Data-Driven Musical Interfaces & Live-Coding with FluCoMa

In this article we shall be exploring some of the creative work of one of FluCoMa's core developers Gerard Roma. We shall take a look at his live-coding practice that revolves around visualisations and interfaces built using the FluCoMa tools.

Gerard Roma

Introduction

Today we shall be looking at the creative work of Gerard Roma. Roma was one of the core team members on the FluCoMa project, doing much of the core programming along with Owen Green. In this article, we shall explore the position he occupied as developer but also as musician and creative coder, using the tools to create an interface for live-coding. We shall examine how he performed with this system at the second FluCoMa concert at Dialogues Festival 2021. As with all the “Explore” articles, there is a series of demonstration scripts that can be downloaded and interacted with if you wish to explore the inner workings of the software, in this case written by Roma himself. You will also need FluidCorpusMap to get the examples to work.

The piece The Big Fry-Up begins gradually, Roma introduces us to a delicate sound world that begins distant and murky. In these dense depths patterns and almost-melodies begin to emerge. Elements progressively build up, and at some point, we suddenly realise that things have burst out into a blooming cloud of chaotic noise. Rhythms trip over each other, the spectrum is filled and we become engrossed in an enveloping hive of glitchy sounds. Parts of the system are laid bare before us, and we find ourselves half following glimpses of processes that are set in motion, half enthralled in the density of what is occurring. Finally, we emerge from the cloud, and stagger in a haze in its resonant dregs which slowly filter out until the end.

We shall begin by learning more about Roma’s practice and his dual status on the FluCoMa project as an engineer and a musician. Then we shall explore the workings of this piece, how it was developed and how it works, before looking at how he approaches performing with this system.

Engineer or Artist?

All of the commissioned artists on the FluCoMa project navigate the concept of carrying-out many different activities, notably software engineering and coding, and making music. Indeed, the FluCoMa toolkit is primarily aimed at creative coders who necessarily navigate these two roles, and chances are that you the reader also have experience in this particular dynamic. The nature of much contemporary art is often multidisciplinary and artists nowadays rarely content themselves with a single practice. This was particularly true for Roma who was not only one of the primary engineers behind the FluCoMa tools, but who also came to the project with a strong and developed musical project.

Roma has been live-coding – mainly with SuperCollider – for a long time. In the video above we see an example of a performance he did in 2020 under one of his stage aliases 0001. Here we hear the kind of musical world that he enjoys. He explained that he is “a punk noise musician, I’m always interested in the glitches and failures of technology”. He will often manipulate field recordings, tending to record them himself as he describes himself as “a control freak […] I want to craft the sound of what I’m doing”. In the example above, we also see Roma’s taste for bespoke interfaces, and we understand that this is an important part of his practice. He will tend to remain out of the spotlight, but his software interface will be displayed to all. Indeed, he explained that openness of the interface was an important part of live-coding for him. Unlike many other live-coders who will often keep things as plain text files, Roma seems to craft the interface he engages with (and that the audience sees) very carefully: he curates the snippets of code that we shall be presented with.

Roma turned to music technology to augment his musical practice. As a software engineer, he has always ended to operate in the audio and DSP world. As he explained in his initial artist presentation that can be viewed above at the first FluCoMa plenary, he has worked on projects like Freesound as a software engineer and operated at a very high-level making tools in a variety of contexts. As an engineer, he explained that one needs to approach bugs and glitches as something to be (understandably) avoided. Indeed, his role on the FluCoMa project meant that he had to deliver a set of stable tools to a large group of users, and evidently there is no space for bugs in this context.

He explained that this is a fundamental tension that underpins and drives his practice: in his creative work he strives to find glitches, to push technology to its limits and failure; in his work as an engineer, he must ensure that these things do not occur. He explained that it was very stimulating to explore this tension in FluCoMa, and that the influence of the electroacoustic world was great for his practice. In this world, he explained that “this tension is lived much more naturally”.

Alongside these aesthetic concerns are the very practical issues that can arise when balancing these two roles. As can be expected, even when trying to develop the piece in a creative stance, as he explained, “whenever you encounter issues, you’re tempted to go back to developer mode and fix them”. This was quite useful in terms of development as it allowed him to iron out a lot of bugs in the SuperCollider interface, however he did admit that these hiccups were frustrating and would force him to switch mindset.

Data-driven Musical Interface

So how does the system that Roma created for his FluCoMa performance actually work? At its heart is a 2-dimensional sound map that is being projected behind him onto a large screen. This elements takes up a large amount of space in the performance area, and offers itself as the main artefact that Roma will interact with to make sound. It is something that has emerged from a notably FuCoMa-heavy workflow, and was subject to a lengthy process of iteration and development, as Roma explains in his Traces of Fluid Manipulations video below.

The project is a library for SuperCollider that uses many of the FluCoMa tools called FluidCorpusMap. This library was developed by Roma along with Owen Green and Pierre Alexandre Tremblay and was initially the subject of an article for NIME 2019, Adaptive Mapping of Sound Collections for Data-driven Musical Interfaces which can be read here. It has since been developed, as can be read in the 2021 article for Applied Sciences: A General Framework for Visaulization of Sound Collections in Musical Interfaces, written with Anna Xambó, Green and Tremblay. This subsequent publication sees the library transform from a bespoke musical interface to a broader framework that can easily be incorporated into a workflow. It is still being maintained by Roma, and some of the examples that accompany this text will give you an introduction into using it. It is similar to the artefact that can be produced by following the 2-D corpus explorer tutorial, but offers many features for streamlining the process, and making interaction for preforming possible.

As we saw in other articles, such as the one on Alex Harker’s work or Jacob Hart’s work, Roma developed a workflow for corpus exploration that follows the following broad lines:

- Segmentation: chopping the corpus up into small chunks.

- Description: describing these chunks with audio descriptors.

- Dimensionality reduction: crunching the descriptions of these chunks down into 2 dimensions.

- Visualisation: viewing and navigating these chunks in a 2-dimensional space.

This idea has developed over time, from when Roma presented a prototype at the second FluCoMa plenary and his performance Map Mop at the Web Audio Conference 2019 (see below), where the project was strewn over a number of different environments (SuperCollider, Python, JavaScript); to the polished form it had for the performance in Edinburgh as a robust library for SuperCollider. The final result is what Roma calls a sound map, and can be considered a data-driven musical interface. Not only does creative activity occur when engaging with the artefact in a musical way (see the next section), but also when constructing it.

The idea of corpus curation and sound selection is a broad one; Leafcutter John described the process as “curating a sound world”. Roma takes this process to heart by recording the entire corpus of sounds himself. The field recordings that served as the base material for this piece are cooking sounds. Over a period of a few months, he would keep his recorder ready in his kitchen, and “when I heard something new, like, ‘ok, this potato is making a sound I don’t have!’ then I would grab the recorder and record”. He ended up with about 200 recordings of frying, searing, and broiling. He performed an initial manual curation to “get the interesting bits”, then used the FluCoMa tools to further segment these into a collection of about 1000 small chunks.

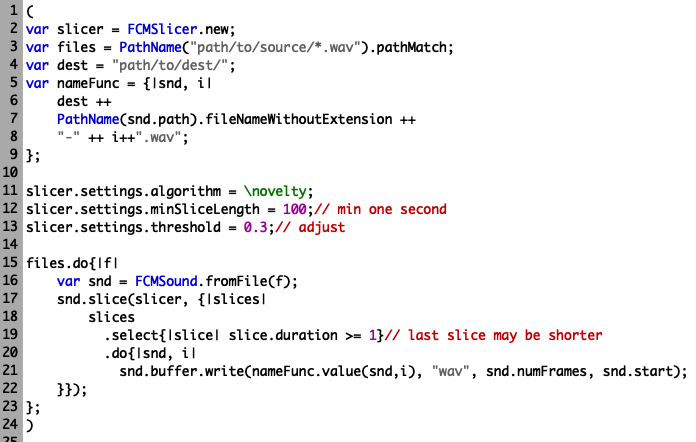

The 01 Audio Slicing example script.

In the example script 01 Audio slicing, we see an example of how Roma achieved this. We see that thanks to Roma’s FluidCorpusMap library, the syntax is very streamlined - he begins by setting a variable called slicer which contains an instance of FCMSlicer. As we see further below, the algorithm setting of this slicer is set to \novelty. Indeed, built on top of the FluCoMa tools, Roma has built a general Slicer class rather than having a distinct class for each slicing algorithm. In the rest of the example we see how batch processing can be performed very quickly.

Once the corpus has been split into chunks, Roma performs description. He uses a host of different audio descriptors, however the most important in terms of constituting the space will be the MFCCs. He explained that “I like things that are noisy, not pitched material” which is why he used this audio descriptor for the distribution of the sounds in space. He then uses UMAP to perform dimensionality reduction and create the mapping. He explains in his Traces of Fluid Manipulations video that high-dimension features like MFCC or chroma are best for this kind of process, however he also uses one-dimensional features such as pitch, spectral centroid and loudness for things like colour, and constituting the waveform we see as the icon.

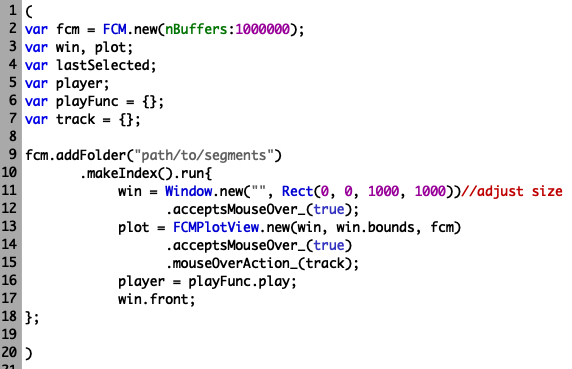

The 02 Creating a Sound Map example script.

In the example script 02 Creating a sound map, we see how this process works. Note that Roma also fits the chunks to a grid using the Jonker-Volgenant algorithm, using oversampling so that the distribution retains some of its shape. In the example script, the player and track functions have been left to blank so that the user may add their own (we see an example of this also in the example script 05 Putting it all Together) Now that we understand how the heart of this system is constructed, let’s now examine how he takes the object and approaches it for performance.

Performing and Live-Coding

There are many ways that one can approach a sound map: Alex Harker uses it as a tool for Computer Aided Composition and assessing the timbral and gestural possibilities of the oboe; Jacob Hart uses it as a tool for musicological analysis, a means of engaging with the score of sonorous potentialities of a musical system. Roma engages with the sound map as an aesthetic object: he uses it as an artefact that will be manipulated and navigated in performance. Let’s see how he does this concretely.

An Akai MIDImix.

Let is recall the disposition of Roma’s performance. He is centre-stage, stat at a small table with a laptop and a small Akai MIDImix controller. He is overshadowed by the massive screen behind him, the listener is clearly invited to lend their attention here. On the screen, we of course see the sound map, however in front of this we also see a simple live-coding interface: two text editors and a slider. Indeed, not only are we shown the sound map and the various agents that will be operating within it, but we also clearly see the commands that Roma is typing to control the system, and are invited to understand some of its workings.

There are eight agents, which are represented as dots of different shades of grey within the sound map. These agents have a position in the space, and follow a trajectory that can be modified and controlled in several different ways:

- Clicking on the sound map to set a fixed position.

- Recording a trajectory through the space with the mouse.

- Controlled programmatically with the left text editor, where the x and y variables correspond to its position.

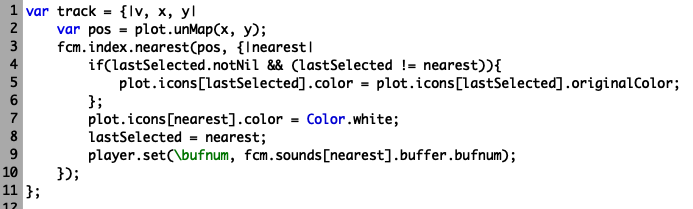

The 03 Navigating the Space example script.

In the example script 03 Navigating the space, we see how we can approach mapping a spot in the space, and how Roma used a kdtree to find the nearest neighbour to the point. This is an example of a function that would be used as the track variable seen in example script 02 Creating a Sound Map. Note that this is a basic interaction that can be performed, consult the FluidCorpusMap repo for more complicated interactions such as the recording of a trajectory within the space.

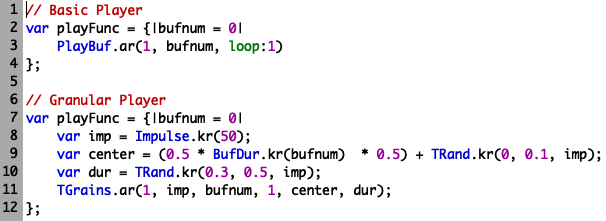

The 04 Playing Sound example script.

Once we have the current nearest neighbour to the agent, there are of course a multitude of things we can do with this information. Essentially, we are pointing to a point in a sound file, and as we see in the example script 04 Playing sound, we can do very basic things such as simply playing back the sound (// Basic Player), or more sophisticated things (// Granular Player). Roma has 4 primary processing modules which he made for the piece that would take the sound and play it back in various ways:

- Chunky: a granulator with characteristically large chunks.

- Bursts: a randomized sample player which is heavily filtered and modulated by an envelope that triggers at random.

- Rumble: a granulator with a delay / feedback effect and a low-pass filter that creates low-frequency ambiance.

- Stir: a randomized sample player with a random on-off gate.

These are being controlled in the left text editor, and we can see the various ways in which they are configured during the performance. The \buf.kr argument that can be seen is the currently selected sound, and the \amp.kr corresponds to the slider. The slider is seen digitally on the screen, but also corresponds to the physical slider on the Akai MIDImix, which means that even when the agent is not active on the screen, Roma can continue to control whatever parameter that slider is currently mapped to.

It is interesting to reflect on the parts of the system that Roma allows us to discover visually during the performance. There is a certain hierarchy in what is presented to us:

- His physical body and computer and controller are present but not necessarily the centre of attention.

- The sound map takes up the whole screen, but is actually behind the live-coding interface and seems to occupy the role of a background where our attention is perhaps only drawn sporadically.

- The live-coding interface, which is on top of everything, where things are constantly happening, where we see exactly how the system is working, yet enough of its workings are hidden for the precise process to remain hidden.

We catch glimpses of evocative function names like chunky, bursts, rumble and stir; and we hear and broadly understand what they seem to be doing, but their actual workings remain hidden. This is true of all processes and performances; however, it is particularly interesting to remark the extent to which Roma chooses to communicate to the audience in a practice that specifically invites the listener to observe and read what is happening.

I addition to this, it is interesting to remember that the interface we are seeing, is also the interface that Roma is seeing – the big screen is a perfect mirror of Roma’s own screen. Entwined within the concerns of what is being seen by the audience, are concerns of how he engages with the system as a performer. This opens up many more questions – for example the functional engagement with the position of points in the space, or why he chooses a certain one-dimensional descriptor to map the colour (spectral centroid), and another to create the icon (loudness). Which of these decisions serve functional purposes, which are more aesthetic? These are all fascinating questions which cross our mind when observing and listening to this performance.

Conclusion

Roma shares with us in this performance a bespoke musical interface that takes questions around live-coding practices to new places. It is also important to note how this sound map interface has inspired others to create and use in their own ways. This kind of artefact has of course been seen before with things like IRCAM’s CataRT, however there are key differences here that open up wide avenues of creative possibilities, notably dimensionality reduction techniques, and the way in which the visual aspect of the artefact (such as the icons) is mapped to other audio descriptors. This is a truly data-driven musical interface that offers an exciting object not only to performers, but to anyone operating in the audio world.