Levels of Translation

In this article we take a look at Ted Moore’s piece quartet, performed by himself and the Switch~ Ensemble, which makes uses of a variety of FluCoMa workflows.

Ted Moore

Introduction

Download the demonstration scripts for this article here.

Today we’ll be taking a look at some of Ted Moore’s creative work, notably with an in-depth look at his piece quartet. Moore joined the FluCoMa project in 2021 as a Research Fellow, and has a long history of using technology and machine learning in his practice. The piece features performances from members of the Switch~ Ensemble: Megan Arns on Percussion, T.J. Borden on Cello, Zach Sheets on Flute and Wei-Han Wu on Piano. The piece makes use of a number of FluCoMa workflows that we shall explore below, and notably presents several approaches to the idea of translation in corpus manipulation. As with all the ”Explore” articles, there is a series of demonstration scripts that can be downloaded and interacted with if you wish to explore the inner workings of the software.

quartet is divided into several quite distinct sections. The first begins with an immediate impact, the four musicians play simultaneously and merge with invisible electronic sounds. Gestures swell smoothly into each other, until suddenly we catch a glimpse of some kind of glitch. At first, we take it for a trick of the eye, but soon we realise that the video is fluidly changing speeds in both directions to accompany the gestural and visceral nature of the sounds. The second section presents a very different setup: quiet sonic ecosystems, built up with mosaicking of short excepts are interjected with full-screen, raucous punctuations. This gives way into a third section which commences with a cello playing alone, making noises that are certainly not those we would expect. Emerging from some uncanny valley, they don’t seem too far removed from the gestures the instrumentalist is making, but they are ultimately completely alien. The cello is soon joined by the four other instruments in similar configurations.

Section four calls back to the first: however, this time, the playback of the audio and video is much more intensely glitched and warped. The gestural nature of the music is emerging from the manipulation of this playback itself, and we are enticed by the musicians’ bodies and movements which take on horrific and unnatural properties. This hijacking of these four musicians continues into a long fifth section, which sees their playing being jitterily smeared across several minutes. Their playing seems to have been segmented, and crammed into an overarching gesture, leaving us astonished and unsettled. Finally, this falls into a last section similar to sections one and four. In this coda, things really seem to decompose, and the long, swelling gestures of the start have fallen into chaos.

We shall begin by taking a look at how the piece came into being, and what is happening under the hood in each of the various sections. We shall examine why and how Moore approaches the question of translation in his work using the FluCoMa tools. We shall also take a look at how Moore uses video in this audio-visual piece. Note that Moore has also documented some of this work in his PhD research Human and Artificial Intelligence Alignment: AI as Musical Assistant and Collaborator.

Musical Translations

Moore presented this piece at Royal Northern College of Music’s Unsupervised Conference 3 in June 2022, and for this he made a version of the piece that offers some annotations explaining what is happening in each section. In sections 1, 2 and 3 we see explicit examples of three different approaches to musical translations. Let’s take a look at each.

Chapters

- Section One (0:0)

- Section Two (1:33)

- Section Three (2:39)

- Section Four (3:51)

- Section Five (6:53)

- Section Six (9:23)

In Section 1, Moore explains that “the source material for the work is a corpus of eurorack synthesizer recordings that have been transcribed by ear for the acoustic instrumentalists to perform”. Aside from composition, a large part of Moore’s practice is live performance electronic improvisation, be it on laptop or eurorack. He has collaborated with many artists, as can be heard in his 2020 album bruit (listen below) which features the likes of Jeanna Lyle, Ben Roidl-Ward, Yung-Tuan Ku and more.

Moore began work on this piece by constructing a tape part from excerpts of various eurorack improvisation recordings he had. “It wasn’t like a one-take improvisation, it was an edited and constructed tape part”. Moore curated the parts he wanted to use and carefully arranged them into a tape. Note that this is a process that Moore performed manually: he explained that “there are some parts of the process that I’m not interested in automating”. He explained that this and the final arrangements are parts of the process he did not automate, as “aesthetic judgement at those parts is key. That’s where I see a lot of the musicality being injected and really originating from”.

In this first step of simultaneous corpus curation and creation, he purposefully created different and varied material: “one is a gestural fast section which opens the piece, and another is very static and sustained”. He wanted to have diversity for the subsequent musical translations to come. This kind of approach to corpus collection and curation is also explored by James Bradbury in his work, although to other ends. Once he has made the tape part, he transcribes it by ear into score form (see below). It is again interesting to note that this is not a process that he looks to automate (we could, for example, imagine using a process similar to AudioGuide’s bach.roll exportation to aid with this). He carefully edits the tape so that the rhythmic subdivisions may make sense to human musicians. Have a listen to the tape part above, and follow the instrumental score below at the same time.

He additionally gave each of the musicians a set of instructions to record a number of ad hoc sounds with their instruments. These were used notably for some of the other sections of the piece. However, in the first section, we get a good look at this idea of literal translations from the electronic tape part to the acoustic instruments. The result is an intriguing passage where the origin of sounds becomes ambiguous. He explained that “one of the really interesting things to me is that there are these moments [where] our brains associate the gesture with the timbre, and there’s a bit of confusion about the source that it’s actually coming from. Even as we’re listening, there’s a crossfade that happens, either literally or in our minds: we’re hearing violin sounds and then seconds later we’re hearing electronic sounds and somehow those are similar enough that the handoff gets confused and ambiguous”.

In addition to these ideas of confusion and ambiguity, Moore explained that translation from his electronic improvisatory performance practice to acoustic instrument composition allows him to transcribe the “musicality and expressivity” in the gestures that come naturally to him in improvisation into his compositional practice. He has explored this idea on several occasions (see above), and it seems to have become a core part of his compositional practice. In this piece however, he looked to take these ideas further.

Machine Translations

In Sections Two and Three, we see two more instances of ways of translating sounds, the first again in the direction of electronic to acoustic instruments, and in the second the opposite. In Section Two, Moore explains that he uses K-nearest neighbour lookup to perform concatenative synthesis: “eurorack synthesizer interjections are used as the target for concatenative synthesis (by means of K-nearest neighbour lookup), combining clips of acoustic instruments to try and recreate the synthesizer’s timbre and gesture”. We see that this comes broadly in the form of two different types of material: quieter passages where different segments of the acoustic instruments are sometimes playing simultaneously, and loud interjections where the acoustic clips quickly succeed each other.

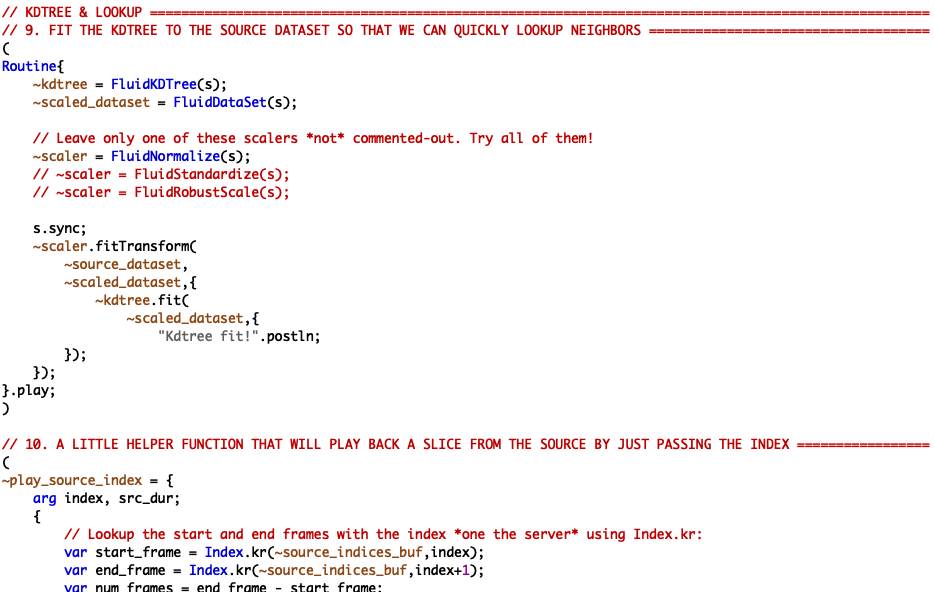

Excerpt of 01 Concatenative Synthesis example script.

In the example script 01 Concatenative Synthesis, we see an overview of how this approach works. There are three main parts:

- Source material analysis.

- Target material analysis.

- Synthesis.

The source and target analyses both happen the same way: after loading the audio, the audio is sliced using the FluidOnsetSlice object, then a dataset is created where each entry is the mean of each MFCC coefficient (with 13 coefficients) using the FluidBufMFCC and FluidBufStats objects. Once the two datasets have been created, we create a KDTree using the FluidKDTree object (after setting a number of different scaling options for the datasets – FluidNormalize, FLuidStandardize or FluidRobustScale), which allows us to perform nearest neighbour searches between the source and target slices. Finally, we can play through the source file, querying the KDTree on each slice, and playing the nearest neighbour in the target dataset.

One large difference in this method with that of simultaneously playing with a transcribed score, is that this type of technique is only really possible in non-real time (although this can be debated, see Rodrigo Constanzo’s C-C-Combine), and it also requires recorded corpora from both sides. These are parameters that Moore was considering from the beginning of the project: “I knew that it was going to be a remote collaboration, that was part of the premise of the project. So I thought, I wonder if there are ways that I could use the FluCoMa toolkit to keep investigating this idea of translation?”. He knew that with this fixed media, remote collaboration dynamic, he was “going to have all this media that I [could] play around with [and see] what sort of affordances that will give me that a live performance would not”.

This is certainly a very different type of translation. The very segmented, jittery nature of onset-driven segmentation concatenative synthesis yields a very different artefact to the continuous and flowing playing of the interpretation of a manually written score that looks to emulate the source. On paper, one could argue that the concatenative synthesis is perhaps infinitely more precise, yet this process leaves a real trace in the sound that leaves no doubt that we are hearing something that has been derived at least in part from some kind of automatic algorithm. Artefacts emerge with a precision that could never be created by a human, yet they emerge in the goal of imitating a human gesture. The result is something particularly uncanny and engaging, driven to new aesthetic places with the inclusion of the video excepts associated with the sound (more on this below).

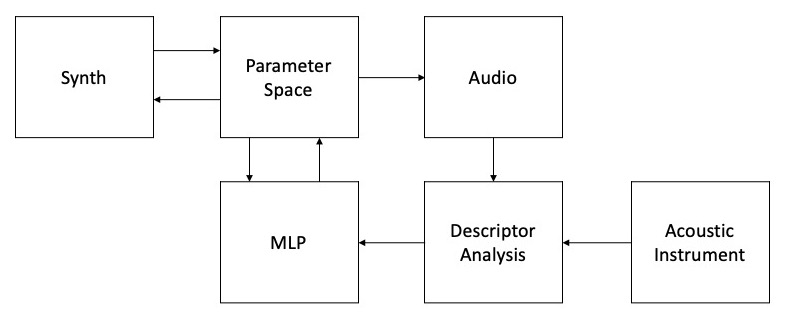

Training/prediction model for Section Three.

In Section Three, Moore explains that “an MLP neural network was trained to predict synthesis of parameters for different synthesis algorithms from audio analyses of those algorithm’s sonic outputs”. For example, Moore trained an MLP to control an FM synthesizer in a way that will try and imitate the incoming audio. Moore talks about this training process in detail in his research, essentially, he follows the following steps:

- Create a dataset of audio that represents the parameter space of the instrument (similar to the iterative FX analysis talked about in the article on Jacob Hart’s musicological use of the tools).

- Perform descriptor audio analysis on each of these datapoints (for example, MFCC analysis).

- Train the MLP using this descriptor data as input, and the parameters that were used to make them as output.

Once he has this model, it means that he can drive the synth parameters with descriptor analysis of any kind of incoming audio – in the case of quartet, a cello, percussion, a flute, or a piano. As you can imagine, and as you can hear in the piece, the result, while not being an exact replica of the input, is an intriguing, uncanny version of the original. Moore describes the result in his research as “[something that] resembles a real-time distortion effect on the input signal”.

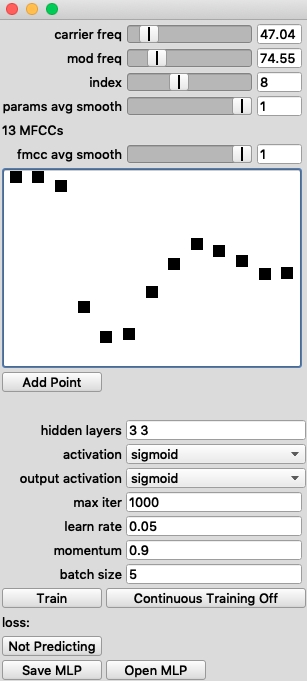

The GUI from example script 02 FM Regression

The example script 02 FM Regression allows us to train a model of this nature. This third iteration of musical translation finds itself flowing in a different direction to the previous two and residing in yet another timescale. Here, depending on how you wish to train the model, it can take a very long time indeed to train the MLP (this simple 3 point parameter space, with 30 steps for the first 2 parameters and 20 for the third, can reach a staggering total of 27000 datapoints), yet the actual translation does occur in real time.

Once again, we obtain something that is not-quite-what it was. We observe that translation, in any form, is inevitably synonymous with filtering of some kind, deformation, loss of resolution. This is something that other people dealing in the FluCoMa realm have thought about, including Darlene Castro Ortiz (listen to her on the FluCoMa Podcast here) who, a bilingual speaker, puts this idea at the heart of her creative practice; and Jacob Hart, who in his musicological research evokes the idea of points of interface in any kind of physical or non-physical network. To transfer an idea, an energy from one realm, from one language, from one system to another, is to lose something, to pervert it in some way. This makes for fascinating listening.

Video

When approaching questions of translation, and translation of meaning across various forms, a powerful aspect to throw into the mix is that of image. Let’s take a look at how Moore is using video in quartet and how it may be contributing to the complicated web of the spectator’s interpretation. Moore uses two primary tools to deal with video: Adobe Premiere and OpenFrameworks. Premier was used to arrange and bring together the rendered video files of the various “experiments” which comprise each section. He describes this as being “another step of the compositional process” and is one of the steps which he chooses not to automate.

The work he did using the C++ creative coding toolkit OpenFrameworks can notably be observed in Sections Four and Six. The annotation that Moore gives here is: “the videos are freely glitched”. Concretely, Moore created an instrument in SuperCollider that would allow him to manipulate the audio part of the videos: “[the instrument] would allow me to play all of the different stems of these performers at the same time and be able to adjust the forward and reverse playback of those stems – so I could perform the audio file as it’s moving through time. I also set up some buttons to do some glitching of the individual performers”. Information would be sent over OSC to OpenFrameworks which dealt with the video and displayed the corresponding frames.

Moore stayed within his native environment of SuperCollider and was able to treat the media in a very performative way. We see him playing with different timescales again – these stems which have been created offline are now the material for real time performance. He explained that “as an improviser, improvising with electronics feels very musical to me very gestural and natural. So any time I can capitalise on that embodied musicality that I’ve developed through my practice, I will. In my compositional process, getting an electronic instrument under my fingers allows me to feel musical and expressive, that’s why I made an instrument like that”. We see that this is another strategy that Moore looks to for injecting the musicality and expressivity that he feels come easier in improvised performance.

He explained that it was important for him to see the effects of his manipulations in real time, as at the end of the day, it is a real time experience for the viewer as well. He gave examples, such as the swinging on the percussionist’s hair which would “swoop in a weird way in reverse” or watching the cellists arm “move up and down the strings really quickly”. It is interesting to consider how these visual fragments have a structural role in the constitution of the piece: like with sound, Moore is attentive to gestures in what he is seeing, and he allows them to play out naturally and structure the piece.

This kind of technique requires some workarounds in order to work effectively, as Moore explained: “most video codecs are essentially made to be played forward at speed 1 – so they really suffer if you try to do something else”. As we see in the piece, the video is moving very fluidly, and sometimes at great speed. To achieve this, Moore converted his video with a HAP video codec – this yields very large video files but allows you to perform very quick lookup of frames. He mentioned that another caveat was that it wasn’t really possible to render anything larger than 1080p – however this was a limitation he was happy to make do with.

A Path Through Sound

Finally, let’s take a look at Section Five, which, as Moore quite rightly assesses, “has a certain weight to it, it feels like an arrival”. Indeed, the section is a lot longer than the others in the piece and seems different in nature. Moore annotates the section in the following way “the machine learning dimensionality reduction algorithm UMAP is used to reorganize the entire corpus of acoustic recordings according to the similarity of their audio analyses.”. How exactly is this working, and how does this develop the idea of musical translations?

The section comes from an interesting set of experiments that Moore performed which gave some intriguing results. He started by slicing his corpus into 100ms segments – this is the first aspect that sets this section apart somewhat from the rest of the piece. Here the slicing of audio is a regular 100ms split, whereas in the case of the concatenative synthesis for example, audio was sliced by onset. Next, he described the data using a whole host of FluCoMa descriptor objects in conjunction with FluidBufStats, giving him over 700 dimensions for each data point.

This is, of course, too much data for a human being to do much with. Following what are now typical FluCoMa workflows, Moore looked to perform dimensionality reduction to gain a better grasp on the data. He crunched these 700 datapoints down to just 11 using PCA – and was still able to retain 99% of the variance of the data. Moore admitted that this meant that “there was probably a lot of noise in the dataset. This was one of my first real workflows with FluCoMa, so I just kind of threw all of the analyses at the wall, thinking I’ll use all of it and see what happens. The good thing about PCA is that it sort of fixes the mistake, or should I say, misguided naivety.”

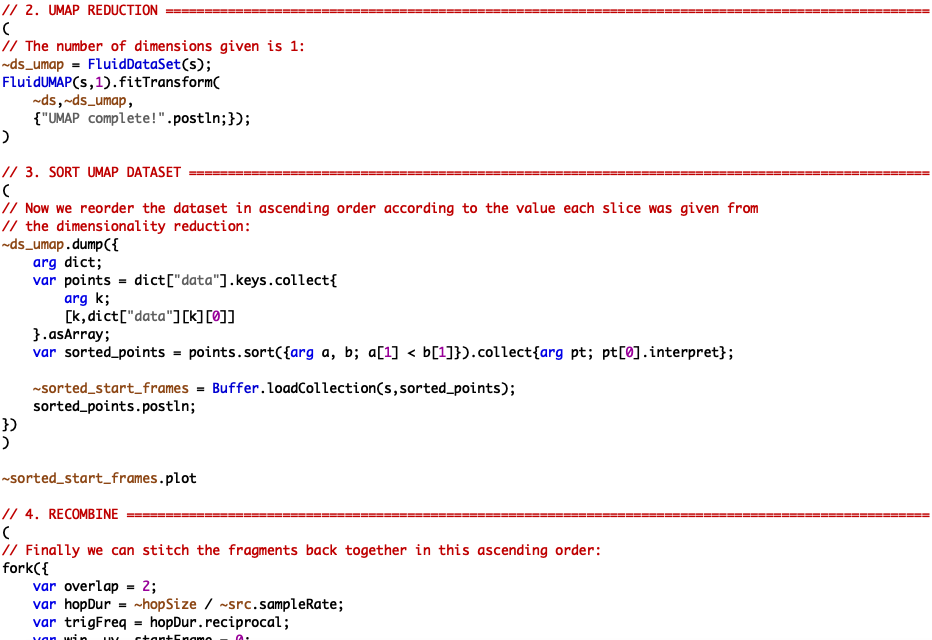

Excerpt of 03 UMAP 1D example script.

Next, Moore wished to forge a path through this space. To do this, he tried two methods that yielded different results. First, he used the FluidUMAP object which is typically used for dimensionality reduction down to 2 or 3 dimensions for visualisation – here however he crunched his dataset down to 1 dimension, essentially looking to place things that were similar to each other, next to each other: this can be experimented with in the example script 03 UMAP 1D (see above). Below we see and hear the results of this experiment. On the left we see the video playback of the current slices being played, and on the right we can see a sound plot, similar to those created by Alex Harker for his CAC, Gerard Roma for his live coding performance or Jacob Hart for his musicological analysis which has been derived from dimensionality reduction.

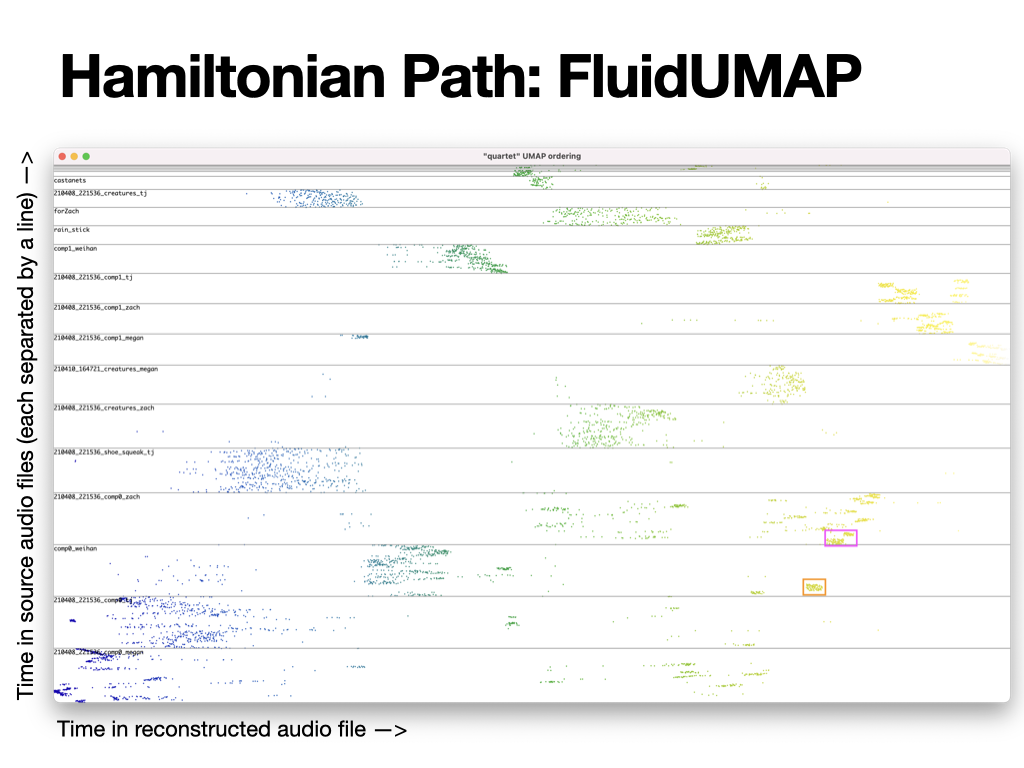

On the sound map we progressively see the path that is being taken through the 11-dimensional space. Broadly, we remark that each cluster gets filled one after the other, and we hear sonically a very definite progression between different sonic morphologies. We can take a look at the image below which shows the results in graph form: along the x axis we have the time in the reconstructed audio file, and along the y axis we have the time in each of the source audio files. We see that segments from a same audio file will tend to group together, confirming the idea that sounds that are similar have been grouped together.

Graph results of the UMAP method.

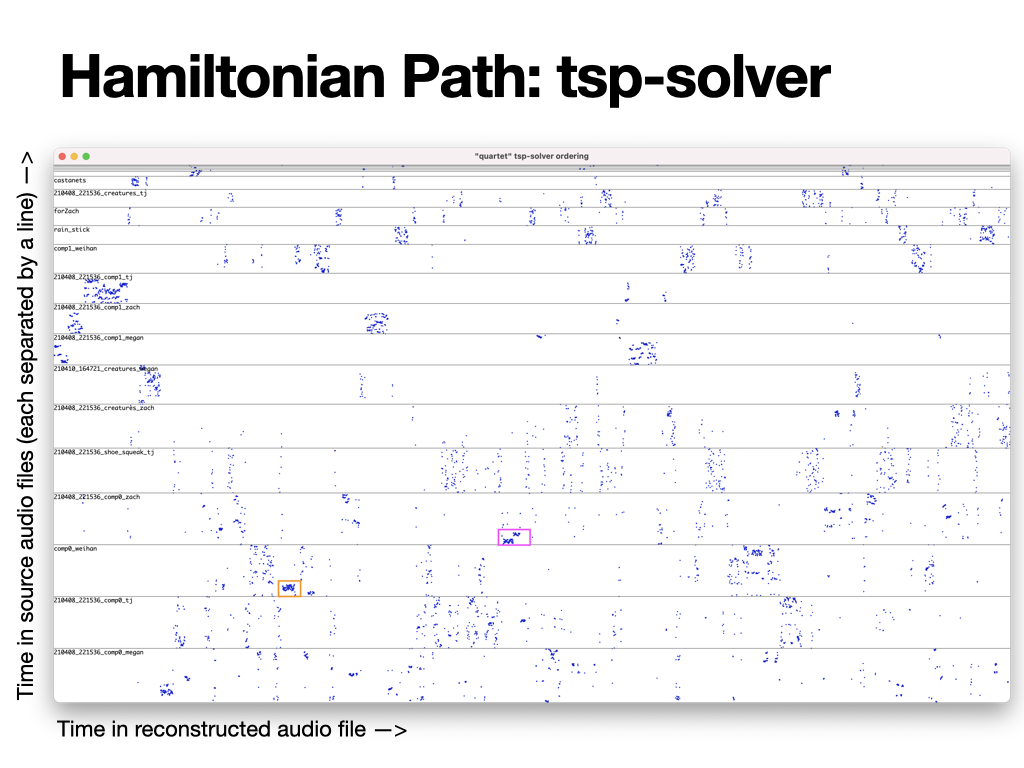

The second method he tried was a travelling salesperson algorithm. The same video format results and graph results can be found below. We immediately notice that the path taken through the 2-diemnsional space is much more sporadic than the UMAP 1D reduction. Remember, this shortest path is being derived through the 11-diemsnional space, so it is unsurprising that there are disparities between the results we get and what we may expect from a 2 dimensional space. In the graph, we see that once again, files from a same audio file do tend to group together, however they are much more split up.

Graph results of the travelling salesperson method.

Moore explained that he did prefer the sonic result of the UMAP algorithm: “there’s more of a gradient crossfade between the different sound files […] however the TSP was interesting because the UMAP crossfades sound like crossfades: but when we listen to music, it’s not all just crossfades. Music has distinct jumps and gestures that move quickly between different timbres, and so in some ways, the TSP ended up, perhaps not more musical, but with more gesturally recognisable moments”.

In the final piece, Moore used a combination of moments from both of these experiments. He identified phrases, sections and gestures that he liked, then reorganized them to create the final version. We see once again the partition between algorithmic generation of material, and aesthetic judgement in arrangement and curation. This passage takes us perhaps the furthest from the initial source and meaning: elements have passed through so many levels of translation that there is no hope of deciphering what the original gesture was. However, the very material of what we hear is there – it remains engrained within the sound. It has passed through a host of filters and systems and has been rearranged into a completely new set of gestures.

The origins and location of meaning seem to be fluid in this context. There are times where sonic signification and aesthetic intent are derived from gesture, yet this can slip and crumble, gesture being transfigured into grain, built up once more into gesture, and it becomes unclear what is at the origin of what, what is talking, what is matter, what is form.

Conclusion

Moore has taken his practice of musical translation to a much deeper level with these experiments using the FluCoMa tools. One aspect that is quite remarkable is, despite the relative novelty of these techniques, Moore still presents a certain maturity in their deployment, always coming back to his composer’s ear for the final decisions, and not letting himself be bound to the algorithm which at the end of the day is but another tool in his arsenal. It is a fascinating piece that is brimming with ideas. One cannot help but be excited to see how these techniques and ideas of translation will be developed in Moore’s future work.