Blank Slate Confrontation

In this article we take a look at James Bradbury’s creative work and his bespoke way of using the FluCoMa command line tools within his own Python environment and Reaper.

James Bradbury

Introduction

In this article we’re going to taking a look at some of the creative work that James Bradbury has done using the FluCoMa tools. You may be familiar with Bradbury’s name, as he has been close to the project for a while: he has been an active participant on the FluCoMa discourse for a very long time and joined the project in 2021 as a research fellow. He has been behind many of the tutorials and project documentation, and naturally he knows the toolkit and its workflows like the back of his hand! You may also know him for some of the valuable contributions he has made for broadening the breadth of the tools by bringing them to the DAW Reaper and to Python (we’ll look at this in detail below). The piece we shall be examining today is an album he released in 2022 on 時の崖_tokinogake: Interferences.

Interferences is split into two parts: G09 and P08. G09 follows the tumultuous path of a constant hiss which lurches and snaps sporadically into different states of being. These vary from chaotic hives of activity to pulsating swells of noise. P08 shares a similar sound world but is structured by successive emergences of tones and noisy harmonies. At first these are delicate and veiled in a muslin haze; before soaring into piercing clarity, and finally crumbling into wretched, sedimentary edifices that engulf us completely. Both parts share a unique sound world that goes beyond synthetic electronic sounds – there is a stark rawness that, on the one hand, entices by the delicate structures that are just hidden from comprehension; but also, disquiets by its indifferent ferociousness. Bradbury has found a balance between proposing a structured and gestural snapshot into these wild ecosystems and retaining a tangible trace of their incontrollable nature.

Today we shall start by looking at some of Bradbury’s previous work and the context from which this piece emerged. Then we shall take a look at the tools that James developed around and on top of the FluCoMa tools: notably his Finding Things In Stuff (FTIS) library for Python, and the ReaCoMa tools. Then finally, we shall take a closer look at some of the specific process he deployed for structuring his pieces and aiding his compositional practice. Many of the subjects we shall be discussing today are also discussed in much detail in his PhD thesis which is online and remarkably easy to navigate – we shall try and avoid simply repeating everything that has been explained there, and propose a broader view on Bradbury’s practice.

Endless Corpora

Before looking at Interferences, let’s begin by taking a look at some of Bradbury’s previous work to get an idea about the kind of sound world he likes to inhabit, and the kind of processes he likes to deploy. Let’s first take a look at the types of sounds that Bradbury likes to play with, and how he obtains them.

As you can hear in the two tracks on the album, Bradbury enjoys harsh, noisy electronic sounds. However, there is a certain quality about them that sets his music apart from other electronic musics – there is a certain rawness about them, a wildness and mystical energy. The reason for this, in this author’s opinion, is because they are not human engineered. Bradbury explores ways of collecting large collections of sounds which are biproducts of other objects, they are the natural sonification of digital or mechanical devices which have been bent or ripped into sound. This gives the sounds in his music a really quite beautiful, but unnerving nature.

For example, in a previous EP Reconstruction Error, the sounds that are heard are fragments of raw data on his computer that have been converted into WAVE files. This was achieved with Bradbury’s tool mosh, which is his implementation of audio databending – taking data that was not intended to be decoded as audio and transforming it into a format that can be read as such. This essentially works by taking raw data and appending at WAVE header to the beginning. Below we can hear an example of a GPU Driver file that has been transformed into a WAVE file using mosh.

The source audio for Interferences was collected in a different way, but following a process which follows similar ideas of hacking, bending and hijacking electronics and drawing audio from them. He used “an induction microphone to record devices throughout the home wherever I could find them. [I then generated] a corpus by manipulating those devices in real time while recording: for example [on a phone] turning the wifi on and off, putting it in airplane mode”. In both Reconstruction Error and Interferences, the audio is some kind of biproduct of something else, it is an inspection of a sound world that was never meant to be heard, that exists on another plane of existence that we can tune in to through different technologies. These are sounds that emerge from invisible systems; systems that were forged from human hands, but are so far removed from the hands of their creators that they have no hope of understanding them.

When collecting the sounds, Bradbury looks to find variation in his sources, not build things up from nothing. The sounds pre-exist, and “the conceptual boundaries of the corpus are endless”. These kinds of musical ideas can be found in the works of people who explore ideas of fragmentation and open works; pursuing ideas of catching on to a moving train, and leaving it without stopping at a station. These are not samples of a thing; these are fragments of worlds that have no beginning or end, it just so happens that at one point someone pressed record, and at another they stopped recording.

For Interferences, Bradbury ended up with around 20 hours of recordings. For Reconstruction Error, he scraped the entire contents of his hard drive to create a corpus. It would be interesting enough (if a bit long) to hear these recording as they are collected, however Bradbury takes them further and draws from them the gestural pieces we hear as final results. Part of his art is not only finding the parts of these collections of sounds that are interesting enough to merit our listening, but also to find spaces in these sound collections that complement each other and find points of interface between worlds.

So, the starting point of his pieces are these collections of sounds. The question is how to deal with such vast collections of data. As the reader shall undoubtedly be aware, one of the premises of the FluCoMa project is to deal with this very question. We shall now examine how Bradbury not only used the FluCoMa tools to find the things that he wanted in these collections, but also interrogate them in a way that allows him to forge artefacts that will form the very basis of his work. The idea will be to “work subtractively from a corpus”. This is a way of getting away from the eternal fear that haunts many artists: the blank slate, blank patch, project, session… Is it possible, with corpus manipulation tools, to develop a strategy that removes this question?

Finding Things In Stuff

To begin to answer this question, let’s first look at Bradbury’s primary tool for corpus manipulation. The core of many of Bradbury’s tools are the Command Line Interface version of some of the objects in the FluCoMa toolkit. For those who are unaware of these versions, they are processes that can be run from the terminal on your computer. This minimal interface can turn some people off from using them – indeed, at a first glance it certainly doesn’t seem very practical to use them in this manner. However, one powerful aspect that the CLI tools offer is the ability to access them from a coding language such as Python.

This is exactly what Bradbury has done! The first iteration of this idea is found with his python-flucoma library. With this library, FluCoMa tasks can be performed in a few lines in python, for example, a typical slicing task:

from flucoma import fluid

source = 'path/to/my/source/audio.wav'

ns = fluid.noveltyslice(source, threshold = 0.1)

idx = get_buffer(ns)

print(idx)Or obtain and process descriptor data like this:

source = 'path/to/my/source/audio.wav'

mfcc = fluid.mfcc(source)

stats = get_buffer(fluid.stats(mfcc), “numpy”)

print(stats)This library relies on the subprocess Python module which allows you to run the CLI tools from a Python script. This allows the FluCoMa tools to be used in a clean, easy way within Python, and opens to door to easy manipulation of the subsequent data by any of the numerous open-source libraries that are available in Python.

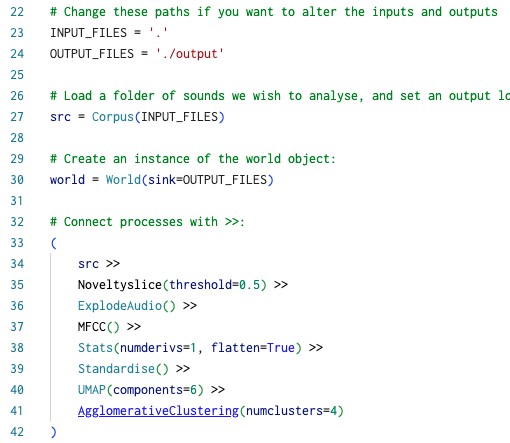

Bradbury further developed this with a library called Finding Things In Stuff (FTIS). An important aspect of this library is the World() class (the choice of term here in regard to some of the ideas discussed above seems quite apt), which allows you to chain different processes together, and also answers a problem that you will have come up against if you have done much batch-processing of corpora in any way: doing the same processes more than once. Using caching techniques, and when operating within the confines of a World(), the library will know if a certain process has already been performed and take this into account. This is the kind of thing that can easily be lost track of when done manually and is all done programmatically with FTIS. Bradbury discusses this in detail in his PhD.

Overview of the FTIS example script.

FTIS allows for many of the FluCoMa-derived workflows you will have come to expect when dealing with large corpora: slicing, descriptor analysis, statistics, dimensionality reduction, clustering (see example script 01 FTIS Example). Bradbury explained that “[with the text-based interface] you get a level of abstraction and composability that you don’t have in Max. It would be like trying to write a patch using thispatcher or something. You can just programmatically generate the things you need and have them know about each other in an automatic way.” As we shall see in the next section, Bradbury manages to compartmentalise his time quite well between coding and composition work and having this stable corpus manipulation environment helps with that: “once you design the system, you don’t have to think about it; you can think about how it works and what it’s doing”.

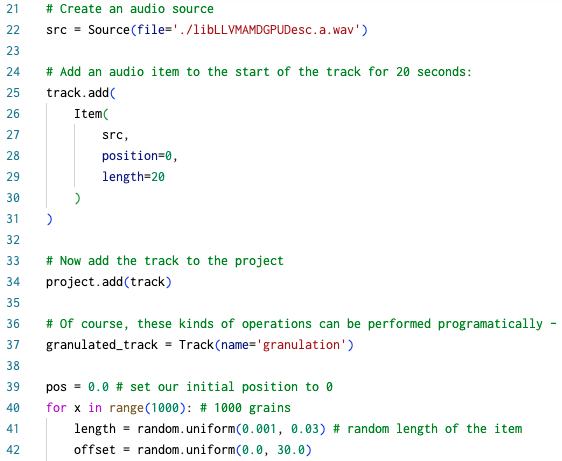

Overview of the Reathon example script.

Again, being a library for Python, it is very easy to integrate this library with other tools. Notably, Bradbury integrates this with Reathon, a library he wrote that allows for programmatic generation of Reaper project files. As we see above and in the 02 Reathon example example script, we can very quickly generate complicated Reaper projects in any number of programmatic ways. As you can imagine, the combination of these two libraries creates an extremely powerful tool that will propose a serious base for answering the problem of the blank slate. Bradbury describes the workflow he will follow as “analysing the corpus with audio descriptors, projecting those many dimensions for each sample into some kind of space, then finding different manoeuvres around that space to create different groups of samples that will inform composition”. What is the nature of these spaces, and what is the nature of the kinds of manoeuvres that he will look to make through them?

Manoeuvres and Space

As stated above, Bradbury gives a detailed account of much of his recent work in his PhD, and there is a full section dedicated to his Interferences project. We highly recommend you go and visit this page. Here we shall be giving an overview of some of the processes from quite a broad stance and offer some critical reflections around some of the things that occurred.

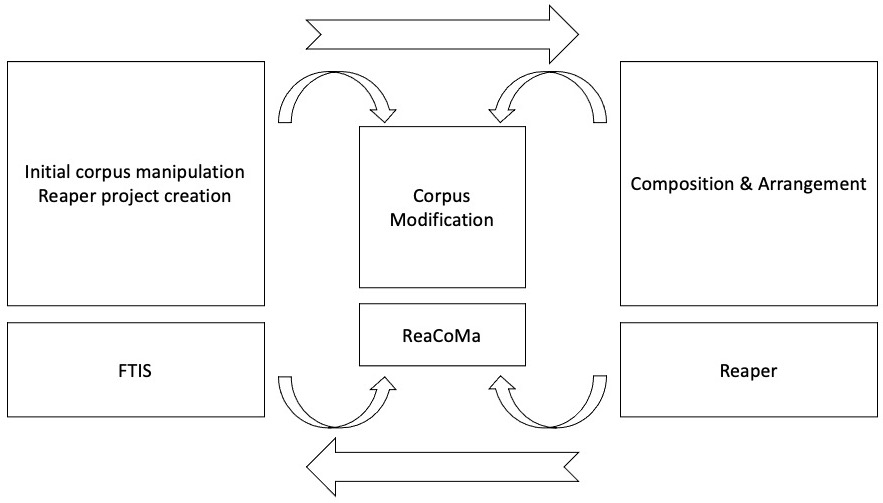

Overview of Bradbury's compositional workflow (01).

Returning to some of the points discussed above, we can synthesize Bradbury’s compositional workflow in the image seen here. Each part of the process has its own associated tool: initial corpus manipulation and project creation are associated with FTIS; composition and arrangement are associated with Reaper; corpus modification is associated with ReaCoMa. Bradbury explained that Reaper “enables me to discard coding thinking; or ignore it for a time. You get a timeline for free, playback for free, state management for free. All these things that allow you to forget about coding and think about sound and how it changes over time”. We see that Bradbury strongly separates acts of corpus management (which coincides with the creation of an initial block for sculpting) and the act of composition, of arrangement and organisation (the subsequent sculpting of this block). These are both musical activities but are nonetheless different in nature.

Bradbury describes ReaCoMa, his implementation of some of the FluCoMa tools within Reaper, as “sitting somewhere between the two […] it allows me to reapproach materials that have been organised [with] resegmentation and processing using decomposition”. We can see this as having more fluidity in his sculpting of the initial block, having the freedom to append more material and not being bound to use just one chisel.

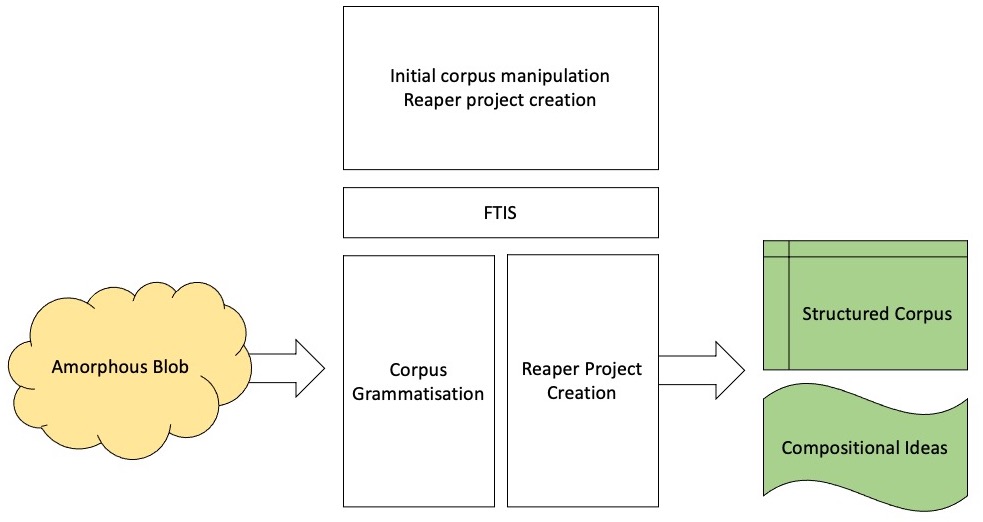

Overview of Bradbury's compositional workflow (02).

Above, we see a further decomposition of the process that falls under the activity around FTIS. Note that, these separations are merely conceptual, and in reality activity tended to shift between different aspects, but it is still important to note these conceptual separations. We see first an initial navigation through a corpus, which will correspond loosely to the grammatisation of a somewhat amorphous blob of sound into something structured by a hybrid of machine and human listening, and something that is very personal and revealing of Bradbury’s musical thought: in his PhD Bradbury uses the term structured listening; and finally the activities that led to the creation of the compositional grains in the form of Reaper projects.

As Bradbury states repeatedly in his PhD, much of the subsequent compositional work (in a more traditional sense of the term) is carried out somewhat intuitively. However – one would be remiss to look at this process as simply generating sound and then intuitively playing with them. Through this process of computer-aided listening and grammatisation of a corpus, compositional principles and ideas emerged which were then explored and finalized intuitively. In regard to the question of the blank slate, we see here that this process not only creates of block of sound from which to work from, but also compositional ideas and the entrances to paths down which one may embark.

Structured listening

As we shall see across many of the processes that Bradbury follows and forges across his practice, he will tend to conceptualise of data in a bipartite manner, structuring his thinking and measurement of things like audio in terms of contrast, and indeed, extremes on continuous scales. This can first be observed in his initial way of approaching the corpus. He explained in his PhD that on his initial, broad listening of the recordings, he loosely identified two states in the material: active and static. These states seem to pertain on the one hand to the nature of the sonic material, but also to the mechanical and physical states of the devices. Note that, Bradbury doesn’t ask the computer to listen to the corpus with nothing to go on at all – he will use this basic, mechanical reality of the source material as a starting point.

Thus, he first asked the computer to perform a segmentation and classification into these two states. As the length of these states across different recordings and devices was very variable, he devised a custom clustered segmentation algorithm (based on an approach by Lefèvre and Vincent (2011)) with the goal of being fairly agnostic to the material it looks to segment:

- Start by segmenting the source into small chunks, the smaller the better.

- Perform audio descriptor analysis and cluster chunks together.

- Finally merge chunks which appeared next to each other and belonged to the same cluster in the source material.

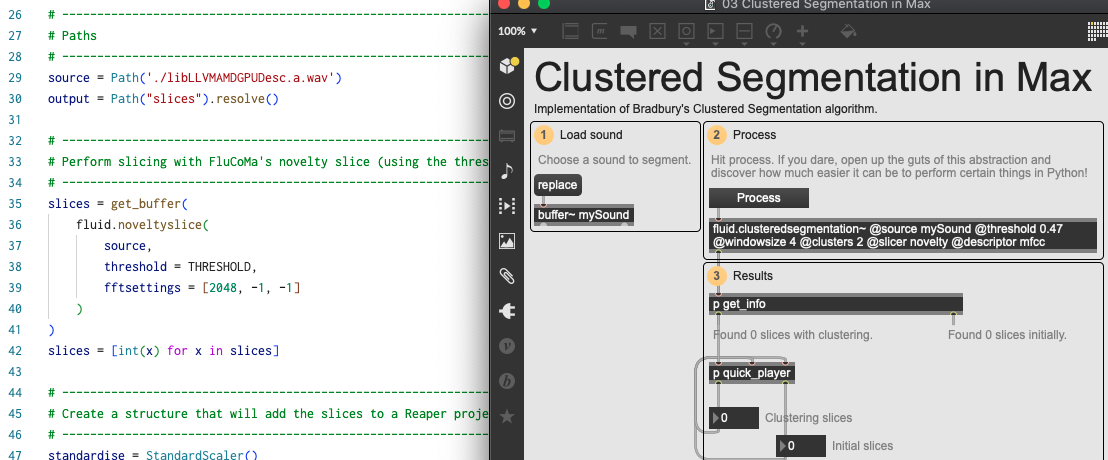

This algorithm was implemented as a slicer in FTIS, but you can see how it works in example script 03 Clustered Segmetation.

An overview of the Clustered Segmentation script and an implementation in Max.

He then took these segmentations and classified them using a spectral flux descriptor analysis. He deemed the results “acceptable” and used them as a base for further experimentation. Especially at this early stage of the process, the goal does not seem to be to gain precise, exact results, but to begin to iteratively and broadly structure the corpus. Indeed, this looseness allows for happy accidents to occur which we shall observe presently.

After this he performed some experiments where, as is often the case in the humanities, the lines between the conceptual separations given above begin to blur. With each experiment he creates a number of sketches and demos which all make for fascinating listening.

One important experiment was to further deconstruct the active state samples “into impulses, utterances, and segments”. He did this in the following way:

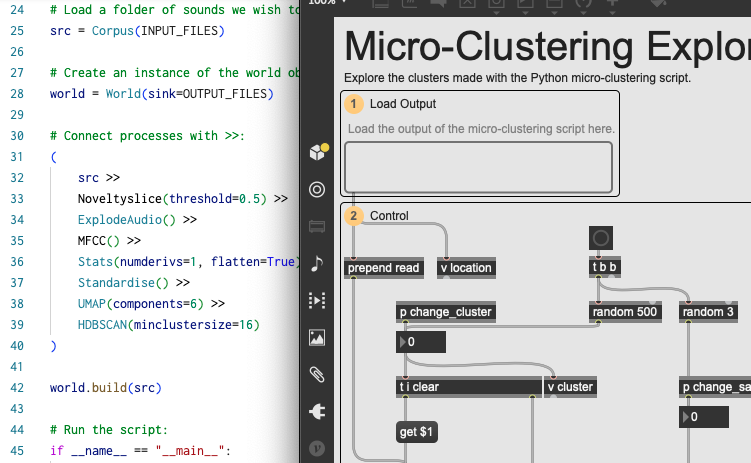

- Further segmentation of the sounds.

- MFCC analysis of the segments.

- Agglomeration using the HDBSCAN clustering algorithm.

He termed this process “micro-clustering” (see example script 04 Micro-clustering). When listening back to the results he discovered that some of the static content had seeped through the cracks and had been treated in this same way with active content. This was something he embraced and allowed to develop into the final piece.

An overview of the Micro-Clustering script and it's Max explorer.

Bradbury performed various other experiments that allowed him to “develop a ‘knowing’ of the corpus […] the more you get into the guts of it, the more you start to see patterns”. At one point in this process, he felt that he’d gained enough knowledge of the corpus to assess that there wasn’t going to be enough variation in the material to give him what he wanted for a whole piece, so he decided to bring in material from the corpus that was used for Reconstruction Error. As we shall see, part of this entailed finding points of interface between the two corpora. The further his experiments continued, the closer he got to the final pieces we hear on the album.

Walking Paths

Let’s examine some of the processes that Bradbury developed that would play a more direct role in the pieces. We can begin with track 2, P08, which we remember was distinctively droney, and had a lot more pitched material than the first track. With this we can examine a strategy that Bradbury developed that simultaneously drove compositional ideas and corpus navigation: that of “anchors”.

He wished to examine the level of variation in the static material he had identified previously. Throughout the navigation phase of composition, three distinct profiles of sounds appeared to him, three sounds which he took as anchors. He wished to create groups of sounds that were similar to these anchors: to do this, he created a 2-dimensional plotting using a UMAP dimensionality reduction of material that had been described using a CQT descriptor which worked well for “showing differences in pitch as well as discerning fine-grained spectral complexity in high frequencies”; and use a KDTree to get groups of nearest neighbours.

This approach is now somewhat characteristic of a typical FluCoMa workflow – see articles on Alex Harker, Gerard Roma and Jacob Hart’s work. One interesting aspect here on the other hand is that Bradbury bypasses the visual element that UMAP reductions are typically associated with and transcribes nearest neighbour searches on critical pre-identified anchor points within the corpus straight into the DAW – into the “same context as the compositional act”. This also means that he is not limited to reducing to 2 or 3 dimensions, and he explained that he would often project to as many as 20. He uses dimensionality reduction in this case to “[make the machine make] more intelligent decisions about how data might map onto perception”.

The content generated from searches within the descriptor-space serve as the base for intuitive composition, creating superimpositions of two types of “anchor groups” he deems perceptibly similar and the other. This served as the very base of the composition, and “longer-form developments were orchestrated as interactions with this layer, either emphasising and adding to it or assuming the role of sonic antagonist”.

The first piece of the album, G09, stemmed from a “strong aesthetic response to a particular recording – the e-reader”. Bradbury stated that there was a particularly strong clarity between active and static states in these recordings, and that they proposed two strong and distinctive musical behaviours: “static content had strong pitched elements that were unwavering in dynamic [and] active content was more gestural and exhibited varied morphology”. In this piece he wished to “separate these two behaviours and deconstruct their relationship”.

An interactive diagram that Bradbury used in his PhD to visualise his compositional workflow.

Again, the starting points of this project were articulated around the contrast between active and static states: the beginning of the piece seeing the static ‘base layer’ being “ornamented with other samples, active states deconstructed to recycle that first material and proliferate over time”. In this piece, Bradbury also made notable use of many of his ReaCoMa scripts, crossing that blurred line between programmatic coding and corpus navigation, and intuitive composition: he resegmented samples, created variation by repeating and duplicating them, and using ReaCoMa’s descriptor-based reordering. Towards the end of the piece the distinction between these two state-materials also blurs. In the final part of the piece, he uses results from the micro-clustering process which he specifically deemed to “border between active and static states”.

We see in both of these cases, that having built up an understanding, a knowing of the nature and aspects of the corpus, Bradbury pursues these avenues to create his pieces. We see that he seeks to expand properties of this collection of sounds, rather just using them as material for other means. Essentially, the piece grows naturally out from the source material. This is perhaps how Bradbury achieves this aspect that we discussed upon a first listening of the album: the achievement of a kind of balance between the wild and uncontrollable world presented by the source material, and the still structured and gestural content of the pieces in their recomposed form.

Despite this, it is clear that the piece would be very different if it were made by someone else. We see the instinctive decision, the instinctive conceptualisation that Bradbury made about the corpus, this idea of active and static states, amplified throughout this whole process. This was the first step on a path that conditioned the entire nature of what would follow. Bradbury’s listening of this collection of sounds is engrained within the compositional process: he is essentially presenting to us a listening of these worlds, his listening of these worlds. I’m sure you would agree that it is an extremely stimulating way of approaching composition, and one that pushes us to listen to his pieces closer and closer, enthralled at the crossroads between these strange autonomous systems, and the composer’s affect.

Conclusion

We have examined how Bradbury has taken the FluCoMa tools, incorporated them into his own distinct workflow, and forged them into a tool that well and truly gives a serious solution to the problem of the blank state. This solution goes further than putting parts of a corpus into a DAW, it is part of a conceptual process that generates compositional ideas through a symbiosis of human and machine listening. Bradbury explained that the ways in which these processes work mean that the tool that is his computer is essentially inseparable from the work. Indeed, it seems difficult to imagine this kind of work being possible without the immensely powerful tools that the computer and projects like FluCoMa can offer.