Event Detection and Improvisation

In this article we explore Lauren Sarah Hayes' work using some of the FluCoMa tools for her piece Moon via Spirit. We examine how she incorporated some of the slicing tools into her improvisational practice, and how they can provide different approaches to event detection.

Lauren Sarah Hayes

Introduction

Download the demonstration patches for this article here.

Today we’ll be looking at some of the work that Lauren Sarah Hayes did using the FluCoMa tools. We’ll be taking a broad perspective on some of the working principles of the project and examine how some of its suggested workflows are incorporated into Hayes’ already well-developed improvisational practice. We’ll start by considering her piece for the project and discussing some of her ideas about improvisation. Then, we’ll have a look at the way in which Hayes used the tools within this framework. As with all the ”Explore” articles, there is a series of demonstration patches that can be downloaded and interacted with if you wish to explore the inner workings of the software.

Hayes’ piece, Moon via Spirit, was commissioned by the FluCoMa project and performed at the first FluCoMa gig at HCMF 2019. Her piece was particularly performative in nature: Hayes stood center-stage under a direct spotlight, and her facial expressions and entranced gestures walk us through the music. She is surrounded by a whole host of external hardware: an Elektron Digitakt, a Moog DFAM, an ES-3 module, a TC-Helicon VoiceLive 2, a Korg Nanocontrol, a CME XKey, and of course a laptop which is running her performance patch. As the piece progresses, we get the impression that all these elements are interlinked: Hayes is engulfed within a complicated, resonating, sonorous system. She also holds in her hands a game controller that is being used to control various parts of the music. This is often tilted towards the audience, revealing the way in which delicate gestures have large repercussions on what is being heard.

Moon via Spirit begins with a long section of thick pulsar synthesis, to which Hayes begins to add vocal utterances which are looped and manipulated. She describes this moment as “moving around with the gamepad to find different timbres and textures”. She explains that “there should be a fluidity about how it moves through the whole thing”; she uses different strategies in order to “blend the transitions”. After roughly 4 minutes, the pulsar synthesis fades away, and we enter a more chaotic section filled with drum machine beats and sampled vocals that are recycled and played back in various ways. Towards the end elements progressively filter out, finishing with a series of synthetic glissandi and a few remnant vocal bursts before drawing to a close.

Hayes’ Improvisational Practice

Hayes came to the project with an experience of over a decade in performance, improvisation, and instrument design. The highly synthetic, sung and warped-pop music we hear in Moon via Spirit is but one aspect of her practice. She has also done much work with augmented piano setups (listen below) and haptic feedback which all bear traces in her work for the project. One constant that can be found in most of her work is improvisation with an instrument or interconnected system of instruments that she has created.

The Sweet Spot

When talking about the instrument that she wishes to build and improvise with, she offers the idea of a sweet spot. She describes this as “knowing what’s in the code and having some idea of how she would take a pass through it”, but to still have space for moments of unexpectedness, of surprise: “otherwise there’s no struggle through it as an improviser”. The idea of struggle and resistance is something that she explores in much of her work; finding a balance between having a system which one may guide to do certain things, but to have to struggle with this system in some way in performance and improvisation.

This goes against some broader ideas around improvisation and the notion of flow: in her 2019 article Beyond Skill Acquisition, she examines the idea of flow, proposing that it may have been mystified and reified. She would like to get rid of some of the tropes of flow in improvisation, proposed by the Dreyfus model based around the idea of mindlessness. Hayes nuances this, explaining that she is in fact “very mindful, very aware of things”. She’s not “completely lost in it […] there is expertise and skill, there is a state of flow where gestures and sounds would move in a harmonious direction, but at the same time, [she] is very aware of the fragility”. We add to the ideas of struggle and resistance that of fragility.

This is an aesthetic idea around which Hayes builds her systems. In the context of augmented piano and especially haptic feedback, the idea of resistance can be envisioned quite literally through physical processes that the musician will encounter. However, how does she achieve this in a setup such as the one seen in Moon via Spirit? This can be explored in two main ways: physically and conceptually.

To address the idea physically, Hayes configures the gamepad in a particular way. She cited the work of one of her PhD supervisors, Martin Parker, who discusses working with joysticks and the way in which they are so easy to move and reach their extremities. Hayes creates tension in the system by taking this notion and coupling it with very crude scaling, meaning that the performer must hold the object incredibly still if they wish to freeze a moment. The slightest movement has drastic effects on the whole. She even describes sometimes having to hold a position with her mouth to keep the system in a frozen state. It is indeed through the opposite of physical resistance that she inserts tension and struggle into the system.

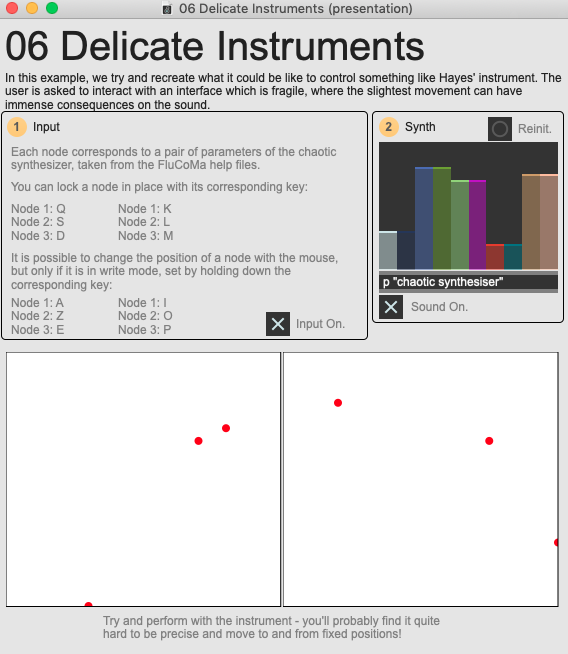

An overview of the '06 Delicate Instruments' example patch, trying to simulate what it may be like to try and play with such a system.

Conceptually, resistance in the system is found inscribed in the way in which her performance patch is coded. We shall investigate this in more detail below, but on a first listen we hear that lots of slicing and automatic triggering of events are happening. Hayes explains that “when you slice stuff, you have no idea which slices are going to come out […] you don’t know how loud or aggressive it might be, or maybe nothing comes out when you expect it to”. She explains that these are moments that she enjoys and are a constitutive part of what she wishes to express as an improviser.

The Moment

Another important aspect to understand about Hayes’ practice is that it is to be considered much more in terms of performance, and the moment. She explains that “it’s not about the whole patch or instrument, but the situation, the audience”. She explained that with so much experience as an improviser, she has gained the confidence so that “even if half the patch were to go wrong, [she] could still give a compelling performance”. This is why radio has “always been troubling for [her]”. She doesn’t push to release records (despite having published several albums to critical acclaim) as she is always concerned about the translation of her work from a live setting to the context of a recording. At the time of the project, she explained that she wasn’t necessarily against the idea, but it is something that she hasn’t explored in great detail (for a great example of Hayes’ recorded work, you can give her latest 2021 SUPERPANG release Embrace a listen below).

She went on to compare some of her work with that of some of the other artists on the project. For example, she said that she found Rodrigo Constanzo or Pierre Alexandre Tremblay’s ways of crafting the sound spectrum to be beautiful, but that it just wasn’t something that she did. This is why during setup she handed her gamepad to someone else and went out into the space to hear what things sounded like. She made the decision to add extra loudspeakers around the space as she wanted to achieve a very “full and enveloping aesthetic” (contrary to some of her piano work where the loudspeakers should be localized to the instrument). These are decisions that she makes in situ, following her ears and what they are hearing in the context of the specific space.

When approaching Hayes’ practice, it is important to understand all of this, and to regard the way in which she forges an instrument in a much broader sense. For example, where some may conceive of the fluid.hpss~ object in terms of its algorithmic properties and its specific ways of decomposing the sound spectrum, Hayes will take this element and describe it as a filter. With her long experience in creative coding, Hayes is aware of the results that different kinds of algorithms yield, and she deploys specific algorithms for specific tasks. These tasks fit into a wide conceptual system and contribute to its functioning – however, to reduce this system to the assemblage of its various parts would be to miss an important aspect for her practice. As we go on to explore how Hayes used some of the FluCoMa tools, we shall bear this in mind. This perspective and the interrogation of the objects she used, and indeed did not use, shall give us insight on her larger aesthetic project.

FluCoMa Tools

One of the overarching possibilities that the FluCoMa toolbox offers, one of its underlying workflows, is the idea of using audio descriptor data to control other things. In the projects composed by the commissioned composers, this can be seen through two primary uses: feature matching (for example in Constanzo’s piece, using descriptor data to query a database of other pieces of audio and finding similar sounds to trigger); and conversion of this descriptor data as control data (for example in Alice Eldridge and Chris Kiefer’s piece, feeding MFCC data into a neural network to be used as control data).

Hayes did experiment with this idea. With 3 months left before the performance, she decided to abandon this avenue, stating that “to have a system that’s so much guided by descriptors for improvisation is super risky, I didn’t have enough time to do that, it could take years”. She explained that it was an ideal, but that she “had a piece to do”. This then begs the question, in the case of Moon via Spirit, what is it that is guiding the system? We shall see that in terms of the code, it is event detection in various forms which is explored most. However, I believe that which guides the system in this case is mostly Hayes herself. A great deal of agency is distributed to the Korg MIDI controller and most importantly her gamepad. Hayes is the primary actor in guiding the system in as much as her gestures on the gamepad and Korg effect the parameters of the system in a very direct way. Indeed, we can imagine that this is a useful configuration if one wishes to insert notions of struggle and resistance into the system.

Event Detection

There are many objects in the FluCoMa toolbox for automatically detecting the beginning of sounds, for slicing audio. This is an important part of Hayes’ software: she explains that this stems from her previous work with augmented piano. Some parts of her patch are recycled from these projects, and it even drives much of the vocal material that she provides for the piece. Lots of the extended singing techniques she deploys have the same sonic profile of a piano note: a sharp pronounced attack followed by resonance. Much of her patch involves the detection of these attacks to trigger events: how does she approach this?

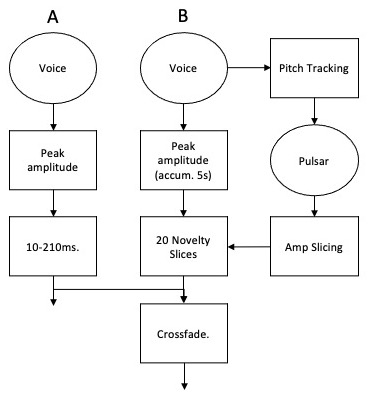

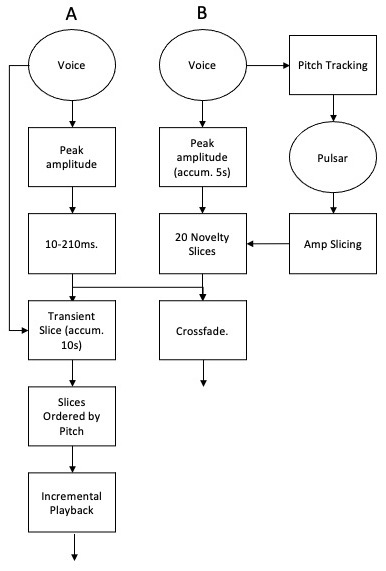

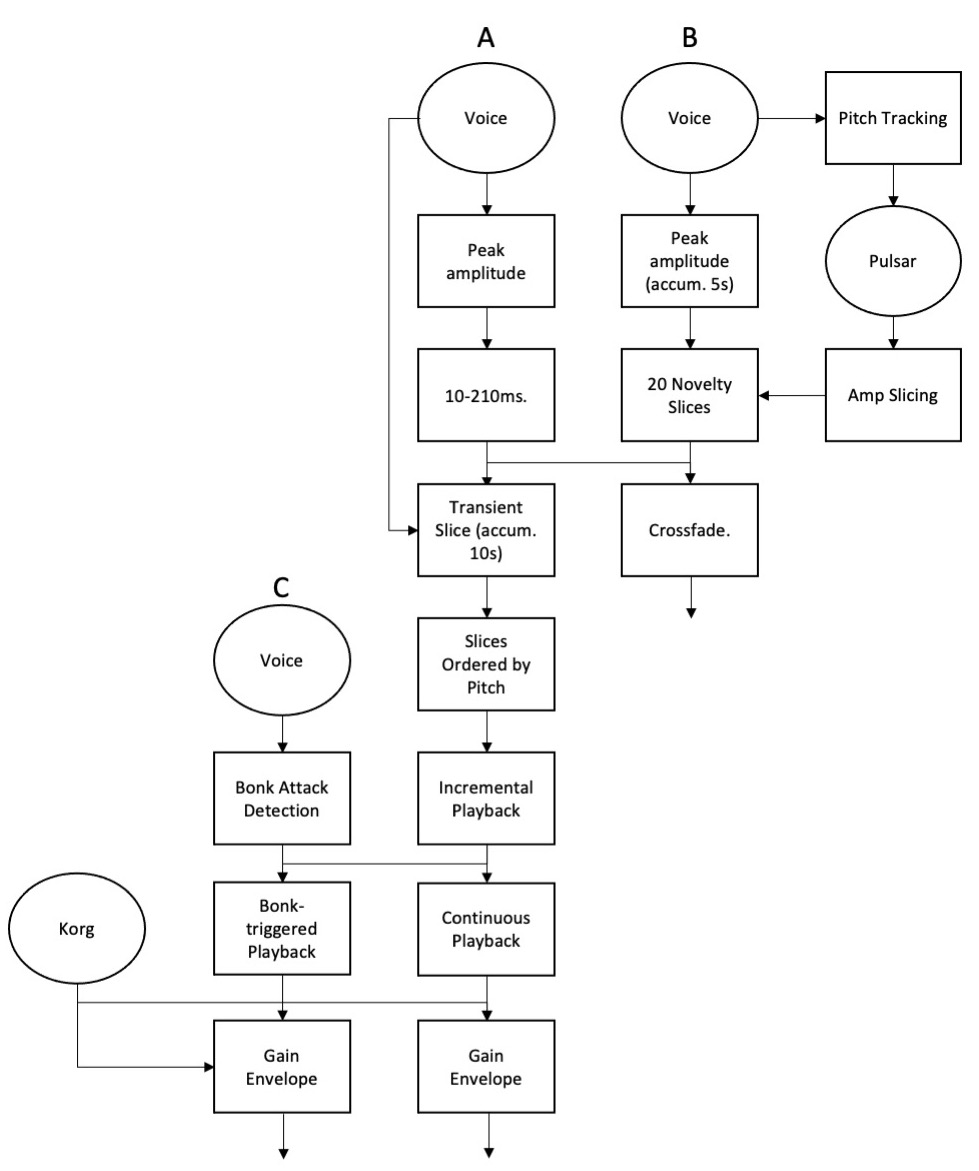

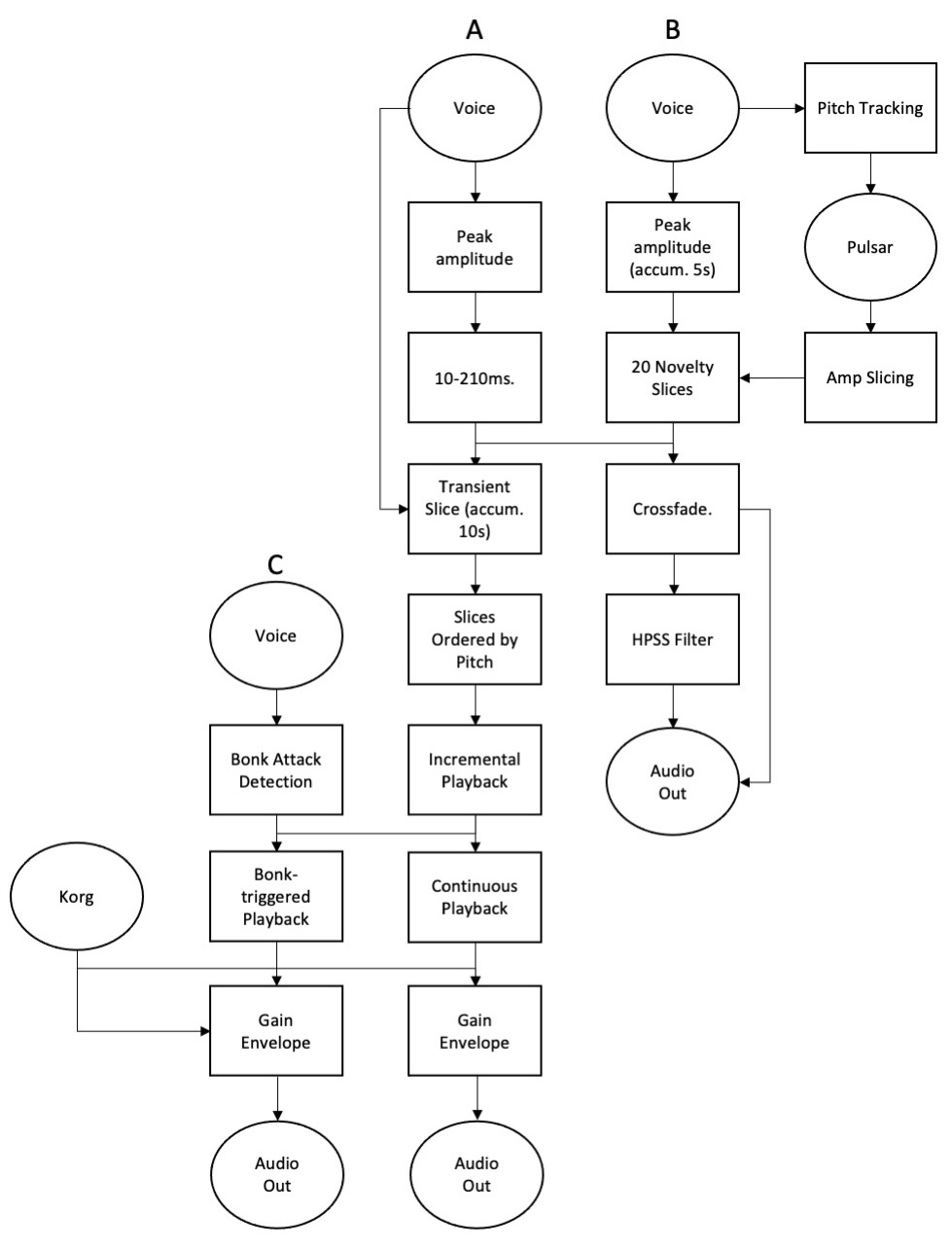

Interestingly, Hayes uses various forms of event detection, indicating to us that she conceives of different types of attacks in different ways. We can try to decipher these conceptions by looking at the code. In the image of her physical setup on stage, the various signal paths in the software are intertwined in a fairly complicated way; to make things easier we can look at this broad representation of what is happening in the patch.

An overview of some of the processing and event detection in Hayes' software.

From this diagram, we immediately remark two important elements:

- A symbiosis between the input of Hayes’ vocals and the input from the pulsar synthesis.

- Different types of audio slicing happening at different points in the signal path.

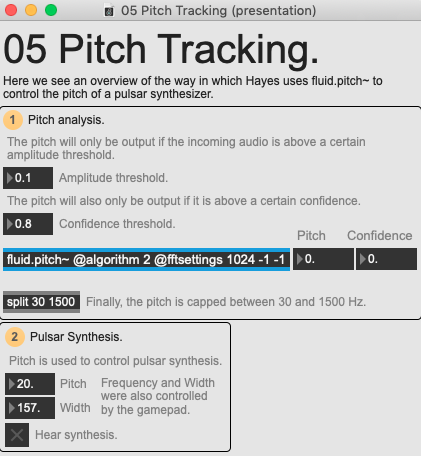

Let’s break this down. Starting with the symbiosis, we remark that the vocals have an immediate effect on the pulsar synthesis. Pitch tracking of the voice, which can be seen in the example patch 05 Pitch Tracking, is controlling the pitch of the pulsar synthesis. There are two immediately performative elements in the piece: the gestures of the gamepad and Hayes’ vocals. Hayes controls parameters of the pulsar synthesis with the gamepad, transcribing performative gestures into this element. However, analysis of the pulsar synthesis also controls some of the ways in which the vocals are processed, creating a conceptual feedback loop between the two performative aspects giving them a complicated and symbiotic relationship.

An overview of the '05 Pitch Tracking' example patch.

The amplitude slicing of the pulsar synthesis (which as we saw is controlled in part by Hayes’ vocals), is used to trigger various things in the patch, notably the playback of slices found in the novelty slicing part of the patch (see below). It is important to understand the relationship between these two important elements, and the extent to which they are interlinked: one cannot exist without the other. This can be heard notably in the first third of the performance (0:00-4:10) where the relationship between these two elements is sonorously explicit.

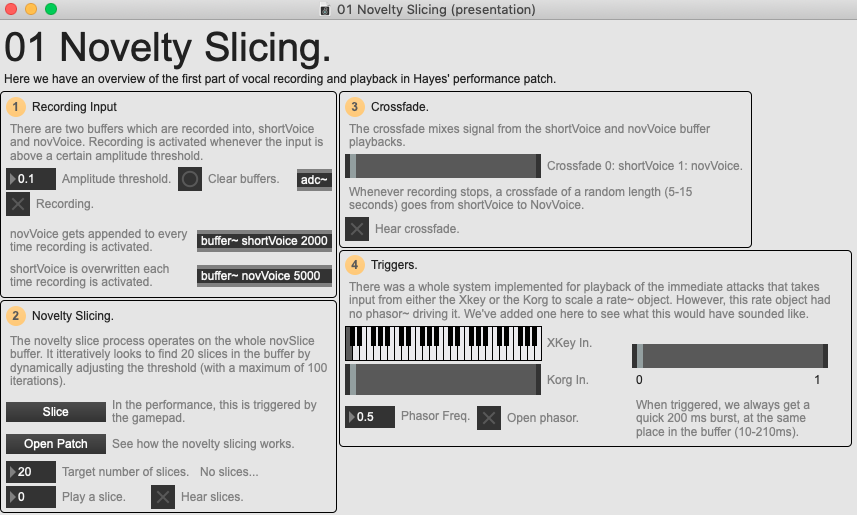

An overview of the '01 Novelty Slicing' example patch.

Let us look at the various audio slicings. The first slicings can be seen in the example patch 01 Novelty Slicing: this groups the Immediate Attacks, Novelty Slicer and Crossfade modules identified in the representation above. What will be interesting to observe is the chain of various slicings, and what they mean for Hayes’ conception of events. First, there is a general amplitude slicing using the Max native peakamp~ object that allows recording into two buffers. One buffer of 2 seconds (shortVoice), and another of 5 seconds (novVoice). The short buffer is overwritten whenever a new recording begins, and the long buffer is appended to. This already gives us one kind of event: the content in the shortVoice buffer is some kind of object unto itself. We shall bear this in mind for later.

Using the gamepad, Hayes can trigger processing on the contents of the novVoice buffer. This runs an iterative novelty slicing patch, which seeks to find 20 slices within the 5 second recording. These will then be kept and will be randomly triggered by the amp slicing we shall see below. Signals are then crossfaded whenever recording into the buffers ends from shortVoice to novVoice and sent to various parts of the patch. Let’s keep a summary of the various streams of audio, the various events which are derived from the different chains of slicing. For the moment, we have one slicing using peak amplitude (A), and another using novelty slicing (B).

A representation of the signal path in Hayes' patch (1).

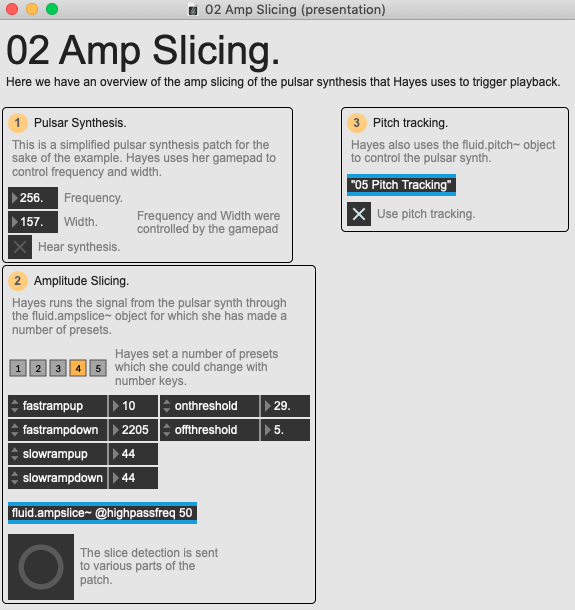

An overview of the '02 Amp Slicing' example patch.

Next, we can add to this the amp slicing, which can be explored in the 02 Amp Slicing example patch. The pulsar synthesizer runs through the fluid.ampslice~ object, and the detected slicings are used to trigger the playback of one of the novelty slice segments. The pitch of the pulsar synthesis can also be controlled by pitch tracking of the vocal input. If we update our signal chain, we see that we have the same final objects, but B has been developed. Note that the amplitude slicing also triggers other things in the patch.

A representation of the signal path in Hayes' patch (2).

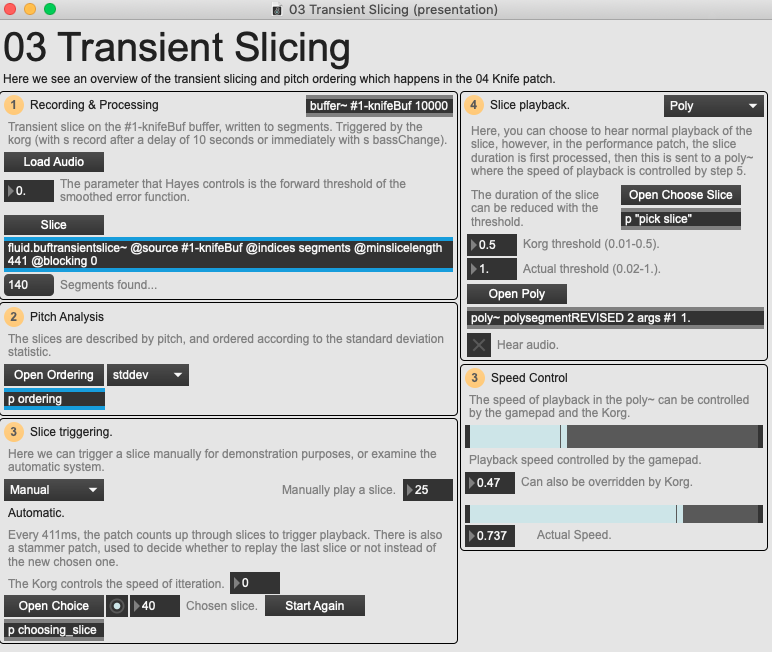

After this, we can add the slicing that occurs within the 04 Knife example patch. This begins with transient slicing and pitch ordering which can be viewed in the 03 Transient Slicing example patch. As we see on the broad representation of the code above, the audio coming into this is from the Immediate Attacks playback, or audio stream A, but also straight from the main voice input. As we see on the screenshot of the example patch below, this audio is recorded into a buffer of 10 seconds whenever Hayes triggers the process with the Korg.

An overview of the '03 Transient Slicing' example patch.

Once recording is finished, the analysis of this recorded audio begins: Hayes first slices the audio using fluid.buftransientslice~. The parameters of this slicer are fixed, except for the forward threshold which is controlled by the Korg (on a scaling of 0-127 to 0.01-2.). Once the slices have been found they are analyzed using the fluid.bufpitch~ object, and then ordered according to the standard deviation statistic (found using fluid.bufstats~). The slices are played back incrementally, sometimes repeating, and the speed of triggering and playback are controlled by the Korg. This playback is sent into the 04 Knife example patch which we shall explore below.

One interesting aspect to note is that here, the main controlling object for the processing and playback is the Korg. Note that the Korg is a very different object to the gamepad: during the performance it was on a flight case, not constantly in Hayes’ grasp; and, unlike the gamepad, it is something that can retain its state without supervision (once a certain slider is set to a value, this value will not change). It is interesting to remark which parts of the software Hayes decides to control with which objects.

A representation of the signal path in Hayes' patch (3).

We can now update our signal flow representation again. Note that we still only have two different signal paths: the transients slicing and pitch analysis has been added on to the end of path A. The voice also directly goes into the transient slicing process. It could be argued that this created a new signal path in itself, however as the signals are mixed together and treated together, we have decided to conceive of this as one path. It is, however, important to remember that this is a somewhat subjective representation of what is happening, and in such a sprawling and interconnected piece of software such as this, other interpretations could be entirely possible.

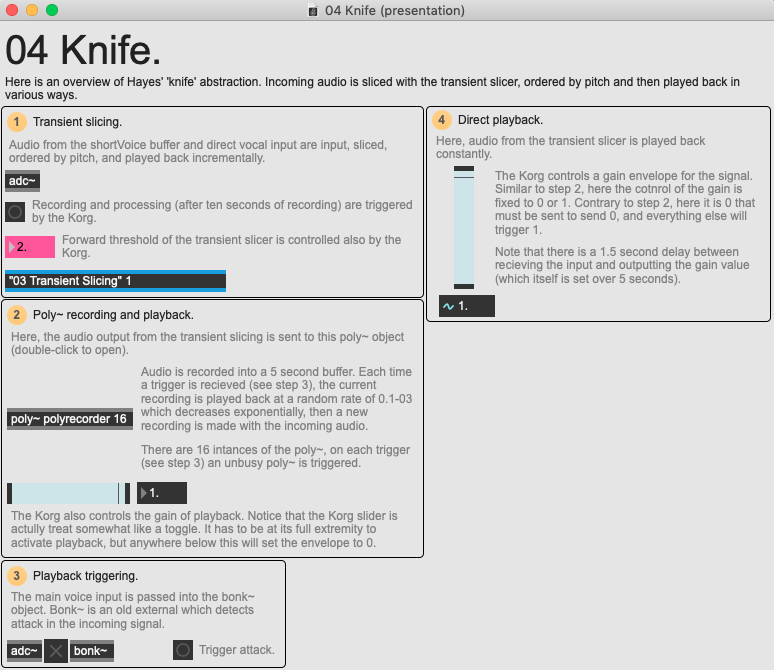

An overview of the '04 Knife' example patch.

Now let us look at the 04 Knife example patch. As discussed above, this starts with the transient slicing process. The audio that comes out of the transient slicing patch is sent to two places:

- The first (seen in step 4 of the example image) is constantly playing back the audio. The gain of this is being controlled by the Korg controller.

- The second (seen in steps 2 and 3) takes the audio and passes it to a poly~ object. When triggered this records a 5 second slice of the audio which will be played back on the next trigger at a slow rate (0.1-0.3). The gain of this is also controlled by the Korg. Triggering is controlled by the bonk~ object, an old object developed by Miller Puckette that detects attacks in the incoming signal (this could also be achieved with the FluCoMa tools).

One interesting aspect to note in this part of the software, and in others, is the way in which control signals are treated. First, we observe here in step 2 that the Korg’s input will always trigger either 0 or 1 - if the slider is at its maximum, we output 1, anything below the maximum outputs 0. In step 4, the opposite happens, anything above the minimum outputs 1, and only the minimum will output 0. This can inform us about the way in which Hayes engages with the controller, perhaps forcing herself to perform extreme gestures to trigger certain events.

A second aspect is that of delayed output. For example, here we observe that in step 4, the setting of the gain level will be delayed by 1.5 seconds, and then the change interpolates over a space of 5 seconds. This second interpolation time can be attributed to wanting to avoid sharp cuts, however the initial delay of the command is particularly interesting. Similarly, when recording and processing of the transient slicer is triggered by the Korg, we observe a 7 second delay after which the forward threshold is set to 2. If we consider this in the context of struggle and resistance, we can imagine that coding this latency into the actionning of control data will create a situation where the improviser must operate decisions in a broader timescale, thinking back and forward about what their actions may cause.

A representation of the signal path in Hayes' patch (4).

Finally, we can once more update our representation of the signal paths. Here, we see that a new path has been added (C). Once again, we could conceivably represent this differently as both outputs are routed together. The reason we have defined two signal paths is that the gain of the outputs of the two playback methods are controlled separately, leading us to believe that the two signals are not only distinct in terms of sound, but also in terms of gesture.

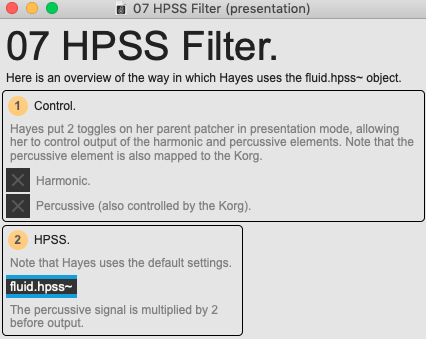

An overview of the '07 HPSS Filer' example patch.

Finally we can look at the HPSS Filter part of the main representation. This can be viewed in the 07 HPSS Filter example patch. As you can see, this is a somewhat out-of-the-box usage of the fluid.hpss~ object, with the exception that Hayes doubles the gain of the percussive output. It is also interesting to note that Hayes allowed control of the output of both signals from the parent patcher in presentation mode via toggles, but only mapped control of the percussive element to the Korg.

A representation of the signal path in Hayes' patch (5).

We can finally update our signal paths in the following way. We see that the HPSS Filter has been added to signal path B, taking the output from the crossfade between the novelty slicing and immediate attack of the voice. There is also a bypass of the HPSS Filter as the signal is also directed straight out. The outputs of paths A and C have also been sent to Audio Outs: note that the gain levels for all of these outputs are present on the parent patcher in presentation mode, and also mapped to be controlled by Korg. Before output Hayes also applied various filters to the sound, the parameters of which are also controlled by the Korg.

Event Interpretation

This leaves us with 3 distinct yet interconnected signal paths. They all begin with the voice, they can all be considered as merging into one another at some point, and they all share common objects for control (the gamepad and the Korg controller). As we have seen, they each explore different kinds of event detection, but how can we read these signal paths in terms of what these events could actually mean to Hayes in performance? How could we read these paths in terms of what things like novelty slicing and transient slicing mean for a creative coder such as Hayes?

Let’s begin by looking at the beginnings of signal paths A and B. The voice is first sliced using the peakamp~ object. With this first slicing, there is no notion of onset or transient: as long as the incoming audio is above a certain amplitude, the sound will be recorded for processing. Compare this with the top of signal path C which uses the bonk~ object. Here Hayes is specifically looking for attacks in her voice. This is because these two parts of the patch have very different functions:

- With peakamp~, Hayes is recording material for further use - her criteria for recording is essentially the presence of sound.

- With bonk~, Hayes is triggering the playback of material, meaning that there is some link between an attack in the voice and the sound that shall be played by the patch.

We see an interesting symbiosis of these two functions also at the top of signal path B. Here, the pitch tracking of Hayes’ voice is used to control the pitch of the pulsar synth - this can be considered as a continuous production of material. However the pulsar synth is then sliced by amplitude using the fluid.ampslice~ tool. Notice the use of fluid.ampslice~ here and not bonk~. This could suggest that the events that Hayes is looking to detect here are not so much attacks as they are notable differences in the pulsar signal. This is interesting as the events detected will be used to trigger slices derived from a novelty slicing.

Let us look at the novelty slicing in more detail. The source is an accumulation over 5 seconds of input from the peakamp~ collected material. The feature is the Spectrum, and Hayes iteratively looks to find 20 slices. This suggests a certain stability in this part of the patch: to a certain extent, Hayes can expect a certain output. This also brings back a notion discussed earlier - that of latency in events. Here, Hayes has the possibility of somewhat directly triggering playback of the novelty slicing, however it will trigger events that were recorded previously. It is interesting to wonder the extent to which Hayes will prepare certain events in advance while improvising. This highlights some of the challenges which come with improvising with such a system.

Indeed, the further we go down the signal paths, the more this notion is amplified. The transient slicing in signal path A operates on a 10 second buffer of accumulated audio, itself being derived from a previous accumulation of audio. These slices will be ordered by pitch in an iterative manner, continuously in path A and on attacks in path C. It seems that the configuration of the transient slicing and the pitch ordering will allow Hayes to take this accumulated audio and shape it into some kind of form that will of course never be the same over different performances, but morphologically somewhat recurrent: as series of transient attack which play out in an upward pitch progression. This is something that Hayes also approaches in another form in other parts of the patch which we haven’t looked at, using NMF activations to match the morphologies of sounds.

Finally, it is interesting to remark the output of signal path B, and its either direct output or output through the HPSS Filter. There is a certain idea of onset, as the crossfade jumps back to the immediate attack signal on each recording into the shortVoice buffer, but then fades back into a more continuous playback of novelty slices triggered by amplitude detection in the pulsar synth. The percussive element of the HPSS Filter is doubled in gain, and is also controlled directly by the Korg, suggesting that Hayes looked to exploit the percussive part of these sounds more than the harmonic.

Before concluding, one final aspect to note is that it is important not to allow the signal path representation to sway our understanding of the instrument in the wrong direction. Indeed, it must be remembered that, notably at audio output, Hayes still has a great deal of control over the gain of these signals. These aren’t continuous signals that we hear all of the time, the performer can again operate slicings and create events and gestures through their control with objects like the gamepad and the Korg. It is, however, a useful tool for breaking down some of the ideas in the patch, and to begin to understand how Hayes may conceive of event detection in her practice.

Conclusion

Of course, what we have seen here today is but one part of an enormously complex, interconnected and intricate instrument/improvisation system. To understand this system fully, not only is it necessary to perform a much wider analytical sweep of the entirety of its elements, but also to experience it in motion: as explained at the beginning of this article, the context of the moment within which it is deployed is an essential part of this system. Hayes is an improviser - she builds a system which will provide not just control over the sound, but also moments of surprise, notions of resistance, of struggle. Here, we saw how Hayes incorporated some of the FluCoMa tools into this system, and how they can be levied to provide these kinds of things.