens when an onset is detected. Once this onset is detected, Constanzo attempts to gain an idea about the aspect of the sound that caused it. As you can imagine, this is quite a complicated question, as he is trying to get this information in ‘real-time’ – but how can you gain information about a sound while it’s being played?

For this reason, Constanzo defines an analysis window of 512 samples (which comes to about 11.6ms). Once the onset is detected, he waits this amount of time before analysing the proceeding audio. This, combined with the time that it takes to analyse the piece of audio, seems to strike a good balance between understanding the aspect of the onset, and retrieving the information quickly (note that, the @blocking 2 parameter for the FluCoMa tools was actually developed in answer to Constanzo’s desire for lower latency – it is a mode for Max only that puts the processing of an object into the scheduler thread, making it of highest priority: naturally, during development this mode was referred to as Rod mode).

It must be noted that this balance, this “sweet spot” was developed around a specific type of gesture, a specific type of sound. With the example patches, we have provided an audio file of the type of signal that is being processed during the piece: a dry recording from Constanzo’s condenser microphone of the snare surface during the performance. As you can observe with the test patch, on each onset detection, Constanzo retrieves the moment in the rolling buffer that this occurred, and the descriptor data from the subsequent 512 seconds:

- Mean loudness.

- Mean spectral centroid.

- Mean spectral flatness.

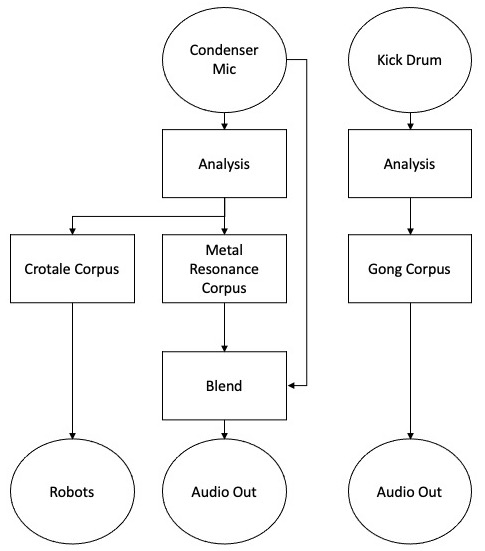

An overview of analysis, matching and corpus routings in Kaizo Snare.

Constanzo will then take this data, and similarly to C-C-Combine, use it to find matches in the pre-analysed database of sounds derived from the batch processing. In this diagram we see the ways in which mapping broadly happens between input material and corpora (this is subject to mode changes, and there are other processing elements in these paths, some of which are discussed below). As you can see, the data from onsets detected in the real-time content from the condenser mic will be used to query and match sounds from the metal resonance corpus, and the crotale corpus; onsets from the kick drum will query sounds from the gong corpus.

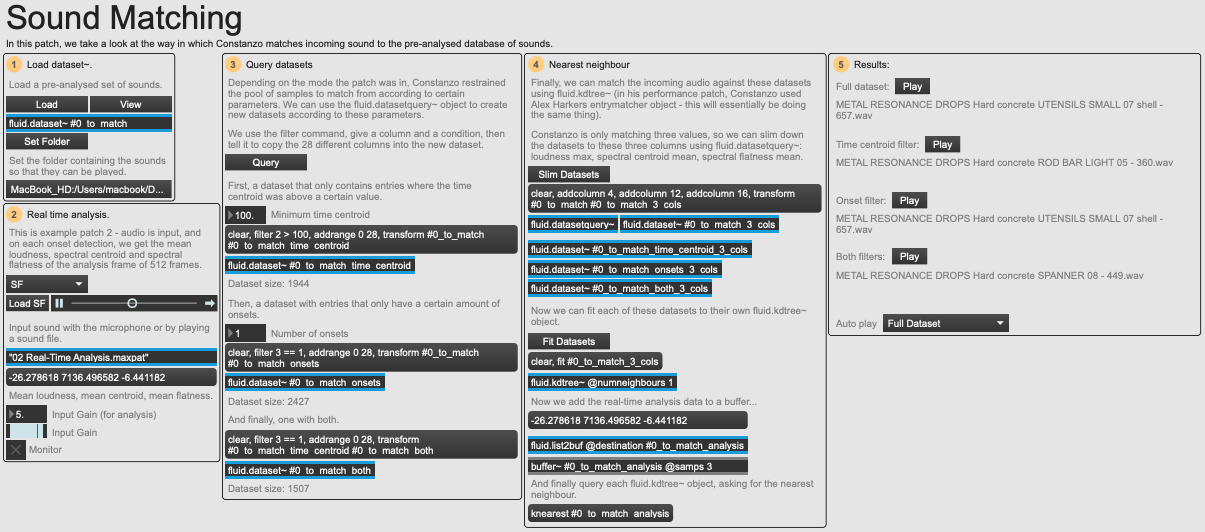

An overview of the sound matching example patch.

In example patch 03 Matching, we see an example of how this querying and matching process works. First, the user loads the dataset of the folder of sounds they wish to query that was made using the 01 Folder Batch Processing patch, then sets the input source (here, we are using the recording provided of Constanzo’s condenser microphone). Depending on different modes, Constanzo first performed some filtering of his query database:

- One filter that removes any entries with a time centroid below a certain value.

- One where the number of onsets has to be equal to a certain number.

- One where both of these filters are applied.

Here, we have used fluid.datasetquery~ to perform these operations and create a new fluid.dataset~ for each filter.

Then, we can use fluid.kdtree~ to get the nearest neighbour to our onset. First, we are only query three values: the max loudness, mean spectral centroid and mean spectral flatness. For this, we can again use fluid.datasetquery~ to slim down the datasets to the size we need. Then, it is simply a case of fitting a fluid.kdtree~ for each dataset, before we are ready to retrieve the nearest neighbour for each onset. As you can see in the example image, each filter may give different results. Here, we have put it into auto play mode on one of the filters, so that we can hear in real time the input source and the matched sample.

This is how the matching works for the metal resonance corpus. There are a few differences in other case, for example in the kick drum matching, the chosen sample has its pitch corrected, similar to the correction that occurs in C-C-Combine. Indeed, this matching essentially functions in the same way as C-C-Combine – the main difference will be in the way the chosen queries are allowed to sing out.

There is no continuous flow of concatenative synthesis. Depending on the signal patch, the chosen samples will play differently:

- In the case of the metal resonance library, the sample will play once, and be subjected to several processes, notably a wavefolder module (see below). Its signal is then blended according to the crossfader with the raw (processed) signal from the condenser microphone. This way, Constanzo is constantly making gestures which will chop between the original sound source and the sample it triggered.

- In the case of the crotale corpus, the actual samples are not played, instead they trigger the solenoid robots to which they are mapped. These robots were distributed around the audience and tapped on their respective crotales with either a metal or plastic rod.

- Finally, the gong corpus is allowed to play out without any interruption – a corpus which is notably comprised of relatively long sounds. They are, however, corrected in pitch to match entries from a pool of pitches which is collected from the condenser mic material at certain moments (Constanzo tended to trigger this when he was using the comb).

One of the solenoid crotale robots.

Before continuing to talk about these configurations and how they may insert themselves into Constanzo’s wider aesthetic project, let’s take a quick look at some of the processing that happens within the patch, and see how the material that we hear is transformed.

Audio Processing

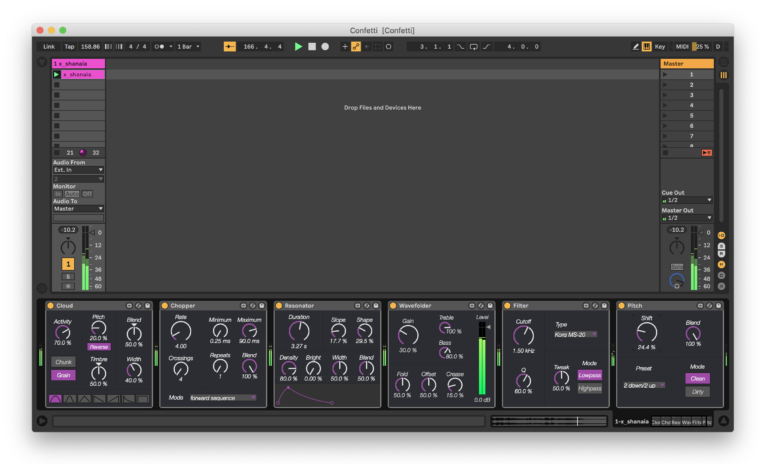

Constanzo is clearly attentive to the aspect of the sounds that are emitted from his system: the presence of various filters, normalisations and clippings attest to the careful sculpting of the audio spectrum (due to the nature of the instrument, this is also necessary in order to control feedback to which the system can be prone). Beyond this, there are a few notable effects that seem to play an important role in building the sounds that are heard. These have been wrapped within Max for Live modules, and Constanzo has since released them as a package of modules called Confetti.

Constanzo's Confetti modules in Ableton Live.

As we can see in the image of the Kaizo Snare parent patch in presentation mode, Constanzo uses 3 of these modules: Cloud, Dirt and Wavefolder. They take up a large amount of space on the parent patcher, which indicates that they must me of some importance. The Dirt module (implementing two different types of distortion) is used to process the raw condenser microphone signal. The Wavefolder is also is also used for this, and on the playback of the metal resonance corpus. Finally, the Cloud module is used on the blend of metal resonance and condenser microphone signal. The Cloud module is particularly interesting, and again brings up questions concerning ‘real-time’ processing and Constanzo’s approach to this. Let’s take a closer look.

The Kaizo Snare patch in presentation mode.

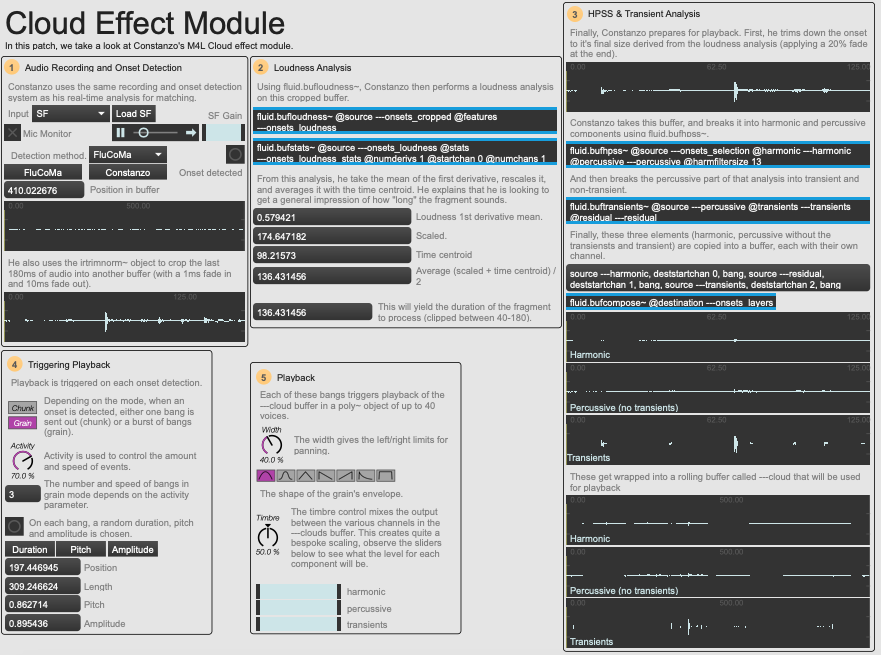

As you can see in the image below, example patch 04 Cloud breaks down the Cloud module, explaining what is happening. Constanzo describes the process as “a real-time granulator that is triggered by onset-detection such that whenever an attack is detected a new bit of audio is written into a circular buffer and bits from that rotating pool of attacks are played back. So, it’s kind of like separate record and play heads for a looping delay that only operate when an attack is detected”. Indeed, the effect triggers in the same way as the audio matching described earlier: on the detection of an onset, subsequent audio is recorded into a buffer.

An overview of the Cloud effect module example patch.

Next, Constanzo trims down the buffer to 180ms, and uses fluid.bufloudness~ and fluid.bufstats~ to try and get a general impression of how ‘long’ the sound is. He does this by taking the mean loudness of the first derivative and averaging it with the time centroid. He uses this value to get the duration of the fragment of sound that he wishes to process. Then, he uses the fluid.bufhpss~ object to split the fragment into its harmonic and percussive elements. He then takes the percussive part, and further splits this using the fluid.buftransients~ object. Effectively, he is left with three layers which will be blended between when playing back the sound (harmonic, transient, and the percussive without the transient).

Playback happens by default in bursts, with a random pitch and amplitude for each occurrence. The Timbre parameter is the “useful metaphor” that Constanzo uses to hide the non-linear blending between the different layers derived from HPSS and transient decomposition. Once again, despite the apparent ‘real-time’ nature of Constanzo’s musicking, we see that he resorts to offline processes. Constanzo wishes to deal with actual sonorous objects, not a continuous signal flow – he does not deal with the mapping of a constant measure to a certain parameter, but the measure of full events: onsets, and their resonance. This means that he finds himself constantly riding the line between real-time analysis and analysis of sounds that have occurred in the past. This metaphor can be prolonged to the duality in his work between real-time playing and pre-recorded material.

Sound into Sound

We see that, in Kaizo Snare, Constanzo has developed a particularly delicate relationship with pre-recorded material. As we have seen, and as can been seen in his explicative video below, the relationship between live, real-time audio that is emerging directly from his gestures and the pre-recorded sounds is much more complicated that a simple match-and-replace. Here, the dynamic between source and modulation seems to break down. Yes, form a technical point of view, we know that it is the condenser microphone signal that is being decomposed and matched to the pre-recorded sample library, however the configuration of the system seems to dilute this notion somewhat.

Consider the synchronisation in Constanzo’s gestures: the left and right hands are clearly working together. Constanzo talks in his article about the importance of the turntablism techniques that he has applied to this setup – indeed, he even went so far as to take lessons with a professional. In turntablism, and in Kaizo Snare, it seems that one hand cannot live without the other. There is an immediate and inextricable relationship between the two. The left hand, constantly creating material and triggering samples, is constantly modulated by the right, leaving no conceptual space for source and modulation. Constanzo truly seems to merge present and past in this configuration of hands, crossfader, condenser microphone and snare surface.

Indeed, the role of the sound he is producing becomes expanded: is the signal that it is providing sound material or control data? Evidently, the answer lies as a balance between the two. This is something that we often see in musical systems that employ machine learning techniques: for example, the same notion is discussed in the “Explore” article about Alice Eldridge and Chris Kiefer’s piece. In the case of Eldridge and Kiefer, this relationship is perhaps more explicit, and somewhat part of the nature of a feedback instrument. In the case of something like C-C-Combine, the balance of this relationship is very strong: the incoming audio is clearly a driving control signal for the plugin. However, here this balance is constantly slipping around, rendering the mix of signals ambiguous. This dual status of control gesture and sound in the context of machine learning-assisted musicking is a fascinating question.

Let us now try and think of these ideas in the context of Constanzo’s wider aesthetic project. Across the various interviews, workshops, and plenaries that Constanzo attended in regard to FluCoMa, there was one aspect that kept on coming back: the desire to get what he does not want. This joins back with the idea discussed at the beginning of this text of wanting to subvert habits, the expected. He seeks to be surprised.

Of course, Constanzo does not blindly want to jump into a system and have absolutely no control over what happens – indeed, he does want what he does not want. This is what makes the design of this kind of system so stimulating and complicated. Constanzo has to navigate this spectrum of risk. He described it as being adjacent to danger: “if you’re skydiving, you don’t want to die, but if there’s no danger, you’re not skydiving!”. In the case of technical programming, this is expressed through these kinds of systems which will always return an answer to a query – most of the time the result will probably be expected, however there is space for the system to return ideas that will surprise, stimulate, and push you.

This is a driving factor behind much of his work. For example, here, in Rhythmn Wish, we have a chaotic situation which has an element of danger: the CD player can break in a way that is not useful for the performance. Constanzo explained that this feeling of danger is something that he looked for in an improvisation system. These concepts of danger, risk, and surprise are very important to him, and are perhaps ways in which he amplifies what are, for him, the most interesting inherent properties of music itself:

one of the things I find most exciting about performance, and music in general, is the unknown aspect to it. The surprise that comes from the linear passage of time, where each new moment has yet to be determined. […] I like to swim in this place, that tiny moment between the past and the future

Improvisation is a particular kind of musical practice, where these aspects are notably experienced not only by the audience, but also by the performer. The exploration and insertion of risk and danger into his improvisation systems can only serve to boost these feelings.

Conclusion

As with all the “Explore” articles, there are many more things that could be discussed about this piece. Again, we recommend that you have a look at Constanzo’s autobiographical article about the piece, where he goes into detail about many of the aspects that go beyond the use of the FluCoMa tools. In this article, we hope to have portrayed how the FluCoMa tools have helped Constanzo realise and develop some of the fundamental ideas behind his practice.